Ultrarunners: are you prepared for the big one?

You need to know what you are letting yourself in for when you sign up for an ultra run or stage race. The allure of the Marathon des Sables, the Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc or a more local 100-miler may seem like a bucket-list challenge waiting to be ticked off. But if you want to make sure it doesn’t tick you off, you need to prepare specifically, logically and systematically. You also need to know what’s likely to affect you and what’s not. In this article, John Shepherd takes a look at some of the science underpinning successful ultra-running, and also seeks advice from accomplished ultrarunners.

Who are ultrarunners?

Researchers identified that the typical ultrarunner is aged between 30 and 54 and maleInt J Sports Physiol Perform. 2012 Dec;7(4):310-2. Somewhat logically, ultrarunners have completed more marathons than marathon runners. However, recreational marathon runners tend to have faster marathon PBs than ultrarunners. So it could be that ultrarunners adapt to running at slower paces or are potentially slower in the first place. Successful ultrarunners are likely to have around seven and a half years of specific ultramarathon experience. Not surprisingly, the researchers found that ultrarunners complete more running kilometres in training than marathoners, but do so more slowly (we will discuss mileage in greater depth in this article’s case studies and also next month’s issue). Table 1 provides some more data comparing ultra and marathon runner, where we specifically address the question of how much mileage is enough?TABLE 1 COMPARISON OF ANTHROPOMETRY AND TRAINING BETWEEN 24 HOUR ULTRAMARATHONERS AND MARATHONERS

| Ultramarathoners | Marathoners | Significant difference? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.0 | 42.8 | Yes |

| Body mass (kg) No | 72.8 | 73.9 | No |

| Body height (m) | 1.77 | 1.78 | No |

| Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) | 23.0 | 23.4 | No |

| Circumference of upper arm (cm) | 28.4 | 29.2 | Yes |

| Circumference of thigh (cm) | 53.3 | 54.9 | Yes, very |

| Percent body fat (%) | 16.0 | 16.2 | No |

| Skeletal muscle mass (kg) | 37.0 | 38.1 | No |

| Years as runner | 13.5 | 10.5 | Yes |

| Weekly running hours | 9.1 | 4.8 | Yes, very |

| Weekly running distance (km) | 86.5 | 44.7 | Yes, very |

| Average speed in running training (kmh) | 10.2 | 11.0 | Yes, very |

When comparing recreational athletes, the ultramarathoners tended to be older, run more hours and miles but at a slower speed, and be more experienced. However, apart from arm and leg circumference being less, in all other respects, they were anthropometrically similar to 26.2-mile marathon runners.

Injury risk, health and experience

You might think that ultrarunners would suffer from more injuries than marathon runners. However, the research that exists indicates otherwise. And contrary to what many also think, ultrarunners don’t end up taking more days off work as a result of their exploits! Researchers looked at the health of 1,212 active ultrarunnersPLoS One. 2014 Jan 8;9(1):e83867. The team looked at the prevalence of chronic diseases, health-care use, and risk factors for exercise-related injuries among the runners. From a health perspective, the most common chronic medical conditions were allergies/hay fever (25.1%) and exercise-induced asthma (13.0%). But there was a low prevalence of serious medical issues such as cancers (4.5%), coronary artery disease (0.7%), seizure disorders (0.7%) and diabetes (0.7%).In terms of exercise-induced injuries most (64.6%) suffered from one that resulted in lost training days (typically around 4 days). Knees were the most reported injury, while the incidence of stress fractures was 5.5% and most involving the foot (44.5%). Significantly, there was a higher prevalence of stress fracture among women (see box on females and the athlete triad later).

Interestingly it was also discovered that the ultrarunners who had the most injuries were younger and less experienced than those without injury. So, experience seems to matter as an indicator of successful ultra event preparation. Gaining valuable insights into what your body can and cannot handle training-wise is crucial, and as indicated from the research, may take time (see the case studies for some very real practical application of experience).

Acute kidney injury

An issue that ultramarathoners may face as a result of prolonged effort coupled with dehydration is acute kidney injury (AKI), which involves a loss of kidney function – see figure 1. There are three stages to this condition, which occurs largely as a result of decreased kidney blood flow. Researchers looked at the incidence of AKI in 26 runners participating in a 100km ultramarathon in Taipei, TaiwanPLoS One. 2015 Jul 15;10(7):e0133146. It was discovered that 84.6% (22 runners) developed symptoms of AKI. Most exhibited those of stage 1 and none stage 3 symptoms (stage 3 being the most severe).Dehydration, improper fluid balance and urinary tract difficulties are the key factors that influence the risk of developing of AKI in ultramarathoners. Further research has identified similar outcomes, but the good news is that most reports a return to near normal kidney function between stages and after completion of the ultra eventRes Sports Med. 2014;22(2):185-92 Clin J Sport Med. 2016 Sep;26(5):417-22. It seems then that for the majority of ultrarunners, AKI is something that may well be experienced in an ultra event, but which shouldn’t have long-term consequences for the majority of runners. Remaining hydrated and taking on board sufficient amounts of electrolytes will do much to offset AKI (more later).

