Athletes: Is your daily diet up to scratch?

Recent evidence continues to suggest that many athletes, especially females, are still struggling to fulfill their basic nutritional needs. Why, and how can athletes avoid the dietary pitfalls?

The last 40 years have seen tremendous advances in the sphere of sport nutrition, particularly when it comes to fueling for and during an event, match or tournament. Indeed, enter “sports nutrition” into any internet search engine and you’ll get a deluge of results from sports supplement companies and retailers offering products such as carbohydrate drinks and gels, protein recovery products and supplements such as creatine and caffeine – all of which are sold on the premise of enhancing sport performance. But while there’s good science supporting the use of many of these products, over-reliance on them has distinct downsides.Performance - not from a bottle

The problem is that many athletes mistakenly believe that high-tech sports nutrition formulations and supplements can guarantee optimum performance, leading to a ‘performance from a bottle’ mentality. Unfortunately however, relying heavily on sports nutrition products may actually lead to a poorer basic diet quality, because many athletes simply assume that they no longer need to worry about eating high quality natural foods, leading to a reduced intake of key nutrients. A poorer, low-nutrient diet is undesirable for a number of reasons – not least because such diets are associated with lowered immunity and a generally reduced resilience of the body to withstand the day in, day out rigors and cumulative stresses of training.Ensuring the day-to-day diet is as nutritious and healthy as possible should be the cornerstone of any long-term nutrition plan, and therefore the number one priority for athletes seeking performance. While sports drinks and supplements have their place – especially when training volumes and intensities increase – an athlete’s day-to-day diet is actually far more important. But hang on, I hear you say – nearly all athletes are aware of the vital role of good nutrition so surely they consume a pretty well sorted day-to-day diet, especially given the abundance of nutritional information freely available online and in other media? You might think this is the case but the reality is far from the truth. It turns out that despite believing their nutrition to be adequate, the diet of many athletes is well below optimum, leading to insufficiencies and deficiencies. Indeed, you might even be one of them!

The evidence for poorly nourished athletes

Over the past two decades or so, a growing body of evidence has accumulated demonstrating that a wide range of sub-elite and elite athletes often fall short of meeting their basic dietary needs. Moreover, the studies reporting these findings keep coming; our growing understanding of the athlete’s nutritional needs and the easy availability of excellent online information and advice does not seem to have improved athletes’ levels of knowledge or diminished findings of nutritional insufficiency in the athletic community. Just a few examples of these findings include:- Elite male swimmers – over 50% of whom were deficient in calcium and insufficient in carbohydrate intake(1).

- Female judo athletes who failed to meet their needs for iron, calcium B1 and niacin intakes(2).

- Female handball, runner, karate and basketball athletes, 100% of whom failed to meet their magnesium and copper intake requirements(3).

- Highly trained female cyclists, whose average daily intakes for folic acid, magnesium, iron, and zinc were sub optimum, while. More than one-third of the cyclists failed to consume even 60% of the recommended daily intake for vitamins B6, B12, E and the minerals magnesium, iron, and zinc(4).

- Seventy two elite female athletes where 65% failed to meet carbohydrate intake recommendations and many failed to meet their needs for for folic acid, calcium, magnesium, and iron(5).

- Over 550 Dutch elite and sub-elite athletes, the majority of whom had sub-optimum vitamin D intakes and where iron intake was sub optimum in a substantial number of the women(6).

Are females more prone to sub-optimum dietary practices?

Although studies suggest that sub-optimum dietary practices are common among both male and female athletes, there’s persuasive evidence that female athletes may be more prone to dietary insufficiency (note the abundance of female athletes featuring in the above examples). A recent review study looked into this topic and concluded that female athletes are indeed more likely to suffer from sub-optimum nutrition(7). The reasons are complex, but the authors concluded that the likely reasons are the different physiology of the female body – for example monthly menses, which increases the risk of iron deficiency – along with other factors such as a desire to reduce body fat levels through increased training loads, and aesthetic reasons (particularly in sports such as gymnastics and swimming where athletes are subject to the pressure of performing in front of large crowds).Who is most prone to sub-optimum nutrition?

Research on athlete nutrition suggests that female swimmers(8) and female gymnasts(9) may be among the highest risk for poor dietary practices in sport (for all the reasons cited above). And now, new research by a team of Slovenian scientists not only provides further evidence of this risk, but has also compared the risk of nutritional deficiencies in the two sports among age and performance-level matched athletes(10).In this study, the researchers examined the nutritional status and cardiovascular health markers of two groups of female athletes (17 swimmers and 17 gymnasts) of the same age and all training and competing at a high level. To do this, the athletes’ body composition measures (lean body mass vs. fat mass) were assessed by bioelectrical impedance while dietary intakes were analyzed using a standardized food frequency questionnaire. Importantly, the athletes also underwent blood testing for nutrient levels (ie to see how and whether the reported dietary intakes correlated with actual nutrient levels) for a number of nutrients including vitamins B12 and D, and the minerals calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, and iron. In addition, the athletes were tested for blood lipids (triglycerides and LDL/HDL cholesterol) and blood pressure, to establish any cardiovascular health implications of the athletes’ nutritional status.

