You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Golf: the gentle game that can lead to pain

Although golf is regarded by many as a ‘gentle’ sport, the risk of lower back pain is surprisingly high. Why is this the case and how can athletes who enjoy playing a bit of golf ensure they remain injury free, or recover rapidly should injury occur?

The sport of golf originated in 15th-century Scotland, but has evolved into a globally popular activity, with an estimated 55 to 80 million golf enthusiasts participating regularly in more than 130 countries (indeed, you may be one yourself!). The slower, more leisurely nature of the game makes it popular with older adults who may be unwilling or unable to take up a more punishing sport, but it is also popular among some athletes looking to enjoy outdoors leisure time pursuing an activity that is not so demanding that it detracts from performance in their main sport. Regardless, the amount of physical activity required to play golf is still sufficient to provide significant health benefits.

Injury surprise

Although its less demanding nature makes it seem otherwise, the risk of injury from playing golf is significant and larger than many people imagine. While a properly executed golf swing may not appear particularly stressful, a number of biomechanical studies have demonstrated that many joints and limbs are actually moving at high velocity and through extreme ranges of motion (ROM, making them vulnerable to injury)(1-3). To make matters worse, the successful execution of the golf swing requires a high degree of coordination, requiring many hours of practice during which these powerful movements are repeated hundreds of times. Add the fact that faulty swing mechanics are more likely to lead to an injury, and that the golfers with poor swing actions are the most likely to be practicing, and you have a sure fire recipe for injury!

Prevalence of injury

Putting aside the risks of being struck by a golf club, ball, a golf cart or even lightening(!), injuries related to golf practice are most likely to afflict the trunk and upper body. Studies show that hand/wrist injuries and elbow injuries are quite common, affecting around 13-20% and 25-30% of amateur golfers respectively. Shoulder injuries are also quite common, affecting around 8-18% of amateur golfers. The corresponding figures for professional golfers tend to be significantly lower however – most likely because of better technique(4-7).

The incidence of low back pain (LBP) among golfers of all abilities by contrast is a rather more common, and is known to affect amateurs and professionals alike, regardless of skill levels(8). Epidemiological studies have shown that low back conditions account for approximately 25% of all golf injuries(9,10) although incidence rates as high as 54% have been reported(11). Worryingly, many who play golf may not be aware of the risks; in a study that surveyed 196 golfers who had just taken up the sport, 25% suffered back pain during the one-year study period, yet the vast majority of these participants were unaware that playing golf was linked to their LBP(12). The authors concluded that their golf activity likely aggravated pre-existing back pain due to the forceful nature of the movements associated with playing and practicing.

The demands of the swing

To understand how something as apparently benign as golf can lead to a high incidence of lower back pain, it helps to appreciate the biomechanics of the swing (see figure 1). The golf swing involves a slow deliberate rotation of the trunk away from the target (the backswing) followed by a powerful rotation of the trunk towards the target on the downswing. Although there are other spinal motions present during the swing movement, the axial twisting forces are especially noteworthy because this type of twisting has been identified as a significant risk factor for low back injury disorders in occupational settings(13).

