You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

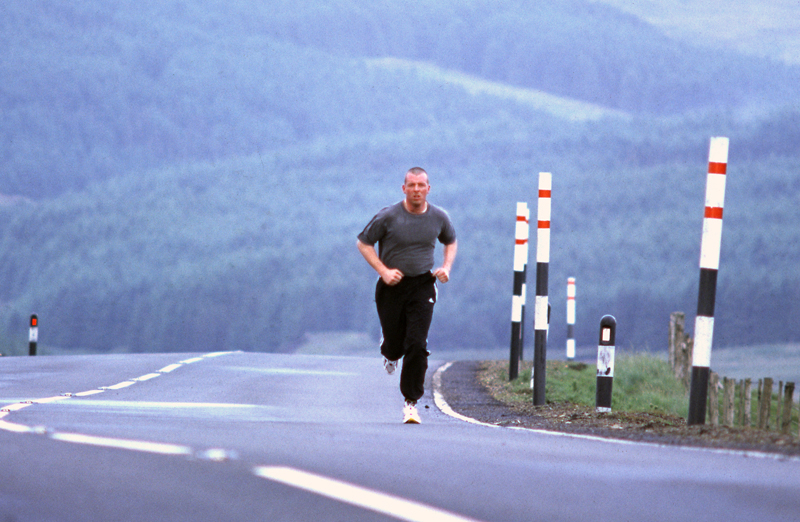

Novice runners: can strength training reduce injury risk?

SPB looks at new research on novice runners, and whether substituting in some strength training could help reduce the risk of developing a running injury

Everyone knows that running is good for cardiovascular health and weight management, but while some runners train to compete in race situations, the data shows that many more runners are recreational - running mainly for health and fun, often completing just a few kilometres per training session(1). However, despite the health benefits that running brings, there is a something of a fly in the running ointment – and that something is the risk of a running-related injury (RRI).

Although the risk of an RRI varies greatly according to the anthropometrics and biomechanics of any individual runner, numerous studies show that it is very significant. For example, in a 6-month study of 87 recreational runners, 79% of the runners suffered at least one lower limb injury during the observation period(2). In another study of 583 habitual recreational runners, researchers found that over the 12-month observation period, 252 men (52%) and 48 women (49%) reported at least one lower-limb injury that was severe enough to affect running habits, resulting in a visit to a health professional, or requiring the use of medication(3). Among the wider running population as a whole, research suggests that the risk of sustaining a lower-limb injury can be anything from one injury per 147 hours of training to as high as one injury per 17 hours of training(1)!

RRI risk for novices

Within the spectrum of recreational runners, novice runners (runners with less than six month’s running background) seem to be at particular risk of injury. But why is this? Once again, the risk for each novice runner is highly variable, but research suggests that taken as a whole, novice runners face particular challenges(4,5):

· Novice runners are often heavier (many start running to lose weight), which combined with relative leg muscle weaknesses and imbalances, excessive or insufficient flexibility in joints and muscles etc increases the risk of an RRI.

· Novices are much more likely to make errors in their training approach (eg an excessive training volume and/or load, insufficient recovery, a training load that increases too rapidly etc).

· Novices lack the prior training experience of running, and are therefore less ‘tuned in’ to their body (for example being aware of when to back off).

Another important reason for the increased risk of an RRI in novices is that the body’s structural elements, like bones and tendons, are MUCH slower to adapt to training loading than the body’s cardiovascular and circulatory system. Human tendons and connective tissues require many weeks to adapt to increased training loads while bone requires months to adapt (by becoming stronger and denser)(6). In other words while the aerobic fitness and endurance capacity of a would-be distance runner improves fairly rapidly in response to training, the athlete’s structural integrity lags well behind when it comes to adaptation.

Novice injury avoidance strategies

Given the risk of an RRI is elevated for novice runners, what steps can be taken to minimize injury? The most obvious place to start is to try to address the particular challenges that novice runners face (outlined above). Of these, the easiest place to start is to structure any training program properly, and in particular, to try and avoid the main training error that afflicts inexperienced runners – too rapid an increase in the any or all of the following: training volume, training intensity, incorporation of hill training, and the maximum duration of runs(7-9).

Are there any practical strategies that could help compensate for the slower training adaptations in ligaments, bone and tendons, and which lag behind the cardiovascular and muscular adaptations? One such possibility might the incorporation of some strength training into a novice program. In more experienced runners, adding some lower-body strength training is known to enhance running efficiency and performance(10-13). But could some novice strength training help prevent injury?

Strength training and injury risk

In team sports such as soccer, rugby, basketball etc, the incorporation of strength training has been shown to reduce injury incidence(14). In runners however, the evidence for strength training reducing injury risk is far less clear cut. For example, in one study, a group of experienced runners who performed additional strength training for eight weeks (with an emphasis on foot-strengthening work) experienced a 2.4-fold reduction in RRIs(15). By contrast, the addition of a 12-week strength program during a period of marathon training produced no injury-reduction benefits whatsoever(16).

The uncertainty as to whether strength training can reduce injury risk in novice runners is compounded by the fact that none of the research to date has specifically looked at novice runners, and also because in the studies that have been carried out, the strength training has generally been prescribed in addition to (rather than replacing part of) an existing running program. For novice runners who are trying to build structural integrity, reducing the volume of running training and replacing it with some strength work might be worthwhile; simply adding it on top of a running program is likely to be too much!