The findings

The main findings were as follows:- Although the two groups of athletes had similar levels of body fat %, the gymnasts had lower fat-free mass than the swimmers (42.4 vs. 46.6kg) indicating the swimmers had more lean muscle mass.

- Both groups had low intake of carbohydrates, fibre, polyunsaturated fats, and high intake of free sugars and saturated fats

- The gymnasts were consuming low levels of protein

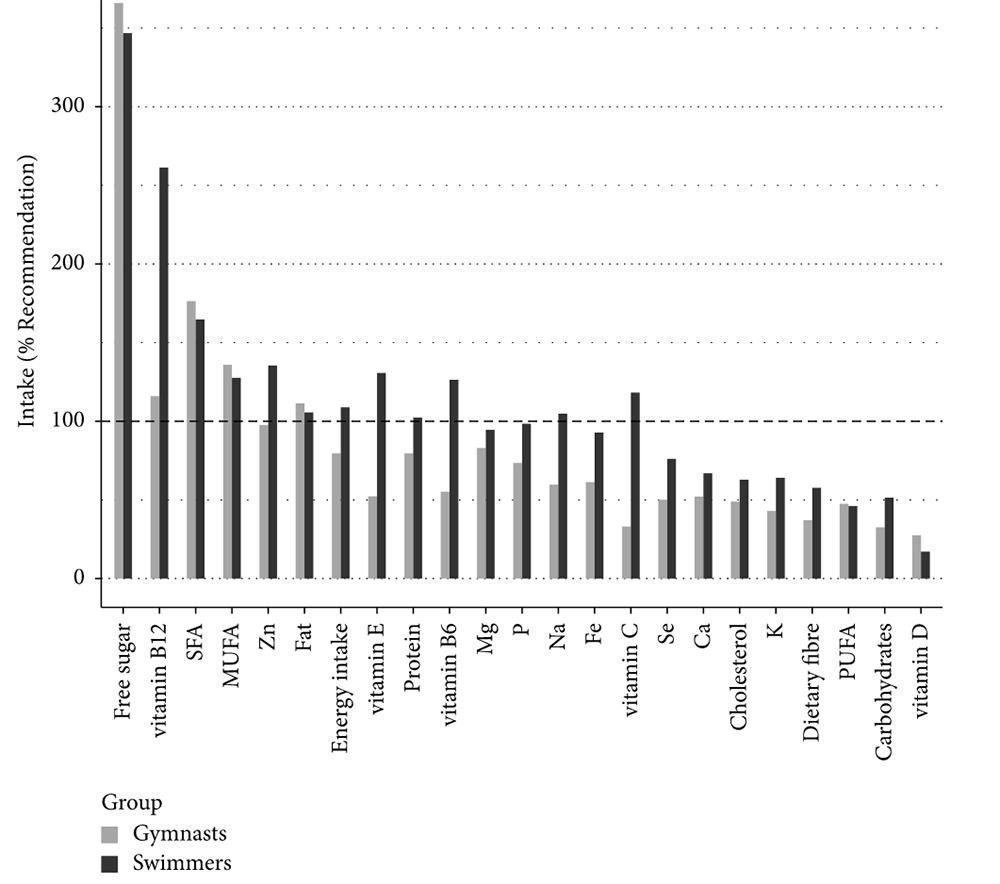

- Both groups were deemed insufficient in micronutrient (vitamin and mineral) levels but the gymnasts much more markedly so (see figure 1).

- Both groups had very significantly lower-than-recommended serum levels of vitamin D3.

Figure 1: Dietary intake of elite-level gymnasts and swimmers(10)

Key: SFA = saturated fatty acids; MUFA = monounsaturated fatty acids; Zn = zinc; Mg = magnesium; P = phosphorous; Na = sodium; Fe = iron; Se = selenium; Ca = calcium; K = potassium; PUFA = polyunsaturated fatty acids. The gymnasts fell significantly short of reaching the recommended intakes of most of the nutrients tested, while the swimmers fell short in many.

The researchers commented that the gymnasts had lower intake of energy and all macro- and micronutrients compared to swimmers, but more importantly, dietary patterns BOTH athlete groups had ample room for improvement. Breaking the results down further, the gymnasts had below their recommended energy intake, whereas both gymnasts and swimmers had below recommended intakes of fiber and polyunsaturated fats. In addition, gymnasts had below their recommended intake of protein and 11 out of 13 micronutrients (except vitamin B12 and zinc), whereas swimmers had below recommended intakes of vitamin D, calcium, potassium, and selenium.

