Stretch your horizons with PNF!

What is PNF stretching, what benefits can it bring, and how should it be performed? SPB looks at the evidence

No matter how carefully constructed your training program, there will inevitably be times when you seem to reach a plateau or ceiling in your performance. That’s the time when strength athletes can employ advanced routines such as supersets, negative reps and pre-exhaustion techniques, and aerobic athletes can turn to things high-intensity intervals training to push their performance envelope that bit further. But what if your sport involves - and benefits from - increased range of movement? Or, what if you’re attempting to improve your flexibility to stave off an old injury? What kind of advance stretching options can you deploy to lift your performance just a little bit more? That’s the time when you need to pull something special out of the toolbox, and an excellent weapon is a stretching technique known as ‘proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation’, or PNF for short.What is PNF?

Apart from being a real mouthful, especially after a couple of beers, PNF is a stretching technique that can produce significant gains in flexibility, thereby also improving resistance to injury and re-injury. Research shows that not only do athletes require adequate joint range of movement to move effectively without inducing injury(1), but also that larger movement ranges of the lower-limbs are associated with reduced risk muscle strain injuries during competition(2).In general terms, PNF stretching involves a static stretch of a muscle in the normal way, followed by a contraction of that muscle against an immovable object - such as a partner - for around 10-15 seconds followed by another stretch - during which your partner helps you ease into a slightly deeper stretch. The theory is that this type of contraction stimulates the ‘Golgi’s tendon organ’, which then causes an ‘inverse stretch reflex’. In plain English this means that the stretched muscle is able to relax just a little further.

However, some researchers believe that these muscle stretch reflexes following a contraction of a stretched muscle are not due to the activation of Golgi tendon organs, but instead may be due to a phenomenon known as ‘pre-synaptic inhibition’ of the muscle spindle sensory signal(3). Regardless, after this type of contraction, the muscle can be stretched a little further statically than before the contraction took place. There are two PNF techniques that are popular: the contract-relax method and the contract-relax-antagonist-contract method. The contract-relax stretching (as described above) is considered as a particularly safe and effective stretching technique(4).

Why it works

PNF stretching is not new. It was the brainchild of Herman Kabat who first starting using the technique back in the 1940s for the rehabilitation of injured muscles(5). Although the process is not fully understood, it is believed to work through two processes: irradiation where a spread of neuromuscular excitation takes place through a synergistic muscular contraction and successive induction, where an enhanced effort in one muscle can occur after its opposite partner has been contracted. If why it works is still unclear, that it works is not open to question. The gains in flexibility that can be achieved with PNF are well documented, and studies have demonstrated that over an extended period, a program of PNF stretching can produce significantly greater flexibility gains that can be achieved either with static or ballistic stretching(6,7).In practice

The sequence of static stretch then a contraction against immovable resistance then another static stretch can be repeated more than once for a cumulative effect. For example, suppose you wanted to work (with a partner) on improving range of movement in your hamstrings (a commonly tight muscle group, and one prone to injury) using PNF:- To get the initial stretch, you would lie on the floor on your back, while your partner raises the leg (in a straight position) to be stretched into the air, keeping the other leg flat on the floor, until you feel a comfortable stretch in the raised leg. This is the static stretch.

- After 20 seconds or so, with your leg still in this position, you would gradually push harder and harder against you partner as if you were trying to return the outstretched leg back to the floor. Your partner however would resist this force, keeping your leg static – this is the isometric contraction, which should be held for 15-30 seconds.

- After this time, you stop pushing and relax. Now is when the inverse stretch reflex kicks in and your hamstrings relax. If your partner applies a bit more leverage, you’ll find that you can easily move into a deeper stretch without any discomfort.

- After holding this new and deeper stretch for 20 seconds you can begin the next cycle and start another isometric contraction.

