You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Dental health in athletes: why cleanliness is next to godliness

Alicia Filley looks at worrying research on dental health in athletes, and provides guidance for those who want keep their teeth into old age…

Athletes are notorious for their bad mouths. No, not the kind that need to be washed out with soap, but the kind that lack regular dental and oral care. After the 2012 London Olympics, it transpired that no less than 30% of the medical consultations were for dental issues(1). Sports professionals then realised that were no longer able ignore the gaping need for oral health intervention in this population.

How bad is the problem? Sports and dental practitioners in the UK conducted a systematic literature review and found poor oral health in athletes that participate in a wide range of sports, from both developed and underdeveloped countries, and at the most elite levels(1). Indeed, the oral health was so bad in the studies sited, the authors concluded that elite athletes were no better than many disadvantaged populations in keeping their mouths healthy.

Talking out of both sides of their mouths

In a population so fixated on health and performance excellence, how do athletes wind up with such poor dentition? One explanation may be that poor oral health is an inherent risk of being an athlete. Endurance athletes typically ingest a diet high in carbohydrates (CHO). The sports drinks, supplements, gels and gummies that an athlete consumes while training bathe the teeth in CHO. An athlete may not brush his teeth for several hours after training, thus giving the CHO time to settle in and feed dental decay. In addition, a diet high in CHO may contribute to systemic inflammation, thus increasing the chances of periodontal disease.

Another risk factor from athletic activity is dehydration and dry mouth. Saliva can be thought of as Nature’s toothbrush, acting to remove food and microbes, and helping to re-mineralise the teeth. Dehydration from sport or a dry mouth from mouth breathing during exertion, makes the teeth more vulnerable to cavities from CHO and erosion from acidic foods and drinks, and the gums more vulnerable to bacterial attack.

Researchers from the University of Birmingham have also suggested that training itself may increase the risk of poor oral health. They subjected 10 well-trained male cyclists to nine days of intensified training and monitored its effect on salivary free light chains (FLCs)(2). They used the salivary FLCs, a component of immunoglobulin, as an indicator of the amount of oral inflammation. After the period of intense training, the cyclists demonstrated an increase in salivary FLCs but not in the number of FLCs found in the blood. This finding seems to indicate that high intensity training increases oral inflammation, which contributes to issues such as periodontal disease and possibly lowers overall oral immunity. This study was quite small and these findings need further exploration, but it should make athletes sit up and increase attention to their teeth when they increase their training load.

Sinking their teeth in

Researchers from University College London dove deeper into the oral health issue, to determine what effect it had on psychosocial factors, training participation, performance outcomes, and overall health(3). They examined and assessed the oral health of 279 Olympic and professional athletes from nine different sporting fields. They then administered a questionnaire to each athlete and evaluated their overall health, quality of life, and participation in sport.

Nearly half of the athletes had current or treated cavities. A total of 41.4% of the athletes showed evidence of erosive tooth wear. The researchers found more evidence of tooth erosion in males than females; in mixed sports than endurance sports; and in football than sailing. The screened athletes demonstrated particularly low levels of gum health. Over 77% of these athletes experienced bleeding on tooth pocket depth probing (see figure 1 and watch the process here). Bleeding indicates the presence of gum disease, which, if unchecked, can eventually lead to abscesses and even tooth loss. Other findings included infections around wisdom teeth, pain, sensitivity, and dental injuries from sport.

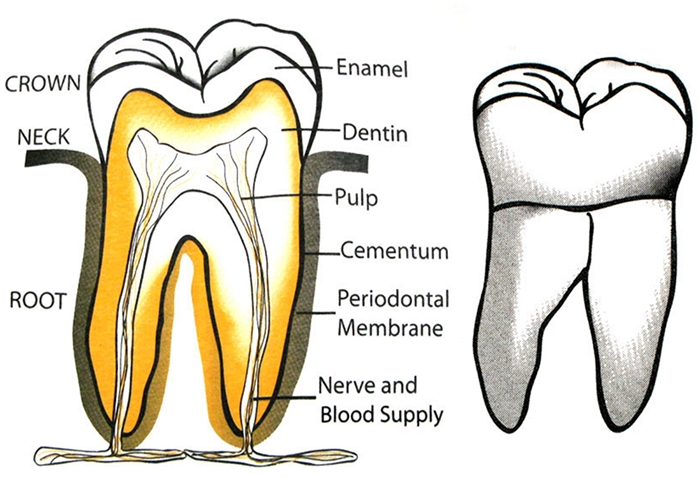

Figure 1: Cross section of a tooth

The visible part above the gum is called the crown. Enamel covers the crown and protects the dentin underneath. Worn down by grinding, clinching, and acidic food and drink, compromised enamel allows decay to form and exposes the dentin, causing pain and sensitivity.

