You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Post-exercise recovery: first, do no pharma

Can the post-exercise use of over-the-counter medications such as ibuprofen really help athletes to recover faster? Andrew Sheaff looks at recent evidence and provides essential advice

When it comes to improving performance, most of the focus is on the hard training that is necessary to stimulate progress. However, hard training is only half of the equation; it is the recovery that follows hard training which ultimately results in improved performance. Beyond the value of recovery from a performance perspective, training hard often leaves athletes sore and tired, something understood to be a necessary component of training but avoided whenever possible.

Minimizing downsides

As awareness of the importance of recovery has improved, and considering athletes have always sought to minimize the negative effects of hard training, the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) among athletes has become quite common. These drugs are typically used to treat pain and fever, as both have an inflammatory component. However, as inflammation also occurs both systemically and within the muscle as a result of hard training, athletes sometimes use these drugs to combat the stiffness and soreness that follows challenging workouts.

Beyond symptomatic relief, the thought process is that the sooner pain and inflammation go away, the sooner one can train hard again. And the more often hard training sessions are performed, the faster and more significant the improvements can be made. The problem with this line of thinking is that inflammation is actually a critical part of the adaptive process.

Inflammation and adaptation

While it may be no fun to experience, inflammation and the associated cellular process help rebuild the tissues to be stronger and more resilient. Therefore, removing the inflammation may actually prevent the desired adaptations from occurring. And when you look at the emerging evidence, there’s a consensus that NSAIDs may compromise muscle growth (hypertrophy) when taken chronically – almost certainly as a result of disruption in natural inflammatory processes(1).

Beyond the potential negative impact on muscle hypertrophy, as their name implies, NSAIDs are drugs, and they are not without side effects, particularly for gastric health. When taken for long periods of time, these side effects may become problematic – see this article. Moreover, while the chronic use of NSAIDs may not be a great idea, it’s not even clear if NSAIDs actually have a positive impact in the short-term. Much of the research is mixed, with little consensus for a positive effect of NSAIDs. While it’s assumed that they can speed recovery in the short-term, this hasn’t consistently been demonstrated to be the case. Moreover, it’s not clear if different NSAIDs have different impacts on recovery from exercise, especially when taken prior to exercise.

Considering the prevalence of NSAID use in athletic populations, it’s important to provide clarity as to whether these drugs are actually creating the intended effect. As there are documented long-term consequences to their use, there should be documented short-term benefits to justify taking these drugs to assist with recovery from exercise. With clearer information, athletes can make more informed decisions as to whether to use these drugs.

New research

For more clarity, we can turn to a recent study by a group of researchers from the US Army(2). The researchers compared three different types of NSAIDs: ibuprofen, flurbiprofen, and celecoxib. Ibuprofen is available over the counter, whereas the other two drugs are available via prescription only. Importantly, the research was performed using a ‘placebo-controlled randomized, double-blinded, cross-over study design’. Let’s break that down because it’s important with regard to the validity of the study:

· To compare the impact of the various NSAIDS versus doing nothing at all, a placebo was included where the subject took an inert pill that had no effect at all.

· A cross-over design signifies that all subjects performed each version of the experiment, taking all three NSAIDS as well as the placebo. This ensures that the subjects in each group were the same, eliminating the possibility that the results could be influenced by the selection of the subjects.

· The order in which the various NSAIDS and placebos were taken was randomized as well to ensure that any influence of repeated testing or familiarization of the testing protocol was removed as well.

· Finally, the research was performed in a double-blind fashion in that both the researchers and the subjects were ‘blind’ as to which treatment was happening during each testing session. No one knew which pill the subject was taking. This removed the possibility that the beliefs or expectations of the subjects and the researchers could influence the results of the study.

Overall, the purpose of this methodology was to remove as much bias as possible from the experimental design. As you can see, the experimenters went to great lengths to produce quality research that was less likely to produce misleading data.

What they did

The researchers recruited twelve healthy subjects to take place in the study. Each subject performed the testing battery five times, once for familiarization and once for each of the treatment options. For each round of testing, the subjects ingested one of the treatment pills, two hours before the testing protocols and the plyometric session that was used to create fatigue.

During the familiarization session only, the subjects performed a one-repetition maximum test on the leg press, and this weight was used to calculate the loading to be used during the plyometric session. Prior to performing the plyometric session, the subjects also performed a maximal vertical jump as a measure of power performance. In addition, they performed a maximal voluntary contraction on a modified leg press machine equipped with force plates known as the ‘plyo-press’. While maintaining hip and knee angles of 90 degrees, the subjects pressed as hard as they could into the machine for 5 seconds. The highest recorded force was used.

To induce muscle damage, the subjects performed ten sets of 10 x jumps on the plyo-press machine, using 40% of their 1 repetition max on the machine. The plyo-press machine is basically a leg press on tracks which allows subjects to ‘jump’ by pressing themselves away from the stationary platform. Weight can be added to the sled to increase the load. One jump was performed every second and there was two minutes rest between each set of time.

