You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Injury risk in athletes: mind how you go!

Can psychological stress be a significant risk factor for injury? Sports Performance Bulletin looks at some fascinating research

It’s a fairly well accepted fact that some athletes seem to be particularly injury prone, whereas others are rarely injured. In years gone by, there have been a variety of explanations for this kind of observation; perhaps athletes with a more extrovert and aggressive personality are more likely to take risks in training and ignore the signs of fatigue and overtraining? Or maybe athletes who are more thoughtful and introverted tend to be more focused when engaging in sport, which reduces the risk of unwanted disruption in concentration or attention leading to poor movement patterns and subsequent injury.Personality and injury risk

One of the earliest studies into this topic took place nearly 30 years ago and looked at the link between ‘life stress’ factors and subsequent injury risk in American football players(1). One hundred and four players were monitored for injury occurrence for a year while a simultaneous record was made of life changes – both positive and negative – for each player. The results showed that compared to non-injured players, the players who had incurred a significant time-loss injury had experienced greater negative (but not positive) life changes in the previous twelve months. But how much of this injury risk is due to the events, and how much due to the way an athlete perceives and handles life events?Research on this topic ascribes major importance to the role of personality traits as a risk factor in sports injury(2-4). The thinking goes something like this: an athlete with an ‘anxious’ personality is more likely to perceive the rough and tumble situations of life in a threatening way. Combine this with poor coping resources (eg inadequate social support) and that athlete is more likely to experience a negative stress response and consequently become more prone to athletic injury. Although the relationship between stress and injury is complex, a 1990 study that looked at 452 athletes did indeed show that athletes with more life stress, little social support and poor coping skills were associated with more days of non-participation due to athletic injury(5).

However, although personality may be a factor in injury risk among athletes, the relationship is by no means clear. It’s likely that the truth probably lies somewhere in between – ie although a personality profile that characterizes the 'injury-prone' athlete is unlikely to exist, there are certain patterns and trends linked to personality that might be influential in determining overall injury risk. One early study illustrating this connection looked at the personality of injured college students majoring in gymnastics(6). It found that injured college gymnasts were scored as having higher levels of emotional instability, emotional disturbance, stress proneness and lack of self-control. However, a more detailed look at the data showed that these personality characteristics appear to either buffer or exacerbate the stress response, which is proposed to be the prime mechanism linked to injury. In other words, if personality is linked to injury, it’s very likely via indirect means.