PNF for singles

If you can’t press gang a friend or spouse to help you out with a bit of PNF stretching, don’t worry. While partner stretching is still the best option, you can adapt your normal static stretches to incorporate some PNF. For example, in the hamstring stretch given as an example above, you can wrap a towel over the foot of the up-stretched leg to generate the initial static stretch. Then for the contraction, you can hold the towel under enough tension to hold the leg static while you apply an isometric contraction during which you apply force as if to return the leg back down to the floor. When you relax again, use the towel to draw the leg a little further back into a deeper static stretch.There are a number of other basic stretches that can be adapted in this way. For example, you can lie face down and pull the ankle towards the buttock to stretch the quadriceps muscles of the front of the thigh. Once you’ve stretched statically, you can generate an isometric contraction by trying to straighten your leg while holding the ankle firmly. Whichever muscle group you want to give the PNF treatment to, all you need to be able to do is apply a contraction while holding the limb still in the statically contracted position then move to a slightly deeper stretch. However, before you get too carried away with PNF stretching, bear in mind that it can be quite intense and shouldn’t be performed when you are tired and stiff from a previous workout or without a thorough warm-up first. To get the best out of PNF stretching, you should follow the guidelines set out in box 1 below.

Box 1: PNF stretching guidelines

- Only attempt PNF stretching after a thorough whole body warm-up.

- When pushing against resistance in the isometric contraction phase, build up the effort smoothly and slowly for the first two seconds and then maintain this effort for the remaining contraction.

- Never try to use an explosive movement in the contraction phase – use an isometric (static) contraction.

- If you’re using a partner, he or she should only provide enough resistance for you to push against so you remain static in the contraction phase. During the stretching phase, he or she should only be providing mild assistance to ease you into a deeper stretch.

- Two or three cycles of static stretch/isometric contraction/static stretch are ample.

- Avoid over-stretching – watch out for feelings of tension or mild pain that become greater, the longer the stretch is held. Watch out also for vibrating or quivering of the muscles – another sign of possible over-stretching.

New research on PNF

While robust evidence gathered over an extended period of time suggests that PNF is an excellent way to develop increased range of movement, very recent evidence indicates there might be other benefits too, and one of these involves balance. An important component of balance control is the sensory information gained from muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs; if PNF stretching can activate the Golgi feedback system, this in turn could improve the ability to detect and respond promptly to changes of an unstable environment.In a 2018 study, researchers investigated the effects of a single dose of contract-relax PNF stretching of the hip adductor and abductor muscle on lateral dynamic balance(8). The hip adductor/abductor muscles were studied since they are responsible for maintaining lateral balance(9), which is of particular interest not only to athletes, but also to the wider population since this aspect of balance is known to steadily decline with aging(10).

Forty five young healthy participants (age 19–23 years) were assigned either to the intervention group or the control group. Balance testing was carried out before and immediately after contract-relax PNF stretching in the intervention group or after a passive 5-minute rest in the control group. In the PNF group, the participants performed three cycles of contract-relax PNF stretching, targeting the adductor and abductor muscles of the hip. Balance was assessed by measuring the participants’ responses when stood upon an electronic oscillating balance board.

The results showed that in the PNF stretching group, all the measured variables relating to the body’s dynamic balance were significantly improved immediately after the stretching. This included the degree of sway away from vertical induced by the balance board, the total time accumulated in a non-vertical position and reaction times to correct sway. In the control group however, there were no such improvements. The authors’ conclusion was that just one session of PNF single dose hip adductor and abductor muscle stretching can improve lateral dynamic balance – a conclusion that could be relevant to athletes whose sports require high levels of agility and balance.

PNF for strength work?

