You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Gluteal tendinopathy: a pain in the butt

Gluteus medius and minimus tendinopathy are painful and debilitating disorders in athletes. SPB looks at the diagnosis and rehab options for this type of injury...

No matter how good the general condition of an athlete, the fact is that there are times when the biomechanical demands of his or her sport exceeds the ability to control motion and the stability throughout the kinetic chain of the muscles and joints used to execute that movement. For example, consider a javelin thrower; when the athlete releases the javelin with explosive force, the muscules of the lead hip need to resist considerable forces in all three planes of motion. If any weakness exists in any plane of movement, the kinetic chain can be destabilized, and injury may be the result.

One problematic condition for athletes that can arise from this and similar scenarios is something called ‘gluteal tendinopathy(either gluteus medius or gluteus minimum). The combination of overuse and underlying weakness of the gluteus medius and minimis –two key buttock muscles - can cause strain, tearing, or degeneration of these muscles or their respective tendons, inducing tendinopathy (tendon inflammation) in the athlete.

Understanding hip and buttock anatomy

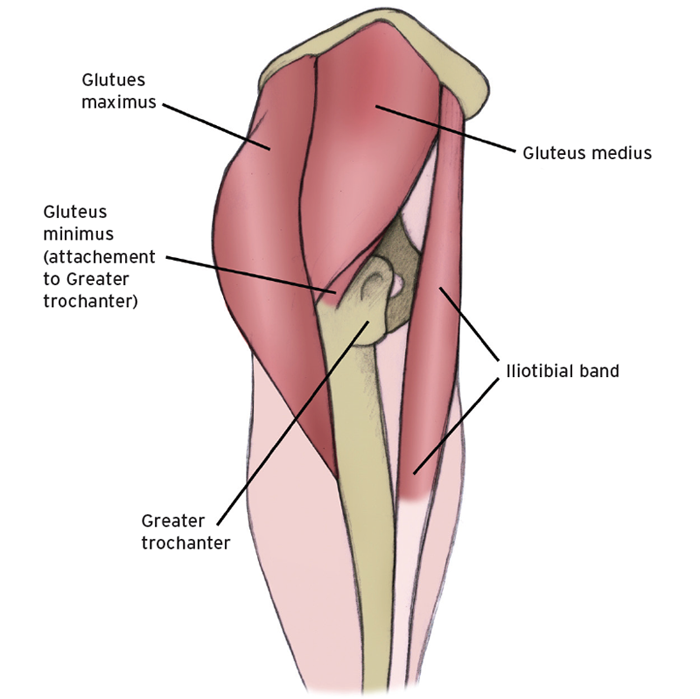

A schematic view of gluteus medius and minimus can be seen in figure 1 below. The gluteus medius muscle originates iliac crest region of the pelvis and crosses over the greater trochanter (the bony projection at the top of the femur). Gluteus medius is a primary hip abductor, which means it moves the leg outwards and away from the center line of the body. Its frontal fibres rotate the hip inwards, while the rear fibers assist in outwards rotation. In weight bearing positions, these muscles help keep the pelvis from dropping to one side.

Gluteus minmus meanwhile is a fan-shaped muscle underneath the gluteus medius muscle, and which stretches from the same area of the pelvis, but attaches instead to the outside of the trochanter. Gluteus minimus (in association with other muscles) primarily abducts the hip when the hip is in extension (ie the thigh is lined up with the upper body), and another key function of this muscle is to help stabilise the ball-shaped head of the femur in the hip socket of the pelvis (acetabulum) when an individual is walking.

Figure 1: A schematic representation of gluteus medius and minimus

What are the symptoms of gluteal tendinopathy?

Athletes who develop gluteal tendinopathy tend to experience lateral hip pain at the point where these gluteal muscles insert onto greater trochanter of the femur(1). Typically patients complain of a ‘dull and achy’ lateral hip pain, which is aggravated by weight bearing and abduction movements under loading. Although it can be hard to distinguish, medius tendinopathy often presents as tenderness more to the rear of the hip, whereas pain that present in a more frontal position suggests the problems are more likely to be attributed to gluteus minimus.

In some patients however, symptoms of gluteal tendinopathy may present in an atypical fashion, masquerading as other disorders, which in turn can lead to misdiagnosis and mismanagement of the condition. This is partly because the typical anatomical descriptions of the gluteus minimus (as shown in figure 1) are not always accurate. Also, pain that originates from the gluteus minimus can be severe and its source is relatively hidden; this pain may be felt at the in the lateral areas of lower limb, as far down as the outer ankle(!) and also up into the buttock, imitating sciatica(2). Moreover, when a physio tries to press and feel for the ‘trigger point’ (source of pain), this is not always easy due to the minimus lying under gluteus medius.