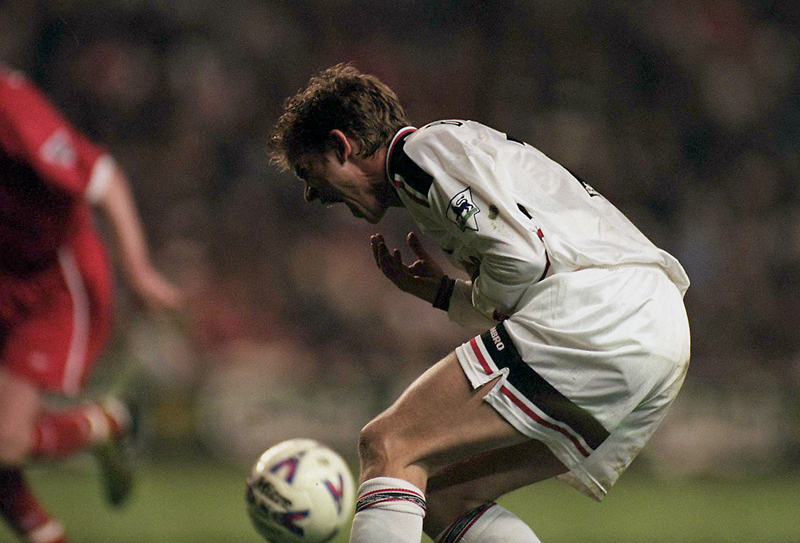

Footballers, psychological stress and injury

How strong is the link between psychological factors and injury, and how can this information be deployed to help sportsmen and women stay injury free? A 2010 study looked into the relationship between psychological factors and the prospective risk of injury in Swedish footballers and makes for fascinating reading(7), not least because footballers are among the most injury prone athletes with an estimated injury rate of 17-24 injuries per 1000 playing hours(8). Nineteen per cent of all sports injuries that occur in the Netherlands are due to football(9) and in Britain alone, the cost of treatment and time lost from work due to football injuries is estimated to be around £1 billion per year(8)!The study set out to examine the relationship between injury risk and (a) personality factors, b) coping variables, and (c) daily hassles among adult male footballers. Unlike some previous studies, the subjects in this study were adults rather than juniors so the complicating issues arising from adolescents undergoing a sensitive psychosocial developmental phase, with less developed coping skills were absent in this study. Forty eight male soccer players (aged from 16-36 years) competing on three different teams at a competitive level in Swedish divisions 4 – 6 and who had been playing soccer regularly for approximately 10-12 years were involved in the study. The players practiced 2-3 times a week and played weekly games from April to October. The researchers collected data from the footballers for a 4-month period. As well as recording injury rates, the researchers carried out five different types of psychological assessment – see panel 1 below for further details.

Panel 1: Psychological tests to evaluate injury risk in footballers

There are a number of tests used to measure psychological stress in athletes and in most cases, more than one will be applied. The tests used in the study on Swedish footballers were as follows:Football Worry Scale - The Football Worry Scale was used to measure competitive worry, including ‘fear of negative social evaluation’, ‘fear of failure’, ‘fear of injury or physical danger’ and ‘fear of the unknown’.

Swedish Universities Scales of Personality - Among the key characteristics assessed are anxiety, mistrust, stress susceptibility, submission, impulsiveness, adventure seeking, detachment, social desirability, embitterment, trait irritability, verbal trait aggression and physical trait aggression (see figure 1 for an example).

Life Events Survey for Collegiate Athletes – Determines three categories of events: negative life-event stress, positive life-event stress and total life-event stress.

Daily Hassles Scale - The Daily Hassles Scale is used to measure an athlete’s level of daily hassles. The test consists of 53 items addressing potential daily hassles.

Brief COPE - Brief COPE is used to measure an athlete’s coping skills and how they cope with stressors. Examples of coping skills include self blame, self-distraction, active coping, denial, substance use, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support, behavioral disengagement, venting, positive reframing, planning, humor, acceptance and religion.

Figure 1: Characteristics scored in the Swedish Universities Scales of Personality

The key findings were as follows:

- When the results were analysed category by category, the injured players had a significantly higher level of somatic trait anxiety, psychic trait anxiety, stress susceptibility and trait irritability. Indeed, stress susceptibility seemed to explain around 10% of the total variance between injured and non-injured players.

- Compared to non-injured players, analysis showed that the injured players had a significantly higher level of behavioral disengagement and self blame. A further analysis showed that the predictors of ‘acceptance’ and ‘self-blame’ could explain 14.6% of the total injury variance.

- Over the four months as a whole, the daily hassle score didn’t seem to be different between the injured and non-injured footballers. However, further analysis showed that the injured footballers had experienced a higher level of daily hassles before the onset of injury than the non-injured footballers – see figure 2.

Figure 2: The link between ‘daily hassle’ score and injury rate(7)

A comparison of the average daily hassle score (simple numerical scale) for the injured and non-injured footballers.

The researchers concluded that there were a number of significant psychological predictors that increase the injury risk among adult footballers. The main implication for both athletes and coaches is to be aware of these predictors and their impact on injury risk in order to prevent sport injuries. Interestingly, the same researchers followed up this study with a study on 108 junior footballers in SW Sweden the following year using the same kind of methodology(10). Injury records were was collected by athletic trainers at the schools over an 8-month period, and the results suggested four significant predictors that together could explain 23% of injury occurrence:

- Life event stress

- Somatic trait anxiety (anxiety that results in physical manifestations such as an increased heart rate. ventilation rate, and sweating etc.

