You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Injury rehab: stretching the truth

Can static stretching help injured athletes regain their full pre-injury performance? SPB looks at brand new evidence

The role of stretching as a tool to improve athletic performance is not as straightforward as many athletes assume. Although it’s natural to assume that stretching is always a ‘good thing’, this assumption is not actually supported by the evidence. The reason it’s impossible to make a universal recommendation is that there are different kinds of stretching that can be performed, which have different physiological aims (see box 1). It also depends on how long the stretching routine is performed for and when it is performed in relation to exercise. For an overview of the most up-to-date thinking on this topic, readers are directed to this article.

Box 1: Common modes of stretching

The term stretching covers a number of different techniques for maintaining and developing flexibility. The four most common modalities are listed below:

- Dynamic range of motion stretching - often employed in warm ups where the major muscles are moved rhythmically in gentle repetitive motions within their full but normal range of movement.

- Static stretching –The muscles/joints are moved slowly and steadily into the stretch position and held static without bouncing, then released - widely acknowledged as a relatively safe technique for stretching novices and useful for increasing range of movement.

- Ballistic Stretching – an extension of dynamic stretching movement, where the muscle is taken to end of its range of motion then slightly over-stretched by ‘bouncing’. Only well-conditioned athletes, whose sport requires explosive and ballistic movements, are recommended to use this kind of stretching.

- Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) – a sophisticated technique combining static stretching with added resistance (usually provided by a partner) against which the stretched muscle group works. PNF can improve further flexibility in those already accustomed to static stretching.

Static stretching pros and cons

Probably the most commonly practiced stretching mode by athletes is static stretching. Static stretching can improve range of movement in the muscle-joint system, both immediately after stretching and in the longer term if practiced regularly(1). Given that a natural full range of movement is important for the optimal biomechanical functioning of joints and muscles, we might expect that static stretching is a great way to reduce injury risk and boost performance.

However, while it’s true that some studies have found static stretching reduces injury risk(2), not all studies have produced positive results. In particular, static stretching used as an injury prevention strategy for endurance athletes seems unable to reduce the prevalence of muscular–skeletal injuries(3). When it comes to performance benefits of static stretching, the evidence here is also pretty patchy – so patchy that the evidence actually leans toward negative effect – ie performance may be worsened by a bout of pre-exercise stretching!

For example, studies on static stretching have found that a single bout performed during a warm-up impairs running performance and running economy (how efficiently the muscles are able to use oxygen)(4,5) and reduces maximal strength and muscle power(6). In particular, it seems that when athletes perform static stretching routines, long-duration stretches held in excess of 60 seconds per muscle–tendon unit are most likely to cause performance impairments(7). For all the reasons given above, static stretching is less ‘fashionable’ as a training and performance tool than it once was because the assumption ‘it will always be doing some good’ has been debunked. But are we at risk of throwing the stretching baby out with the bathwater? Are there some circumstances where static stretching can definitely aid performance?

Injury rehab and functionality

One such set of circumstances could be when athletes are trying to regain full functional performance following an injury. When athletes return to sport following an injury, they need to be pain and symptom free(8). But it that enough? Muscles and joints not only need to be able to contract in a pain-free manner, but exert generate levels of force through the widest possible range of movement. In the early stages of injury recovery, early mobilization using gentle stretching has been shown to be beneficial for getting athletes on the road to rehab(9).

Unfortunately however, the commonly implemented rehabilitation programs using physiotherapy and mobilization often fail to fully restore muscular and athletic function. For example, a study on injured athletes found that despite being fully rehabilitated back into sport, even 11 years after an Achilles tendon rupture, the athletes demonstrated a 5% reduction in peak calf muscle torque compared to the uninjured leg(10).

Likewise, research demonstrated that athletes suffered a 5.5% deficit in muscle cross-sectional area even after ten weeks of a full blown rehabilitation program following injury(11). More generally, researchers have argued that time-extended and more comprehensive/intensive rehabilitation is required to fully restore muscular strength following injury and thus reduce muscular weaknesses and imbalances(12).

Could static stretching help?

It’s generally recommended that following an injury (especially a serious injury where surgery may be required) strength training should not be performed during the early phases of what could be a lengthy recovery. Unfortunately however, over a period of time, this can lead to muscular strength imbalances between the injured and non injured limbs – imbalances that may remain and impact functional performance once the athlete has returned to sport. Is there any way around this?

Well, very recent research on animals has shown that long-duration stretch training can lead to significant increases in muscle strength, thickness and length(13) – an effect that further recent research found in humans too(14). That has led some scientists to wonder if the inclusion of long-duration static stretching in rehabilitation or general conditioning programs is beneficial to improve the overall outcome in terms of muscle functionality.

Since static stretching does not require active (joint) movement and can be included in seated activities, it can be performed with a high frequency (ie daily) by athletes at any stage of the rehab process or when returned to sport. To date, no study has been conducted to investigate the effects of long-duration static stretch training to treat muscular imbalances. But now a brand new study published by German researchers in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health has investigated the use of static stretching to counteract imbalances in maximal strength and range of motion as a result of previous injury(15).