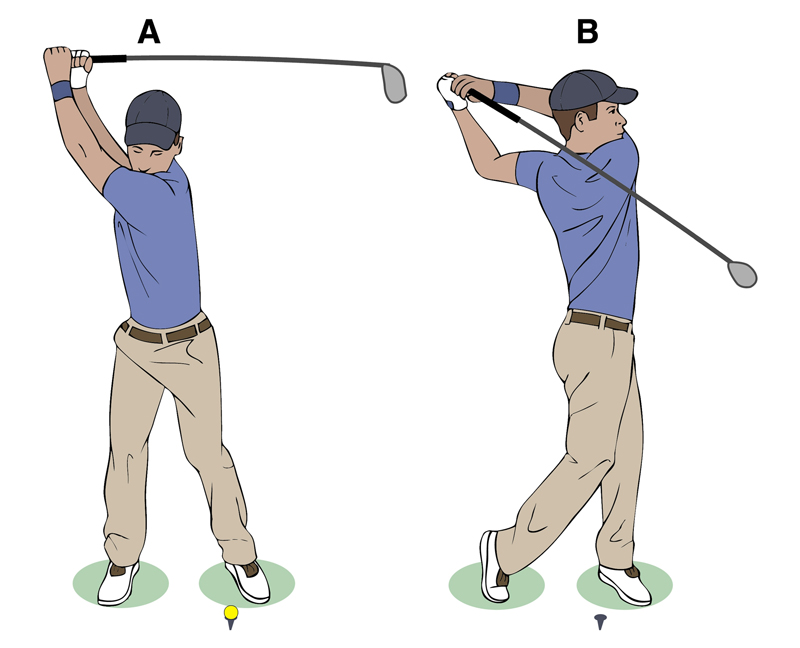

Figure 1: the golf swing (right-handed golfer)

Studies investigating the axial forces at play during the swing motion have come up with some startling findings. One of the first studies looked at forces on the lower back during a full golf swing while using a five iron – specifically the compressive, shear, lateral-bending and rotational loads on the L3/4 segment of the lumbar spine(14). Kinetic and muscle activity data was collected from four amateur and four pro golfers. Shear loads were high in both groups but were higher in the amateurs, averaging 596 Newtons of force vs. 329 Newtons in the pros. Compressive loading on the other hand was higher in the pros, averaging nearly 7,600 Newtons vs. 6,100 Newtons in the amateurs.

To put these compressive loads in perspective, consider that the swing of a pro golfer generates compressive forces around eight times his/her bodyweight and that of an amateur around six times bodyweight. Now consider that spinal compression forces in a runner are around three times body weight, and you can begin to appreciate the problem. It is also worth noting that cadaver studies have shown disc prolapse typically occurs with compressive loads of around 5,500 Newtons, which explains why the swing motion can increase the risk of an acute low back injury(15).

Despite the risk of acute low back injury as a result of the swing, many golf players report a gradual and insidious onset of LBP rather than in a single event. Insidious LBP is thought to occur as a result of cumulative loading as a result of the combination of large magnitude spinal forces combined with a high frequency of swing repetitions. Studies show that elite golfers who consistently suffer LBP during golfing activities tend to have a higher frequency of swing repetitions (ie spend more time playing and practicing) than symptom-free golfers(16). Cumulative loading also likely explains why elite players identify overuse rather than a traumatic event as the cause of their LBP(17).

Asymmetry and LBP

As we can see in figure 1, a relatively slow backswing followed by a powerful downswing and follow-through produces an asymmetrical trunk rotational velocity, leading to differences in spinal loading patterns between the lead and trail sides of the lumbar spine. Indeed, studies show that LBP predominantly occurs on the trail side – ie the right side of a right-handed golfer and radiological investigations of elite players have demonstrated a significantly higher rate of arthritic change on the trail side of the vertebra of the spine than age-matched control subjects(11).

Other researchers have also noted that both left axial rotation velocity and right side-bending angles on the downswing reached peak values almost simultaneously and just after ball impact, coinciding with the point at which the majority of players in their study report experiencing LBP(18). In plain English, a large amount of side bend angle combined with trunk rotation through the impact phase damages the lumbar spine by creating excessive intervertebral lateral shear (where the one vertebra move sideways relative to its neighbour). This shearing motion is potentially harmful since it is resisted primarily by disc strength rather than bone strength, thereby resulting in injury and pain, particularly on the trail side.

One way to reduce lateral shear is to decrease right-side bending (in a right-handed golfer). Studies show that players with LBP tend to address the ball with more spinal flexion - ie they slouch more and use more side-bend during the swing than healthy golfers(19). The good news for golfers is that decreasing the amount of right side-bend on the downswing may be as simple as using better posture when setting up over the ball. It’s also important to note that the use of shorter clubs encourages right-side bending and that longer clubs may help in this respect.

The ‘X’ factor

In an effort to hit the ball harder and further, many golfers develop a pronounced backswing, which in theory at least allows more time for maximal force to be generated before ball contact. More backswing generates higher axial loading in the spine. This is especially the case during the initial stage of the downswing when the pelvis starts rotating towards the target a fraction before the shoulder. The idea is to generate the maximum ‘X’ factor stretch. A skilled player can increase this ‘X’ factor stretch by as much as 19% during the initial phase of the downswing.