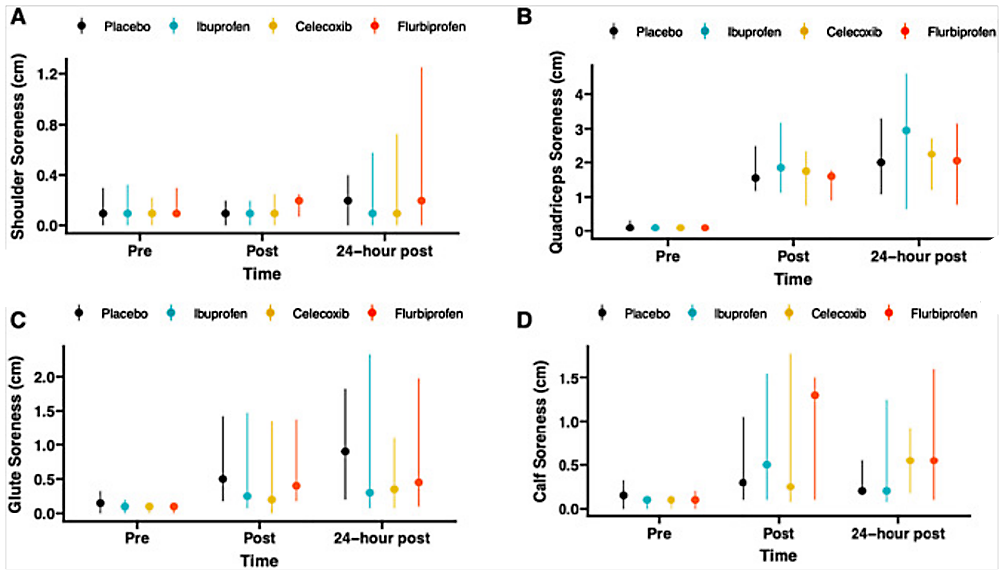

Subjective muscle soreness testing was also undertaken; the subjects were asked to measure the soreness of their shoulder, quadriceps (frontal thigh), gluteus maximus (buttocks), and calves on a scale of 0-10 with ‘0’ representing no soreness and ‘10’ representing maximal soreness. Vertical jump, maximal voluntary contraction, and muscle soreness testing was performed immediately prior to the plyometric exercise, then 4 hours and 24 hours afterwards. This sequence of testing was chosen to determine how muscle performance and muscle soreness changed over time as a result of the exercise session, and whether NSAID use impacted the tests.

What they found

When all the tests were run and all the analysis was performed, the results were pretty clear (see figure 1). Unsurprisingly, muscles soreness in the muscles of the legs was elevated following the plyometric session. However, there were no differences between the groups (ibuprofen, flurbiprofen, celecoxib, and placebo) in terms of the degree of muscle soreness. Interestingly, while vertical jump measurements were depressed four hours following the plyometric session, it was actually higher than baseline 24-hours later. Again, there were no differences in between treatment groups. One potential criticism of the study could be that the plyometric session wasn’t difficult enough. However, it was in line with other protocols designed to create muscle damage.

Figure 1: DOMS scores and NSAID/placebo use

Related Files

In terms of muscle strength measurements, there was once again no difference between the treatment groups when measured 24 hours after the exercise session. There was a slight benefit for celecoxib as compared to placebo at four hours post exercise. However, there was no benefit for celecoxib as compared to the other NSAIDS at four hours. Overall, these results indicate that there is little to no benefit for the use of NSAIDS following a challenging exercise session!

Practical applications

The results of this study raise questions as to the value of using NSAIDS in relation to the management of losses of performance following intense exercise. This is particularly true when considering the evidence that NSAID use may compromise long-term training adaptation as well. If you’re going to use NSAIDS, it may make sense to restrict their use to those occasions where you believe they are absolutely necessary. If you are a long-term user, it’s well worth considering whether continued use is justified, particularly in light of this research and given that the long-term side effects are very real.

Celecoxib (brand name Celebrex) may improve performance decrements. However, Celebrex is a prescription NSAID, likely making availability an issue. Beyond issues of availability, it is probably not the best idea to routinely take prescription grade painkillers in the hope for modest improvements in muscle recovery following intense training. Even then, improvements were not seen in movement performance as demonstrated by the vertical jump - only in isolated muscle testing.

These drugs should be used cautiously as they have potential negative consequences, and may not work as well as is often believed, or at all. If you feel the need to take NSAIDs to manage training-related soreness, you are almost certainly better off looking at the structure of the training program to ensure that the balance of loading/intensity and training frequency is appropriate. Not only may NSAID use be compromising your long-term training adaptations, it may not be helping to solve the soreness problem in the first place!

References

1. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep 11, 43–50 (2023). doi.org/10.1007/s40141-023-00381-y

2. J Sci Med Sport. 2024 May;27(5):287-292. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2024.02.002. Epub 2024 Feb 13

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.