Box 1: Gluteal tendinopathy in runners

In the absence of direct trauma, when runners start to experience pain over the lateral hip, it is most likely to be due to gluteal tendinopathy. This develops in a manner analogous to that of shoulder bursitis conditions and rotator cuff tendinopathies(3). It has been suggested by some authors that tension in the iliotibial band may result in frictional trauma to the gluteus medius and minimus tendons(4). This trauma has been speculated to occur due to weakness in the hip abductor muscles during weight bearing.

For example, when the gluteus minimus becomes fatigued and the pelvis is allowed to shift into a sideways horizontal movement, which causes more tension develops in the iliotibial tract, in turn causing compression and friction on the gluteal tendons. This dysfunctional running gait leads to the onset of pain. And while origin of the pain orioginates from the gluteal tendons, it may disguise itself as low back pain, pain within the hip joint itself or pain in the sacroiliac region of the pelvis.

Diagnosing gluteal tendinopathy

If you develop lateral hip pain with no obvious cause and seek advice from a physio, he she will initially carry out a detailed evaluation. This approach will involve taking a thorough history, an inspection of your hip, palpation (squeezing motions around the joint to feel for anomalies), and assessments of your range of motion, stability, and strength in all planes of motion around the hip. He/she will also be interested in checking out other regions and joints around the hip area (eg sacroiliac joint and lumbar spine). In addition, your walking/running gait patterns should be observed, noting any leg length discrepancy and compensations due to weakness, as well as heel strike and avoidance patterns. If he/she suspects an avulsion (where a bit of bone has been pulled away from the tendon insertion point), you will almost certainly be referred for an MRI scan and/or ultrasound imaging.

Unfortunately for your physio, there’s no definitive test to rule gluteal tendinopathy in or out. However, there are a number of different tests that they may ask you to carry out to help them make a diagnosis:

· Trendelenburg test - assesses the functional strength of gluteus medius. The patient stands unsupported on one leg. If the pelvis tilts towards the unsupported leg, this indicates abductor weakness on the stance leg.

· Ober’s test – the patient lies on the unaffected hip. The symptomatic hip and knee are held in a flexed (bent) position. The hip is moved outwards and extended so that the iliotibial band of that leg lies over the greater trochanter. The patient then passively moves the hip and knee toward the start position. Pain during this process indicates a tight, contracted or inflamed fascial tissue and iliotibial band.

· Thomas test – the patient lies on his/her back and holds the unaffected leg in the knee-to-chest position while the affected leg is kept completely extended on the examination table. If the extended thigh is elevated off the table, the test is positive, indicating hip flexor tightness;

· Ely’s test – the patient lies in a face-down position, with the physio passively bending the knee and bringing the heel toward the buttock. If the heel cannot touch the buttocks, the hip of the tested side rises up from the table, or the patient feels pain or tingling in the back or legs, the test is positive indicating rectus femoris (a quadriceps muscle of the frontal thigh) tightness.

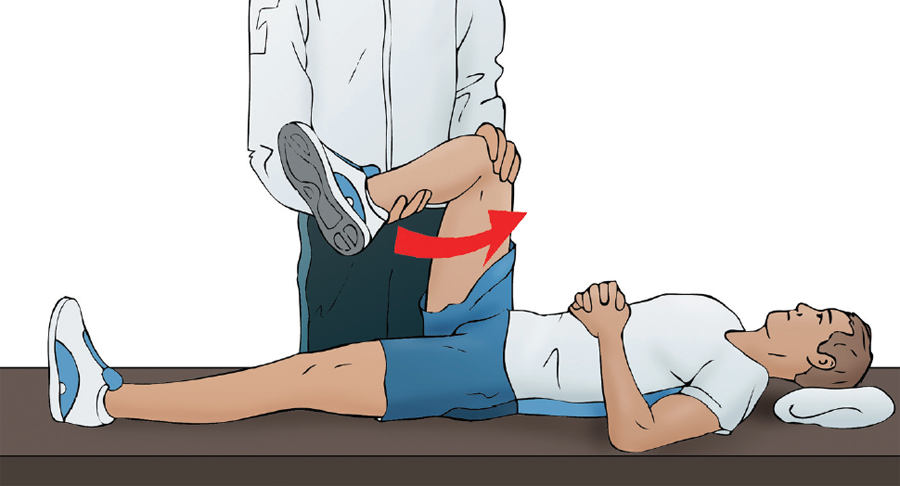

In addition, there are two further tests for which the diagnostic ability is considered high: the 30-second single leg stance test and the resisted external derotation test(5). In the single-leg stance test, the patient balances on one leg for 30 seconds with patient’s hands gently held by the physio to limit side-to-side trunk sway. If pain is experienced at any time point, the test is deemed positive. In the ‘external derotation’ test (see figure 2), the patient lies on their back with the hip flexed to 90 degrees and the lower limb rotated inwards to the onset of pain. The patient is then asked to actively return to neutral (external rotation) against the clinician’s resistance. Reproduction of pain is considered a positive test. Statistical analysis has shown excellent sensitivity and specificity, with 100% and 97.3%, respectively, for the single-leg stance test and 88% and 97.3%, respectively, for the resisted external derotation test, which makes them a excellent but simple diagnostic tool.