FIGURE 1: ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY

Cramping

Ensuring optimum sodium and fluid replenishment is crucial for ultra and stage races. However, it may not sufficient in itself to prevent cramping. Researchers have discovered that runners with a prior history of cramping and muscle damage were more prone to suffering from these conditions compared to runners who did not have this specific history - regardless of impaired sodium and fluid balanceSports Med Open. 2015;1(1):24. Epub 2015 May 21.The research was conducted on runners in a 161km ultra and involved pre and postrace blood tests and a post-race survey. It was noted that those who suffered from cramping had higher levels of creatine kinase in their blood concentrations. Creatine kinase is an indicator of AKI, so although you may be optimally or near optimally hydrated and have taken on board sufficient electrolytes, it appears there’s still the potential to suffer from cramping if you are so predisposed. (Ed: for more information on cramping and a new nutritional approach to help prevent it, see Sports Performance Bulletin issue 356)

Hydration

Hydration in ultra and stage races is a subject in its own right and beyond the scope of this article. However, it’s advisable to try to work out how much fluid your body will lose and (where practical given the specific ultra/stage race you are preparing for) how to implement a hydration strategy that reflects this. You can do this quite simply by weighing yourself before a run and then afterwards. The loss of body mass will approximate your fluid losses. However, to obtain meaningful results, you should try to train in similar conditions to the ones you will confront in your event.Training in a heat chamber may afford you with an opportunity to be more specific. If you are a ‘cramper’, you may also be able to monitor roughly when cramping occurs and try to take preventative measures. Hydration needs to be a constant process when competing in ultras and stage races – starting before, continuing throughout and after each stage and upon race completion where appropriate.

One team of researchers offers some succinct advice for those considering hotweather ultramarathons. Their research involved 381 starters in a 161k ultramarathonRes Sports Med. 2014;22(3):213-25. They concluded that ‘a weight loss greater than 2% does not necessarily have adverse consequences on performance’, and that ‘the use of sodium supplements or drinking beyond thirst is not required to maintain hydration during ultra-endurance events with high thermal stress’.

It should be pointed out however that another study found that successful finishers in a similar ultra-event exhibited a greater rate of fluid consumption and more closely met their calorific (energy replacement needs) in contrast to non-finishersJ Am Coll Nutr. 2002 Dec;21(6):553-9. Electrolyte consumption was broadly similar.

One aspect of hydration that also needs to be considered in the light of knowing how much to drink and what you can “get away with” is over drinking (a condition where too much fluid consumption dilutes the percentage of electrolytes in the body and the amount of water in the body increases). This condition can impair performance and is known as hyponatremia. A survey of 76 runners in a 225k semi-sufficient stage race discovered that 42% showed some signs of hyponatremia Nutr J. 2013 Jan 15;12:13.. As well as attempting to work out individual hydration needs and attempting to not over drink, it’s also important to practise drinking literally on the run, as this is not as easy as it may sound. Also, particularly in stage races the desire to drink more water can decline as it becomes a “chore”. But it is a necessity. Flavouring your drinks with a carb-based solution may assist, but note that concentrations above 3% can be counterproductive.

The topographical ups & downs

Many ultras include climbing, as of course does the sport of Skyrunning. Skyrunning involves mountain running up to or exceeding 2,000m, where the incline exceeds 30% and the climbing difficulty does not exceed 11% grade). Negotiating steep terrain confidentially and as economically as possible is therefore crucial.Much research exists as to how the body adapts to these ups and downs. Researchers looked at the effects that the Tor des Géants (one of the world’s toughest mountain ultras – see figure 2) had on the performance of runners over varied terrain (level and uphill)Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014 May;114(5):929-39. The runners were tested before and after the Tor des Géants and it was discovered that they adapted their uphill gait by increasing contact time during each footfall, and a decrease in leg swing going into the next stride. These are not that surprising outcomes given the need to conserve energy in such events. Highly relevant was the fact that the runners’ energy cost for running uphill decreased by 13.8% by the end of the event.

Similar results were found after the ‘Extreme Mountain Ultra Marathon (MUM)’ - i.e. that the energy cost of uphill locomotion (walking and running at different speeds) decreased over timeFront Physiol. 2016 Nov 8;7:530. eCollection 2016. The obvious message here then is to prepare topographically as specifically as you can for the ultra that you will be facing. If you’re training for an extremely hilly ultra, you need to be training on extremely hilly terrain.

One of the world’s best endurance athlete Kilian Jornet does just this. A cursory look at his training will identify that he often only completes less than 50 miles a week. However, Jornet has won virtually every mountain running event and ultra there is worth winning: the UTMB four times, the Hard Rock 100 two times, and he’s also run up and down Everest twice in a week! What enables Jornet to do this (apart from his superb genetics) is the emphasis in training on gaining altitude. Jornet’s typical weekly ascent is 29,000 metres (95,700ft). He trains specifically to master the typical conditions he faces when he competes or challenges himself, and as much as possible, so should you.

