When it comes to fitness training, it is sometimes difficult to find a female-specific topic because the same principles and practices apply to both women and men. Nevertheless, there are other gender-specific issues, and one important one that was discussed recently in the Journal of Sport Rehabilitation is the fact that women are more likely to suffer knee injuries. And, most seriously, women have a greater risk of suffering a non-contact anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear. An ACL tear is one of the most serious injuries in sport, normally requiring surgery and a long period of rehabilitation. A non-contact tear occurs without impact with another person or object ('ACL injuries in the female athlete', Journal of Sports Rehabilitation, 6, pp 97-110, 1997).

How a non-contact ACL tear occurs

The anterior cruciate ligament is one of four knee ligaments that join the femur to the tibia (thigh bone and shin bone). Specifically, the ACL attaches to the front (anterior) portion of the top of the tibia and runs diagonally up, attaching to the rear of the bottom of the femur. Its main function is to hold the knee stable during leg movements and to prevent hyperextension of the knee joint.

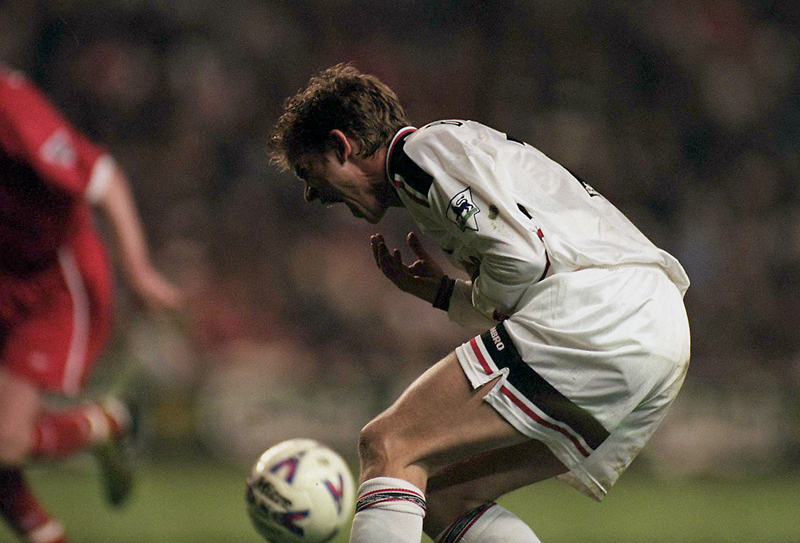

A non-contact ACL tear always involves a rapid deceleration of the knee joint. This can happen during a landing from a jump, or during a leg plant in a cutting movement (side-step). Athletes must be capable of performing a controlled and stable rapid deceleration of the knee in all directions, forwards, diagonal and sideways. Sometimes the knee is not stable during a rapid deceleration owing to forces from the hip and ankle placing the knee in a weak position. This is when a non-contact ACL tear can occur.

The ACL is most vulnerable when the knee is pointing inwards and the foot is pointing outwards with the torso falling forwards. Therefore, one common position that can lead to an ACL tear is when the knee is fixed around 20 degrees of flexion, almost straight, the torso is leaning forward, the thigh is internally rotated, shin externally rotated and the foot is pronated. The quadriceps and hamstrings are attempting to control the deceleration of the knee, but the position places overload on the ACL.

Why women more than men?

There are a number of anatomical and physiological differences between men and women which may account for the increased ACL tear risk that women bear. These differences biomechanically predispose women to having the knee internally rotated; thus they are more likely to find themselves in the vulnerable ACL position.

Women have a wider pelvis which leads to a greater Q angle of the femur. This means the femur angles inward from hip to knee, which leads to greater internal rotation forces of the knee joint and an internally facing patella (knee-cap). Women have less muscular development, especially in the vastus medialis oblique, which plays a crucial role in patella alignment. Women have greater knee flexibility, which may decrease joint stability. They also have a smaller intercondylar notch which impinges the ACL, thus placing it under greater tensile stress. Finally, women have increased foot pronation, which also places internal rotation forces on the knee.

