You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Injury rehab: talking at cross purposes!

SPB explains the ‘cross-education’ effect in injury rehabilitation, and looks at new research highlighting how athletes can use it to their advantage

For the dedicated athlete, nothing is worse than injury. There’s not only the physical pain to contend with, there’s also the disruption to activities of daily life, and the inability to do what you love to do. In addition, you know that every day without consistent training results in a loss of sporting fitness. It’s an all-around nightmare for someone that loves to train and compete!

Overcoming injury

Once injury strikes, the thought process needs to shift from ‘how can I continue to improve?’ to ‘how can I get back to full health as quickly as possible?’. The initial response is often geared towards recovery strategies such as icing, heating, or manual therapies designed to increase recovery of the damaged tissue. This is certainly a wise decision, especially when it appears to be a short-term problem. However, when an injury is likely going to require an extended recovery period, a more thorough approach is necessary.

One strategy that is often overlooked is continuing to actively train while injured. Many athletes hesitate to do so because they don’t want to create an imbalance between the injured and the uninjured limbs. As we’re going to see, this is a potentially costly mistake. This is because there’s a phenomenon known as cross-education effect, where training one limb results in significant improvements in strength in the non-trained limb. More interestingly, this effect seems to be stronger when performed with eccentric training rather than concentric training.

Cross education for injury rehab

Cross-education has largely been thought to be a phenomenon of the nervous system. It was believed that better coordination of the trained limb transferred over to the untrained limb. While it’s likely this effect contributes a significant portion of the benefits, it appears that there may be structural benefits as well. In several studies involving immobilized limbs (due to injury), training the non-immobilized resulted in reduced loss of muscle mass in the immobilize limb, indicating that any cross over effects may go beyond just adaptations in the nervous system. That’s good news for the injured athlete who wants to limit losses in muscle mass.

Beyond potential losses in structure and function, part of the problem with injury is that the injured limb also loses its ability to withstand the rigors of exercise. Following inactivity or a lack of training stimulus, muscle tends to experience much more damage following exercise than usual. This makes it more difficult to mount a training comeback, as well as increasing the risk of injury. As with cross-education, eccentric training is most effective at preventing this loss of function.

In short, injury or immobilization is a significant threat to the structure and function of muscle. It appears that training the non-immobilized limb may confer significant structural and functional benefits to the immobilized limb, in spite of complete inactivity of that immobilized limb. To what degree are these benefits experienced? That’s the question examined by the research study we’re going to look at in this article.

The study

In this research, a group of Taiwanese researchers took 36 sedentary men and separated them into 3 groups(1). For all three groups, the subjects’ non-dominant arms were immobilized for 3 weeks. Those are some pretty committed subjects! Over the course of the next three weeks the following protocol was followed:

- One group performed eccentric only strength training with their dominant arm.

- One group performed concentric only strength training with their dominant arm.

- One group performed no training at al (control group).

The training consisted of five sets of 6 x dumbbell curls, performed with either eccentric or concentric only contractions.

To test the impact of the different interventions, the researchers measured muscle strength, muscle activity, and muscle size before and after the 3-week period. The subjects also performed 30 eccentric contractions of the immobilized arm after the three weeks. Each day for the 5 days following this test, muscle strength, muscle soreness, range of motion, and creatine kinase (an indicator of muscle damage) were measured to assess how well the two training interventions protected against the damaging effects of exercise.

What they found

The results were stunning. Unsurprisingly, measures of muscle strength and muscle size were significantly decreased in the immobilized arm of the control group. In terms of muscle strength, these strength losses in the immobilized arm were almost completely eliminated with the concentric training group. Even more shocking was that the immobilized arm actually gained strength in the eccentric group (see figure 1)! It terms of muscle size, the concentric group still exhibited muscle loss, although much less than the control group. The eccentric group experienced no muscle loss in spite of literally performing zero movement for three weeks!!