Conversely, both groups of athletes consumed 17% of their calories as sugar (both added and contained in foods), exceeding the recommended upper limit of less than 5% of total calorie intake per day(11,12). In summary, they researchers concluded that overall, dietary intake, especially micronutrients, among the participants in their study was ‘sub-optimal’, and that this was likely due to the low total energy intake, especially in gymnasts, and food choices characterized by very low intake of whole grains, beans, fruits, and vegetables and high intake of processed and ultra-processed foods high in sugars, salt, saturated, and trans-fatty acids.

Take home messages for athletes

The message is clear; many athletes, even those training and competing at an elite level, are still not meeting their basic day-to-day dietary needs. This may be particularly true for female athletes. Meanwhile, trying to compensate for a poor diet by consuming sports nutrition products and/or vitamin supplements is no substitute – 59% of the gymnasts and 86% of the swimmers in the above study took both sports nutrition and vitamin/mineral supplements, yet failed to meet their dietary and nutrient needs!Athletes should therefore focus on ensuring their dietary basics are up to scratch before thinking about exotic supplements. A simple 5-step checklist is outlined below, but athletes and coaches are strongly advised to read around the subject and seek professional guidance from a qualified nutrition consultant if needed. This article provides a good overview of how to assess whether athletes are meeting their basic nutritional needs and also provides some essential reading about what constitutes the basics of a high-quality day-to-day diet for an athlete engaged in training and competition.

Five recommendations for day-to-day nutrition

- PLENTY OF FLUIDS – No matter how much you drink during your training or racing, if you start less than fully hydrated as a result of poor dietary habits, you’re going to struggle. You should aim to drink a total (ie from all sources) of around 2-3 litres of fluid per day on non-training days. On training days, this should be increased to accommodate additional fluid losses; as a rule of thumb, if your urine colour is never darker than a pale straw colour, you’re doing okay!

- ADEQUATE AMOUNTS OF CARBOHYDRATE – Unprocessed carbohydrates (starchy foods such as whole grain breads, cereals, pasta, rice, potatoes, beans etc) are your body’s 5-star fuel for training and racing, so (unless you’re training to improve fat burning or lose weight) these foods should form a key part of the diet, especially in the run-up to a race (55-60% of your calorie intake). For an active athlete consuming around 3,000kcals per day, this means 1600-1800kcals of carbohydrate per day, equating to around 400-450g of carbohydrate per day. Obviously however, carbohydrate needs will rise and fall in line with training volumes. Sugars are also a type of carbohydrate but to avoid blood sugar swings and energy dips, sugary carbohydrates are best consumed only sparingly – preferably restricted to during and immediately after exercise, when muscles are best able to absorb carbohydrate rapidly.

- SUFFICIENT PROTEIN – Exercise breaks down muscle tissue so adequate protein is vital for muscle recovery/ repair as well as growth and strength development following training. The best sources of protein are low-saturated fat sources – lean cuts of meat, white fish, skimmed milk and low-fat dairy produce (ie yoghurts and cheeses). Nuts, seeds and oily fish are also good sources of protein because the fats present are mainly the healthy, essential fats (omega-3 and omega-6 fats).

- PLENTY OF FRUITS AND VEGETABLES – Fresh fruits and vegetables are not only excellent sources of vitamins, minerals and fibre, they’re also packed full of protective, health-giving antioxidants – often referred to as ‘phytochemicals’. Recent research suggests that these phytochemicals can help to ward off illness and disease and may even help protect muscles from exercise-induced damage and reduce post-exercise muscle soreness(13).

- SUFFICIENT LEVELS OF MICRONUTRIENTS – Vitamins and minerals are needed to facilitate the tens of thousands of biochemical reactions required to keep your body performing at its peak. All natural, unprocessed foods are rich in these nutrients. By contrast, junk, fatty, processed, refined, sugary foods (and alcohol) contain plenty of calories but little in the way of nutrients, which is why you should try and limit these junk calories to less than 10% of your total calorie intake.

- Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2004 Feb;14(1):81-94

- Nutrition. 2002 Jan;18(1):86-90

- Int J Sport Nutr. 1999 Sep;9(3):295-309

- Am Diet Assoc. 1989 Nov;89(11):1620-3

- Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2010 Jun;20(3):245-56

- Nutrients. 2017 Feb 15;9(2). pii: E142. doi: 10.3390/nu9020142

- Journal of Women's Health 2020; May 13; Vol 29, No. 5

- Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2014 Aug;24(4):450-9

- Eur J Sport Sci. 2016 Sep;16(6):726-35

- J Nutr Metab. 2021 Jan 12;2021:8810548

- Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2017 vol. 65 (6) 681–696, 2017

- assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/445503/SACN_Carbohydrates_and_Health.pdf

- Nutrients. 2019 Oct 7;11(10):2389.

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.