New research

To try and clarify whether novice runners might benefit from reducing their running training program slightly, instead adding in some strength work, a team of French and Belgium scientists have just published a study on this very topic(17). Published in the journal ‘Sports’, this study looked at 76 young novice runners to see if substituting a portion of their running training with strength training reduced the risk of injury, and whether this strategy impacted running performance (either positively or negatively).

Thirty eight female and thirty four male, novice runners were recruited from a university setting to participate in the study. All runners had to meet the following criteria:

· Between 18 and 30 years old.

· Matched the study definition of novice runners (defined as someone who has not been running more than once a week for more than six months).

· Had not sustained a musculoskeletal injury in the past six months.

Once recruited, the novice runners were randomly allocated to one of two groups:

· Running only - A 21-week running only program.

· Running + strength - A 21-week running program where around 25 minutes per week of running training was instead replaced with a mixture of dynamic and static body strength exercises.

Each week, two sessions of one hour were supervised, and one mandatory unsupervised session of 30 min was completed by the participants. The supervised sessions took place in the evening on an indoor track, whereas the unsupervised sessions took place at any time on a treadmill or outside.

The running-only group received a standard running program exclusively composed of supervised running sessions. The training sessions were composed of running and recovery (walking or slow running) periods. The running + strength group performed strengthening exercises, which replaced a little of the running volume. Strength training was performed exclusively with body weight and consisted of exercises such as squats, deadlifts, hip thrusts, and step ups or downs, planks. Importantly, the total training volume was exactly the same in both groups, meaning that the time allocated to strength training in the running + strength group was matched by the reduction in time spent running training.

What they found

As well as looking for the rates of injury in the two groups, the researchers also recorded dropout/attrition rates for other reasons – eg lack of motivation, boredom etc. The runners in the two groups were also assessed for maximal aerobic capacity using a shuttle test – to see if the addition of strength training had impacted the cardiovascular fitness gains made by the runners.

When it came to the results, the first finding was that attrition rates were higher in the strength + running group than in the running-only group (52.6% vs. 41.7% respectively). Secondly statistical analysis showed that the gains in aerobic capacity were the same in both groups. Most importantly (in terms of the main goal of the study), 11 runners out of the thirty-nine participants who completed the study (ie made it to the end of the 21-week intervention) reported having an RRI.

Of these, eight runners reported an RRI in the running-only group (38%). These included one case of non-identified glute (buttock) muscle pain, one case of patellofemoral (knee) pain syndrome, one case of ilio-tibial band syndrome, two cases of medial tibial stress syndromes (shin splints), and three cases of calf or tibial pain. Three runners reported an RRI in the running + strength group (16.6%); one case of greater trochanteric (hip) pain syndrome, and two with patellar (knee) tendon pain. However, despite there being eight injuries in the running-only group compared to three in the running +strength group, a statistical analysis showed that this difference wasn’t large enough to be meaningful (ie the result could well have arisen by chance, and a larger study would be needed to confirm any benefits).

Practical implications for novice runners

Overall, we can conclude from this study that for novice runners, replacing a portion of running training with strength training doesn’t seem to offer any significant benefits. It’s true that the running + strength group did suffer a lower rate of RRI, but the difference was not statistically significant. One possible reason for this inconclusive result could be that the strength exercises performed were not running-specific or focussed enough. More research is definitely needed!

That the addition of strength did not reduce the dropout rate rates also surprised the researchers somewhat since previous research has identified that training programs with more variety tend to improve adherence rates(18). One explanation here is that as all the participants were novices, they most likely were not practitioners of strength training, and therefore may have found the higher-intensity nature of the strength sessions more demanding, with more post-exercise muscle soreness than when just running.

Overall, the evidence favoring substituting in some strength training to a novice running program is not robust enough to recommend this approach. In simple terms, allowing the body of a novice runner to acclimatize to the demands of running by performing running is likely to be enough in the first instance. Strength training instead may be better left until six months or so of running experience is under the belt. In the meantime, novice runners should be sure to avoid too rapidly increasing training volume, training intensity, incorporation of hill training, and the maximum duration of runs in order to stay injury free!

References

1. J Physiotherapy 2013; 59(4) 263-269

2. Br J Sports Med . 2004 Oct;38(5):576-80

3. Arch Intern Med. 1989 149(11):2565-8

4. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2005 Aug; 16(3):651-67, vi

5. Sports Med. 2014 Aug; 44(8):1153-63

6. J Appl Phys 1992; 73(3):1165-1170

7. J. Athl. Train. 2022, 57, 650–671

8. J. Physiother. 2013, 59, 263–269

9. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 869–886

10. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1117–1149

11. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 545–554

12. Int. J. Sports Med. 2009, 30, 27–32

13. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999, 86, 1527–1533

14. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 871–877

15. Phys. Ther. Sport 2020, 42, 107–115

16. Sports Health 2020, 12, 74–79

17. Sports (Basel). 2024 Jan 9;12(1):25. doi: 10.3390/sports12010025

18. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2014 Oct;36(5):516-27

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.