The problem of course is that this additional stretch presents even higher loadings to the spine. An over-rotation (sometimes referred to as ‘supra-maximal twisting’) of the trunk while performing the golf swing increases the risk of spinal irritation and subsequent LBP. Moreover, many golfers are unable to replicate this degree of rotational stretch in the clinic when asked to do so from a neutral posture at a moderate speed. This has led some researchers to question whether the X-factor loading can be reduced.

One study found that reducing the relative amount of spinal rotation or torsion by increasing the range of hip turn during the backswing could help in cases of golfing-related LBP(20). In another study, researchers questioned whether an extreme backswing was even necessary(21). The researchers investigated the effects of using a shortened backswing on ball-contact accuracy and club-head speed. The results showed that restricting the backswing by almost 20% (thereby reducing spinal loading) had no negative effect on overall swing performance.

Together, these and other results have led some researchers to suggest that golfers with LBP adopt a more ‘classic’ golf swing – as used in an earlier era of the game. The classic swing incorporates a reduced X factor, which decreases the torque and subsequent stress on the lumbar spine. This is achieved by allowing the lead heel (ie left heel in a right-handed golfer) to lift during the backswing to allow the pelvis (and not just the shoulders) to turn away from the target.

Getting to the core of it

Given the role of trunk musculature in generating the swing movement (both downswing and backswing), it’s unsurprising that researchers have investigated whether core muscle function (or dysfunction) is implicated in golf-related LBP. Some studies do indeed suggest that golfers with LBP appear to activate their trunk muscles differently to symptom-free golfers, and it’s possible that over time, these differences contribute to reduced trunk muscle strength and endurance.

For example, one study found that the onset times of major bursts of activity from some of the abdominal muscles were delayed in the golfers suffering LBP(22). In particular, the lead external oblique (left in right-handed golfers) was activated significantly later during the backswing in the golfers with LBP when compared to asymptomatic controls. Another study looked at EMG (muscle electrical activity) in the abdominal and trunk muscles of golfers with and without LBP, and found that highly skilled players tended to demonstrate reduced erector spinae activity at the top of the backswing and at ball impact(23).

A small number of studies have compared trunk muscle endurance in golfers with and without LBP. For example one study investigated the total time golfers with and without LBP could maintain an isometric transverse abdominis contraction and found that healthy golfers were able to maintain the static contraction for significantly longer than the golfers with LBP(24). This is relevant because transverse abdominis is known to be very important for protecting the lumbar spine by tensioning the connective tissue around it(25).

Another study found that static trunk extensor (eg erector spinae) holding times for golfers with LBP was significantly lower than values reported from healthy subjects(26), and an Australian study on trainee golf professionals found that golfers with a trail side (ie right side for a right-handed golfer) deficit of 12.5 seconds on the static side-bridge endurance test reported more frequent episodes of moderate to severe LBP(27). Further evidence indicates that elite golfers tend to have greater axial rotation strength in the direction they normally swing a golf club (ie to the left for a right-handed player) and that this asymmetry or imbalance is likely to be more pronounced in golfers with LBP(28). Together, these findings suggest that all golfers, but especially those prone to LBP should perform some regular core stabilization training exercise (see box 1).