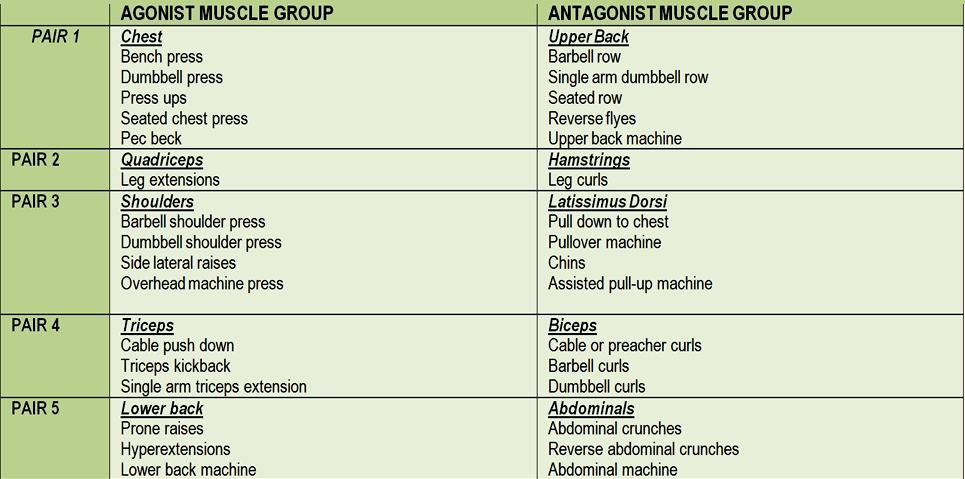

Over the last decade, there’s been a growing interest in the practice of using PNF stretching between strength-training sets in order to increase muscle activation and increase the number of reps performed(11,12). However, in this technique, it is not the muscle being worked that is PNF stretched but the antagonist muscle (the opposite muscle that produces the reverse movement – see table 1). So for example, an athlete working on the quadriceps muscles of the frontal thigh would perform PNF stretches on the agonist hamstring muscles in between each set for the quadriceps.TABLE 1: AGONIST/ANTAGONIST MUSCLE GROUPS AND TRAINING EXERCISES

However, not all studies have found a benefit; in a study by Brazilian researchers for example, 10-second PNF stretches of the antagonist muscles (pectorals of chest) produced no gains in agonist muscle (upper back) performance during the seated row exercise(13). But now a brand new study seems to add clarity to the best PNF protocol to produce a beneficial effect(14).

Fourteen physically active individuals participated in this study, which was designed to investigate the effect of different numbers of inter-set PNF stretches for the antagonists (hamstrings) on the total number of repetitions completed for the agonists (quadriceps) in the leg extension exercise. All the participants performed the following experimental protocols in randomized order on three different days:

- Traditional - without PNF stretching before subsequent execution of the leg extension exercise.

- Shorter PNF - with 3 x stretches of 20 seconds under tension for the stretch and subsequent execution of the leg extension exercise.

- Longer PNF - with 3 x stretches of 30 seconds under tension for the stretch and subsequent execution of the leg extension exercise.

What they found

When the number of reps were tallied, the results showed that there was a significant increase in the average total number of repetitions for the longer protocol compared to the traditional protocol (see figure 1). In the shorter PNF protocol, more reps were also completed but the increase wasn’t quite large enough to be considered statistically significant. The conclusion therefore was that hamstrings PNF stretches of 30 seconds duration were effective for promoting greater contractile performance for the quadriceps muscles.Figure 1: Total reps in leg extension with short and long PNF vs. none

Significantly more leg extension reps were completed with long (30-second) PNF stretches of the hamstrings compared to traditional (no inter-set PNF) training.

Using this information

Athletes who need to work on increasing their range of movement to enhance performance or those where there’s a need to improve muscle flexibility to rehabilitate/prevent muscle injury should consider the use of PNF stretching. This is particularly true if other types of stretching aren’t producing the gains needed.More generally however, there’s new evidence emerging that athletes can harness the muscle stretch-reflex produced by PNF to enhance balance and agility – simply by performing some PNF stretching of the hip adductors/abductors prior to activity. In sports where high levels of balance and agility are required, a warm up that incorporates some PNF stretching should be considered. For athletes looking to build strength in a particular muscle group, there’s also good evidence that 30-second PNF stretches of the antagonist muscle group can deliver more reps and a therefore a greater training stimulus. Maybe it’s time to stretch your horizons?!

References

- Strength Cond. Res. 2010;24:2698–2704

- Strength Cond. Res. 2007;21:1155–1159

- Sports Biomech. 2004 Jan;3(1):159-83

- Journal of Human Kinetics. 2012;31:105–113

- Aust J Physiother. 1966 Aug;12(2):57-61

- Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1982 Jun;63(6):261-3

- J Strength Cond Res. 2003 Aug;17(3):489-92

- 2018; 6: e6108

- Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2010;24:1888–1894

- Age and Ageing. 2006;35:ii7–ii11

- J Exerc Physiol. 2012;15(6):11–25

- ConScientiae saúde. 2014;13(2):252–258

- Braz J Sci Mov. 2013;21(2):71–81

- Int J Exerc Sci. 2022; 15(4): 498–506

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.