Figure 2: Altitude profile of Tor des Géants

Can’t stand the heat?

Heat also needs its own specific preparation. Heat is an obvious potential issue in races such as the Marathon des Sable (across the Sahara desert). Ultrarunner and Team GB trail team representative Damian Hall (see case study) competed in a 230km multi-stage race in Costa Rico in high humidity (80-90%) and heat (high 30s C). Damian carried out some very specific preparation in order to better acclimatise himself to the conditions at home in Bath, England.Specific heat acclimatisation training enables your body to create more blood plasma (fluid), which will provide more fluid to aid sweating, which will in turn aid your cooling. It also helps stave off dehydration. One of the things that Hall did involved running in extra layers of clothing. This obviously generates greater heat and starts to change the way the body sweats and regulates.

As he explained: “It was fun for about ten minutes. Then I got all hot and bothered and slow. But after a week or so, I was finding running in my self-generated heat chamber easier, and after a couple of weeks it felt normal.” Hall then built on this for his preparations for the Costa Rico Costal Challenge by doing some sessions in a specific heat chamber. Although he only had time for a few sessions he felt that each was a little easier than the one before. The first had been at a temperature of about 25C with humidity set at 80 percent. Did his preparations work? Hall thinks so as he finished fifth in the race.

Hall’s personal acclimatisation programme may appear relatively short at least in terms of the heat chamber sessions – he actually only had three. However, there’s good science to back up his experiences – ie that not many sessions may actually be required to develop an adaptive response. Indeed, researchers have reported that: “Preventing exertional heat illness and optimising performance in ultra-endurance runners can occur with exposure to at least two hours of exercise-related heat stress on at least two occasions in the days leading up to multi-stage ultramarathon competition in the heatEur J Sport Sci. 2014;14 Suppl 1:S131-41.”

“Hopefully this article has given you some key pointers for those thinking of an ultra event. See below where you can read more about Damian Hall’s approach, for a bit more insight!”

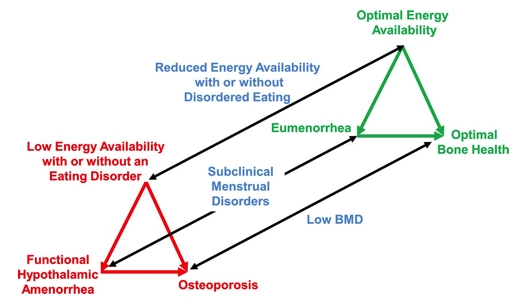

FEMALE ULTRARUNNERS AND INJURY

Stress fractures can be a common injury concern for ultrarunners particularly females. In relation to this, it seems that female ultramarathon runners may also be at risk from the female athlete triad (see figure 3) and that they may need to be better informed about how to avoid this and adjust their training and nutrition accordinglySports Med Open. 2015;1(1):29. Three-hundred-and-six female entrants in South Africa’s Comrades Marathon took part in a survey to test their awareness of the female athlete triad. When questioned 92% had not heard of it and only three were able to name the three components – amenorrhoea (cessation of periods), disordered eating and loss of bone mineral density. In fact the researchers discovered that 44.1% of the survey’s participants were at risk of the female athlete triad and that a third demonstrated disordered eating patterns.It was also noted that postmenopausal women were specifically at risk of loss of bone density if they didn’t adequately eat to fuel their training. This is particularly relevant given that many ultrarunners are master athletes, and therefore more prone to potential bone loss. The obvious take-home message if you are a female ultrarunner – be aware of the female athlete triad and eat and train accordingly.

Figure 3: The ‘female triad’ spectrum

CASE STUDY: Damien Hall

Damian Hall, although an outdoor and fitness journalist by profession, has almost become an elite ultrarunner partly because of his assignments and associated accumulated knowledge. Hall has represented GB at the IAU Trail World Championships, and recently finished 12th (first Brit) at the 105-mile UTMB (the world’s biggest trail race) and 17th in the prestigious 2017 Ultra-Trail World Tour. In the UK he gained podium places at the Spine Race, Dragon’s Back Race and the UK Ultra Trail Championships, and set a fastest known time for our longest National Trail, the 630mile South West Coast Path (10 days, 15 hours and 18 minutes).

Damien completes anywhere from 50 to 100 miles per week. But his miles aren’t all equal. The races he likes best are mountainous, so he trains on gradient. UTMB for example has 32,000ft of ascent (more than Mt Everest), so in the build-up to that he tried to accumulate around 20,000ft of vertical gain a week. This wasn’t always easy in the Cotswolds near Bath, so he headed to the Brecon Beacons as often as possible, a three-hour round trip. Damien also does regular strength sessions and practises power hiking, without and without a weight vest.

In addition, Damien performs foam rolling and a dynamic stretch routine every day. He also aims to have fortnightly massages with his physio. He drinks alcohol very rarely, eats plenty of fruit and vegetables and tries to get eight hours’ sleep per night. As Damien puts it “Running’s made me pretty boring. But it’s all worth it!”

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.