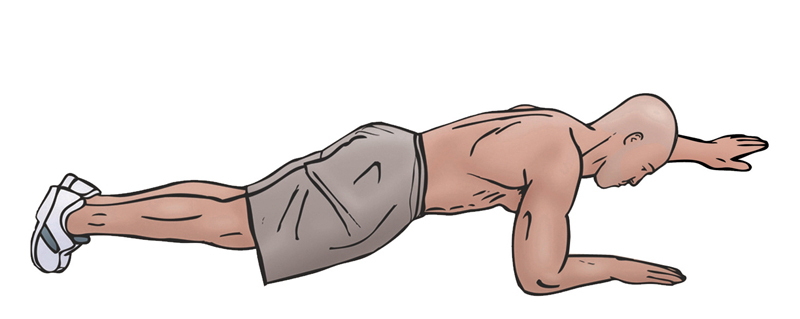

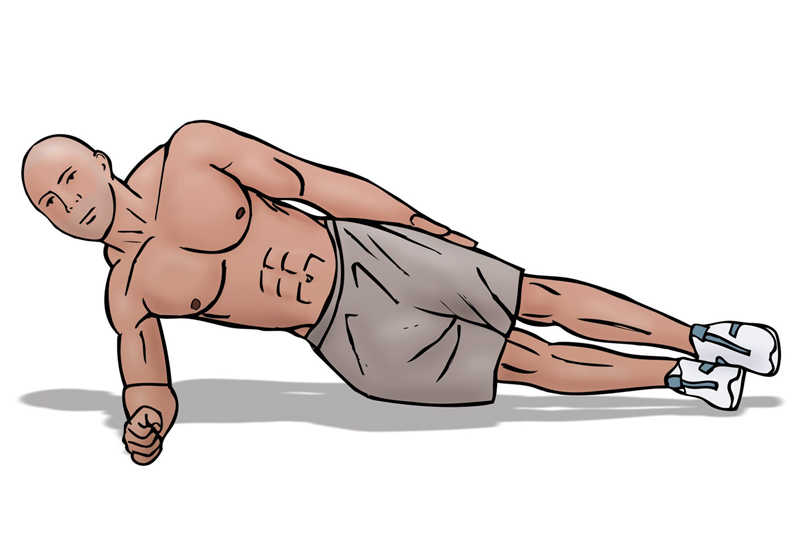

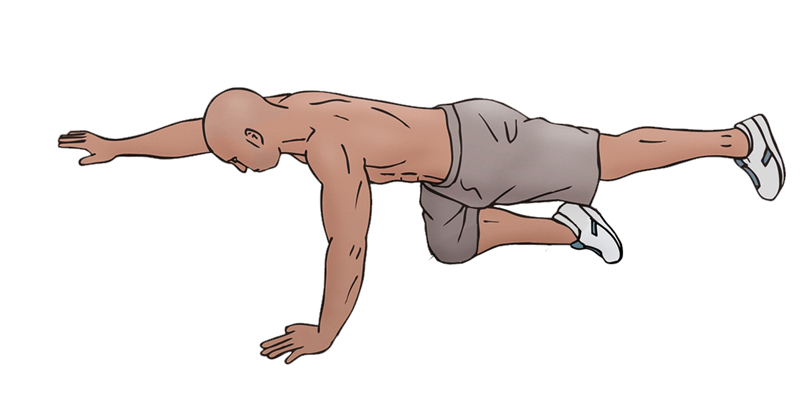

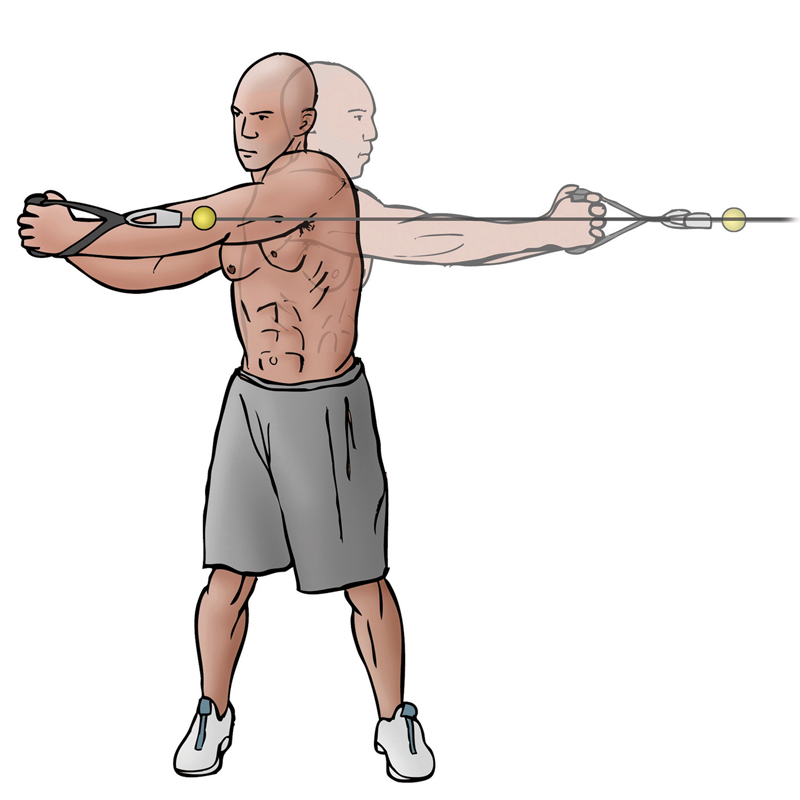

Box 1: Core stabilisation training suggestions for golfers

Exercises that improve transverse abdominis and multifidus strength and endurance are especially recommended. Of particular importance is ensuring any side-to-side asymmetry is minimized – something that should be emphasized at all times.

Practical implications for athletes who play golf

If you’re an athlete who likes to indulge in a bit of golf – or indeed, if golf is your main sport - the key take home message is that because of the movement patterns and loadings involved, golf carries more injury risk than is generally realized, especially to the lower back. If you play golf and suffer back pain therefore, it’s more than likely that the regular practice of your sport will be a major contributing factor. To avoid this situation occurring – or even better, to prevent it – you will likely need to modify your training and playing habits, with a special emphasis on trunk strengthening using core training exercises. Below are some key recommendations on golf practice that can speed recovery and reduce the risk of re-injury:

· Adopt a common sense approach to play/practice volume; while playing and practicing will improve your performance, you need to be aware of the spinal stresses that golf practice produces and find a balance between participation volume and recovery from LBP.

· Address asymmetries in trunk musculature/strength between the lead and trail sides produced by high-volume, repetitive practice of golf swings. This means performing bilateral strengthening exercises and taking both left and right-handed practice swings.

· Improve your trunk rotation flexibility, which helps control the relative over-rotation of the spine during the golf backswing. Make sure you lift your lead heel at the completion of the backswing, which allows more pelvic rotation, in turn reducing spinal torsion.

· Improve the strength and endurance of your spinal stability muscles using a variety of core exercises.

· Work on improving your hip rotation and range of movement, especially on the lead side. During the swing, the body pivots onto the lead side; a reduction in the amount of hip rotation on the lead side can cause increased movement and force to be transmitted to the lumbar spine resulting in LBP.