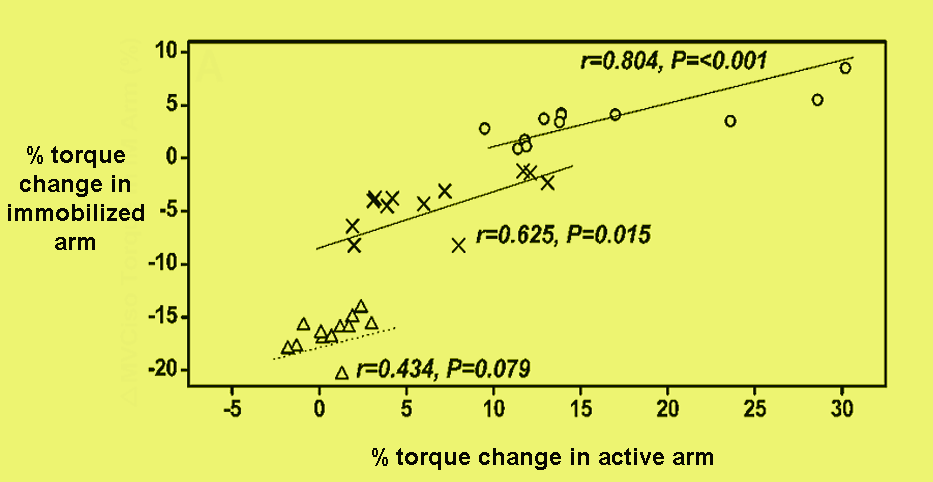

Figure 1: Strength changes in eccentric/concentric training and control conditions

Circles = eccentric training group; crosses = concentric training group; triangles = control group (no training). The control group lost 15-20% maximum force production in the immobilized arm. The concentric group gained up to 10% maximum force in the trained arm and lost only 5-10% in the immobilized arm. The eccentric group gained 10-30% maximum force in the trained arm and actually gained around 5% in the immobilized arm!

When it came to the protective effects against muscle damage, eccentric training was significantly more effective than concentric training and the control group in all measures. The concentric training program was also significantly more effective than the control group in all measures. This means that even though no exercise was performed with the immobilized arm, it was protected against the damaging effects of exercise by training the non-immobilized arm either eccentrically or concentrically. Pretty amazing!

Practical implications for athletes

When injury strikes, it appears that training the non-immobilized limb has a major impact on the structure and function of the immobilized limb. It reduces losses in strength, it reduces losses in size, and it reduces losses in the ability to prevent muscle damage following intense exercises. These are all benefits that are of tremendous value to athletes of all types. Importantly, these effects appear to be magnified by eccentric training compared to eccentric training. In times where one limb is out of action, it looks like there’s a lot that can be done to reduce the negative impact of such a situation!

For athletes who get injured, a setback is inevitable. However, effective strategies exist to minimize how large that set back is going to be. By training the uninjured limb, it’s very likely that you will be able to reduce the impact of a lack of training on the uninjured limb. Pretty cool! Even better, it doesn’t take a lot of time or effort. All it takes is a commitment to continuing to train, and potentially some creativity as to how you can maintain this training effect if one limb is out of action.

Related Files

Caveats

There are some caveats that should be considered. It’s important to note that this study was just performed on the arms. However, while it can’t be definitively concluded that similar effects would be found in the legs, there’s no reason to expect that wouldn’t be the case. Secondly, these subjects were untrained, which means two things. First, they were unaccustomed to the training which likely resulted in a more robust training response due to the novelty of the intervention. Secondly, because they weren’t training, they didn’t have any training-induced adaptations to lose, likely limiting how much of a loss of function they experienced. That being said, it’s likely that the effect would still be present in a trained athlete, although the magnitude of the effect would likely be less.

Despite these potential limitations, when you’re injured, any way to minimize the loss of training adaptations is well worth the effort. And even if the results aren’t as significant as those in this study, if you’re injured, you’ll have time to do something, so you might as well do what you can! Just as importantly, continuing to feel like you’re doing something to help your situation will do wonders psychologically, both during the injury period and when ramping back up to speed. For all these reasons, any progress that can be maintained is a worthy time investment.

When it comes to the strength, it appears that eccentric training is particularly effective relative to concentric training. When possible, emphasize eccentric training. However, concentric only was still effective at mitigating losses of function and structure, just not as effective as eccentric only training. If for some reason eccentric training is not an option, it’s still valuable to perform some sort of training, even if it’s concentric only training. Training the uninjured limb in some manner will likely help you retain more of your function.

Another key takeaway is that it doesn’t take much training to make an impact. Over a 3-week period, the subjects only performed six sessions. Each session only consisted of 5 sets of 6 repetitions. This is an incredibly small time commitment considering the potential benefits. Of course, you may want to perform multiple exercises or multiple types of activities depending on your injury, but it would still represent a minimal time investment, certainly when in comparison to a full training load.

Now, if you’re an endurance-based athlete, you might be quick to dismiss these findings as irrelevant because you’re not much interested in muscle strength and size. However, that’s a foolish outlook. First of all, regardless of your event, muscle strength and size do matter. While you may not be looking for giant muscles, any loss of muscle size due to disuse will need to be re-gained, so you might as well prevent that loss. Secondly, consider the concept demonstrated- continuing to exercise the unaffected limb allowed for a reduction in loss of the immobilized limb. While strength training was the stimulus in this study, it stands to reason that a similar result could be possible with endurance training as well. It may be that the magnitude of the effect is less, but as demonstrated above, any benefit is worth the effort.

Reference

1. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2023 Feb 20. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000003140. Online ahead of print

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.