Figure 2: external derotation test

Treating and managing gluteal tendinopathy

As with all tendinopathies, the primary goal for athlete is firstly to reduce any pain and dysfunctional movement before progressing to therapeutic training using eccentric type exercise (where muscles are lengthening under load). Although no studies on the benefits of eccentric training have been carried out specifically on gluteal tendinopathy, there’s good scientific evidence in the literature for this rationale, where the treatment of the Achilles tendon, patellar tendon of the knee, and lateral epicondyle of the elbow are strongly supported(6,7). Assuming your physio is confident that the hip pain you’re suffering is due to gluteal tendinopathy, he/she will likely provide a staged program of treatment then rehab based on a 3-phase approach – an example of which is set out in table 1.

Table 1: Suggested rehab program for gluteal tendinopathy(8)

Phase 1 (Acute)

Goal: concentric hip abduction against gravity without pain.

· Rest, ice, compression and elevation for first 48 hours after injury (if traumatic)

· Massage, NSAIDs, TENS, ultrasound

· Pain‐free gluteal stretching (knee to opposite shoulder) and passive range of motion (PROM) exercises

· Non weight-bearing hip progressive resistive exercises (PREs) without weight

· Sub-maximal isometric contractions progressing to maximal isometric

· Therapist‐resisted knee extension, hip extension

· Diaphragm breathing

· Core stabilisation exercises (pelvic tilts etc.)

· Flexibility program for non-involved muscles

· Bilateral balance board

Phase 2 (Sub-acute)

Goal: Ability to perform pain free short-lever eccentric training

· Bicycling/Elliptical/StairMaster/Swimming

· Non weight-bearing hip PREs with added weight

· Bridges (bilateral progressing to single leg bridge)

· Quadruped hip extension, fire hydrants exercise

· Planks, side planks

· Weight‐bearing hip PREs (eg extension/abduction using a Theraband [TB]) or cable column (concentric to eccentric)

· TB squats, lateral walks

· Single limb, step down lunges (ie no push back upright) with reciprocal arm movements

· Eccentric short lever fall outs (see figure 3)

· Balance board squats

· General flexibility program

Phase 3 (Sports specific training)

Goal: pain-free sport specific activities

· Phase II exercises but with increased load, intensity, speed and volume

· Plank progression: prone plank + hip extension, side plank + abduction with eccentric resistance

· Standing resisted stride lengths on cable column

· Slide board

· Lunges (in all planes) with progressing balance challenges (eg using BOSU ball)

· Progressive balance exercises

· Standing hip eccentric resistance progressing* to standing hip eccentric resistance plus a single-leg squat

· Standing eccentric training using treadmill resistance**

· Plyometric sport specific training

· Correct or modified sport specific movements

*Standing eccentric training can be achieved with a Theraband around both feet stepping out to the uninvolved side, loading the involved limb, then slowly returning to the starting position. **Eccentric treadmill resistance is performed by resisting the belt of the treadmill as the leg comes from an abducted to an adducted position.

A particularly useful example of eccentric gluteal training is the ‘short lever supine fallout’. Here, the patient rolls towards the affected side then externally rotates the unaffected side, loading the affected side, then slowly resists the resistance band to the starting position (see figure 3). Table 1 shows a suggested 3-stage rehab plan based upon the principles outlined above.

Figure 3: Short lever supine fallout

In summary

Should you be unlucky enough to develop it, gluteal tendinopathy is a debilitating condition for an athlete and its diagnosis is not always straightforward. The good news however it that with the right treatment and management approach, you can expect to make a full recovery. This approach will require a thorough and stepwise evaluation in clinic by an experienced physiotherpaist, which includes relevant and appropriate tests to help provide the correct diagnosis. Once correctly diagnosed, an appropriate rehab program can begin. As with other tendinopathies, this should focus on the reduction of pain and dysfunction, followed by a progression to eccentric-based therapeutic training, the combination of which is likely to yield good results and enable you to return to sport with full functionality.

References

1. Clin J Sport Med. 2011;21(5):447-453

2. Movement, stability and low back pain. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. p.53-71

3. Eur Radiol. 2003; 13: 1339-1347

4. Surg Radiol Anat. 2004; 26: 433-446

5. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2008; 59(2) 241–246

6. Brit J of Sports Med. 2013;47(9):536-544

7. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(3):360-366

8. Int J Sports Phys Ther. Nov 2014; 9(6): 785–797

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.