It is clear that due to a collection of anatomical differences the female athlete will have increased internal rotation of the knee. These, together with the physiological differences which potentially lead to less strength and decreased joint stability, mean the female athlete is at much greater risk of ACL injury than the male.. Interestingly, the same differences also lead to greater knee internal rotation when running and explain why women athletes are commonly prone to anterior knee pain, or runner's knee.

How to prevent ACL injuries

Hip weakness can exacerbate the anatomical alignment problems. Additional internal rotation of the knee can occur too far and too fast if the hip abductors and hip external rotators are not functional. The static pelvic position has been shown to influence the rate of ACL injury. Weak lower abdominals and poor muscular control can lead to a forward pelvic tilt, or sway-back position. This forward pelvic tilt also allows more internal rotation than happens when the pelvis is held in neutral alignment. Strengthening the body core muscles, gluteus medius, external hip rotators, lower abdominals and obliques should increase stability and help control knee internal rotation, thus reducing ACL injury risks.

Strong quadriceps and hamstrings are also crucial for ACL injury prevention. Women are considered to be more ligament-dominant in stabilising the knee joint, whereas men are more muscle-dominant. Thus, it is essential that the quadriceps are strengthened so they are capable of eccentrically controlling rapid knee joint decelerations.

However, overtraining the quadriceps compared to hamstrings is detrimental, since the hamstrings must cooperate with the quads during knee joint decelerations to assist the stabilising role of the ACL. It has been shown that athletes with good hamstring/quadriceps strength ratios suffer fewer non-contact ACL injuries. Strong ankle and calf muscles also help control the knee joint decelerations and help provide more stability from the ankle.

Along with good all-round leg, hip and trunk strength, the coordination of the muscular recruitment is important for knee injury prevention. Neuromuscular coordination must occur optimally for the knee joint to be safely controlled. Thus coordination drills and proprioceptive training are equally as important as muscular strength training in preventing ACL injury. Sporting movements are very rapid. Landing and cutting movements involve little knee flexion movement but require large deceleration forces. Thus the hamstrings need to fire quickly on impact as the knee joint is decelerated, and this must be properly coordinated with a strong eccentric contraction from the quadriceps. In addition, the hip and ankle muscles must be active so that hip and ankle stability is maintained. For effective ACL injury prevention training, knee deceleration movements such as landing, cutting, hopping, etc., must be included as separate drills.

Teaching the correct techniques of these movements can also help prevent injury. The landing movement should involve an upright torso position, and increased knee flexion on impact should be encouraged. In addition, continuing to move after landing also helps because less deceleration is required. Unfortunately, in sports such as gymnastics, basketball and netball, this is not always possible. The cutting movement should be performed by lowering one's centre of gravity and increasing knee flexion. This allows for more stability and a more powerful quadriceps contraction. Trying to cut with a straight leg is ineffective as well as dangerous. Encouraging a less severe cut also helps, although again this is not always possible since it is a less effective movement.

Finally, using the correct footwear is essential. The athlete's shoes should always be stable to control any excess pronation. Prescribed orthotics may also help with this. The grip must always be suitable for the surface on which the game is being played. Gripping and not slipping is essential for ACL injury prevention.

In summary

Women suffer more non-contact ACL tears than men. This is because of anatomical and physiological differences that predispose women to having internal rotation forces at the knee which makes them more vulnerable to ACL tears during landing and cutting movements. In addition, women are not as strong as men, which potentially leads to less control of the knee and more internal rotation.

To help prevent injuries, women athletes should make sure they are strong in the quadriceps, hamstrings, hip abductors, hip external rotators, abdominals and obliques. The neuromuscular coordination of the knee joint deceleration movement should be trained with landing, cutting and hopping drills. The correct techniques for landing and cutting should be practised and the correct shoes should always be worn.

Raphael Brandon