The pulp contains the blood vessels and nerves that feed the tooth. Pockets between the gums and the neck of the tooth that form from food retention allow bacteria to grow and contribute to gingivitis or gum disease. Dentists determine gum health by probing these pockets and measuring their depth. Healthy gums have shallow pockets. The periodontal membrane and the cementum keep the tooth connected to the socket.

Approximately half (49.1%) reported some sort of psychosocial effect from the state of their oral health. Athletes described trouble eating or drinking (34.6%), relaxing or sleeping (15.1%), and smiling. Some (17.2%) stated they felt embarrassed by their oral health, especially when laughing or showing their teeth.

When it came to performance, nearly one-third (32.0%) felt their oral health impacted their overall sporting ability. The areas affected included training and competing, maintaining training volume, and oral pain. Both the physical symptoms of poor oral health and the psychosocial results showed associations with decreased performance. Athletes with dental issues that caused pain, reported difficulties in eating and/or drinking, poorer sleep quality, and showed a tendency toward lower performance or ability to fully participate in training. At an elite level, where champions are made in fractions of a second, poor oral health could keep someone off the podium.

A kick in the teeth

Most endurance activities such as running, swimming, rowing etc carry a low risk of trauma. Cyclists however are at risk of collisions and falls from the bike, but these rarely result in tooth damage. Instead, traumatic tooth damage in sport results primarily from player to player contact, accounting for nearly one third of all dental injuries(4). Oral health may impact healing, but overall, doesn’t play a role in its occurrence. But if you like to play contact sports in addition to your endurance sport, just what factors are most likely to lead to such an injury?

Japanese researchers surveyed 5735 young athletes ages 6-15(4). The boys reported a significantly higher percentage of dental trauma (14.3%) than the girls (10.7%). Surprisingly, age, size, sport, or participation in contact or non-contact sport didn’t play a role in tooth injuries. It turned out that not enough time for breaks during training, verbal abuse, and physical reprimands from coaches were most strongly associated with mouth trauma in the boys. This was the first study to site environmental factors as contributors to dental trauma. Indeed, team culture as dictated by a coach certainly contributes to the aggressiveness of the players. This increased aggressiveness may place players in situations of oral contact more often.

Mouthguard use

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) requires athletes that play field hockey, American football, lacrosse, and ice hockey, to wear mouthguards. Athletes who do not wear mouthguards are almost two times more likely to suffer a traumatic dental injury than those who do wear them(5). An avulsed tooth (one that is forced out of the mouth by impact), can be very expensive and time consuming to manage, making mouthguards a particularly cheap and smart investment! Remember too that tooth trauma also takes away time from sport. Italian researchers studied 30 young athletes with dental injuries(6). Those with strictly tooth damage returned to sport in three to five days. Athletes with injuries that also involved the soft tissue of the gums required up to 14 days of recovery before returning to sport.

Practical recommendations

Without a doubt, being an athlete increases the risk of poor oral health. The bad news is that poor dentition decreases your chances of performing your best. The good news is that dental disaster is entirely preventable! With a little extra attention, an athlete can have a sparkling smile when they cross the finish. Follow these recommendations to improve your oral health and perform at your best:

- Brush teeth with a high strength fluoride toothpaste at least twice per day;

- Floss at least one time per day;

- See a dentist for twice yearly cleaning and check-ups;

- Decrease intake of high CHO drinks and gels;

- If using high CHO foods during training, keep mouth moist and alternate with water;

- To protect dental enamel, reduce use of highly acidic foods and drinks (see panel below)

- Extract third molars (wisdom teeth) if prone to infection;

- Consider using a mouthguard even if not recommended for your sport;

- Frequently clean mouthguard and obtain a new one for each new sport season;

- Pay extra attention to oral hygiene during periods of high intensity training.

Panel: tips for enamel health

- Try to choose sport drinks with the lowest acidity (highest pH - preferably higher than 5.5). This is not easy however because the information on product labels rarely includes any reference to the drink’s pH value.

- Drink larger volumes of sports drink less often rather than sipping (thereby reducing tooth exposure time to sugar and acids).

- Don’t use sports drinks as a mouthwash - swallow the drink immediately, reducing tooth contact time.

- Mix a bit of skimmed milk into your carbohydrate drink (if the taste is acceptable and it doesn’t cause you any gastric distr

- Where possible, drink some skimmed milk after consuming any acidic drinks.

- Use enamel protecting/strengthening toothpaste.

- Visit the dentist regularly; he/she will be able to detect early signs of erosion and advise you accordingly.

References

- Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:3-6

- Physiology and Behavior. 2018;188:181-87

- Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;1-6

- BMC Oral Health. 2017;17:168

- J Athletic Train. 2016;51(10):821-39

- Open Dentistry J. 2018;12:1-10

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.