- Mistrust

- Ineffective coping

Triathlon injury and stress

It’s not just footballers who have been under the spotlight regarding psychological stress and injury; another study into well-trained triathletes came up with interesting results(12). In the study, 30 triathletes were monitored weekly for signs and symptoms of injury or illness both during pre-season training and until the end of the competitive season 45 weeks later. As you might expect, the signs and symptoms of injury and illness were significantly associated with increases in training load. What was surprising however was that the greatest negative impact was produced not by training loads but by psychological stressors. Triathletes who had high scores for psychological stressors were more likely to become injured, more likely to have disturbed mood and were also more like to suffer from burnout.Summary and practical applications

The research is fairly unambiguous – psychological stress is a major risk factor for a subsequent injury. In particular, it seems that life stresses and ‘daily hassles’ outside the control of individuals are particularly associated with an increased injury risk. The evidence on the role of personality is somewhat mixed; while there seem to be some personality traits that could increase the degree of perceived stress, our understanding to date indicates that in most sports, personality is not fundamentally associated with injury risk.Given the above, there’s good news and bad news; the bad news is that without addressing the psychological needs of the athlete, injury risk is substantially increased. The good news is that because the key psychological stressors do not appear to be rooted in an athlete’s personality traits, there are practical steps that can be taken by all athletes and their coaches to reduce stress and (hopefully) decrease injury risk.

Practical advice for those with athletes in their care

Psychological stress can have serious implications for athletes seeking to avoid injury. For this reason, athletes and those who coach or care for athletes should bear in mind the following:- Personality is just one aspect of a complex interaction between an athlete’s history of stressors (eg life events, daily hassles, and previous injuries) and his or her psychological coping responses (eg coping strategies, social support, and mental skills). Therefore, simply labeling athletes by personality may do more harm than good. Be aware however that some psychological traits such as high trait anxiety, sensation seeking, ‘Type A’ behavior and single-mindedness are associated with an increased occurrence of sport injuries;

- Coaches who place considerable stress on athletes can increase the likelihood of injury, especially if they foster an environment where injured athletes feel worthless; this is because athletes will be more likely to hide aches and pains, thus increasing the likelihood of a subsequent injury;

- All athletes should understand that the nature of participation in sport means that at some point in time, injury is very likely to occur. However, instead of stressing the inherent risks associated with sport, the focus should be on doing those things that can minimize the chances of injury such as making certain the athlete is fit, practicing safe sport techniques, and very importantly, learning to recognize when their body is telling them that something is wrong;

- Injury prevention includes dealing with both psychological and physiological attributes of the athlete. The athlete who enters a contest while angry, frustrated, or discouraged or while suffering from some other emotional disturbance is more prone to injury than is one who is better adjusted emotionally. Coaches and carers should therefore develop the necessary counselling skills to confront an athlete’s fears, frustrations and daily crises, try to help where possible and know when to refer individuals with serious emotional problems to appropriate professionals;

- Coaches and carers should proactively work with athletes to help them develop practical solutions for managing and reducing the stresses and strains of their day-to-day life wherever possible – eg a better social support network, improved time management skills, low-hassle transport solutions, better sleep patterns, quality relaxation time etc.

References

- J Human Stress. 1983 Dec;9(4):11-6

- Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 1998; 10, 5-25

- American Journal of Sports Medicine 2000; 28, 10-15

- Scand J Med Sci Sports 2011 Feb;21(1):129-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01057

- Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1990; 58(2), 360-369

- Journal of Shanghai Physical Education Institute 1997; 21(1), 37-41

- Journal of Sports Science and Medicine (2010) 9, 347-352

- Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:354-9

- Injury Prevention. 2011;17(2):1-5

- Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011 Feb;21(1):129-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01057.x

- J Sport Rehabil. 2012 Mar 2. [Epub ahead of print]

- J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2010 Dec;50(4):475-85

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.