· Always perform a thorough warm up prior to playing/practicing and rather than carrying your golf clubs on your shoulder, use a push cart, which is vastly preferable.

· Last but not least, one of the best things you can do is seek professional assistance from a properly qualified golf coach to assess swing mechanics and determine if there is a need to decrease the amount of spinal side bend on the downswing and through impact. Improving posture over the ball is an example of the way this can be achieved.

References

1. J Appl Biomech. 2002;18:366–73

2. Sports Med.2005;35(5):429–49

3. J Appl Biomech. 2011;27(3):242–51

4. Am J Sp Med. 2003;31:438–443

5. Phys Sports Med. 1990;18:122–26

6. Br J Sports Med. 1992;26:63–5

7. Phys Sports Med. 1982;10:64–70

8. Clin Sports Med.1996;15(1):1–7

9. Br J Sports Med. 1992;26(1):63–5

10. McNicholas MJ, Neilsen A, Knill-Jones RP. Golf injuries in Scotland. Human Kinetics; 1999

11. Low back injury in elite and professional golfers: an epidemiologic and radiographic study. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1999

12 Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(5):659–64

13. Ergonomics. 1995;38(2):377–410

14. Biomechanical analysis of the golfer’s back. Cochran AJ editor. London: E and FN SPON; 1990

15. Mechanics of the intervertebral disc. Ghosh P editor. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 1988

16. J Sports Sci. 2002;20(8):599–605

17. Phys Sportsmed. 1982;10:64–70

18. Morgan D, Sugaya H, Banks S. A new twist on golf kinematics and low back injuries. South Carolina: Clemson University; 1997

19. J Sports Sci. 2002;20(8):599–605

20. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(10):1667–73

21. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24(9):569–75

22. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(10):1647–54

23. J Sci Med Sport. 2008;11(2):174–81

24. J Man Manip Ther . 2000;8:162–74

25. Phys Ther. 1997;77(2):132–42

26. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(16):E361–6

27. Phys Ther Sport . 2005;6:122–30

28. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2006;1(2):80–9

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.