The research

In this study, 39 athletic participants with significant calf muscle imbalances (of at least 10% or more) in maximal strength and range of motion between the right and left calves were divided into an intervention group and a control group:

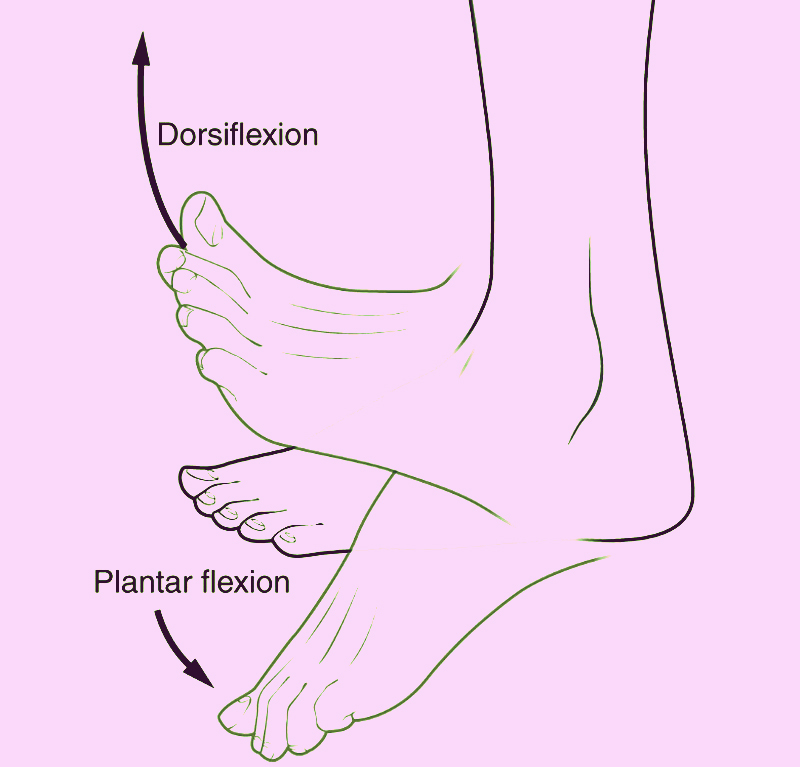

- The intervention group - stretched the calf muscles of their weak leg for one hour per day for six weeks. The stretch intensity over the time course of the intervention was documented by the daily achieved ankle angle, which the subjects read from a goniometer (a device that measures joint angles) in the maximally dorsiflexed (see figure 1) position. The subjects were instructed to reach an individual stretching pain of 8–10 on a visual analog pain scale from 1 to 10, where 0 = no pain and 10 = unbearable pain.

- The control group – simply carried on with their normal daily activities – ie did not undertake any form of long-lasting stretching.

Figure 1: Dorsiflexion (and plantar flexion)

Before and after the intervention, the calf muscle strength levels were measured in both the weak and strong legs of each participant. Strength testing was performed with straight knees and with knees bent at 90 degrees. This was so that both soleus and gastrocnemius calf muscle strength could be assessed. Meanwhile, upper ankle joint ROM was investigated using the ‘knee-to-wall stretch’ test, which is shown in figure 2. The strength and range of movement scores in the weak and strong legs of both groups were then compared to see what effect if any the intervention had produced.

Figure 2: Knee-to-wall range of movement test

The heel remains pressed flat to the floor while the moving wooden wall is moved away from the subject. The subject tries to keep his/her knee against the wooden wall without lifting the heel. The further away the wall is from the toes, the more dorsiflexion is needed at the ankle joint. At the maximum flexion point (just before the heel can no longer be kept flat), the ankle joint angle is read with a goniometer.

What they found

- The results showed significant increases in maximal strength and range of motion following six weeks of static stretching, while no increases were found in the control group.

- In the straight-knee position, there was an increase of 19.9% in maximal strength due to the intervention, while no significant increase could be obtained in the control conditions.

- Likewise, there was an increase of 9.6% in maximal strength in the bent knee position, while no significant increases were obtained in the controls.

- Range of motion using the knee-to-wall test increased by 15.2% with static stretching; once again, there were no improvements in the control group.

- The magnitude of improvements brought about by static stretching helped to largely abolish the discrepancies in strength and range of motion (see figure 3 for example)!

Figure 3: Changes in range of movement discrepancies following static stretching(15)

The stretching group (squares) brought their weak leg strength from 87% of their strong leg up to that of their strong leg (a score of 1.00 indicates perfect symmetry). In fact, the previously weaker leg became even stronger than the strong leg! The control group (triangles) experienced no reduction in strength discrepancy.

Practical implications for athletes

This study is quite groundbreaking as it’s the first to show that a stretching intervention can completely eliminate strength and range of motion deficits in a non-dominant limb. When injury strikes, even a fully rehabilitated knee, ankle, hamstring (insert muscle or joint here) may not recover optimal levels of strength and range of motion. Although athletes can work around a small discrepancy, the evidence suggests that over time, these limb imbalances can become more entrenched and harder to eradicate(16). Moreover, these prolonged deficits potentially increase the risk for injury recurrences due to persistent atrophy and (eccentric) strength deficits in the injured muscles(17).

While strength training is a useful tool for correcting strength imbalances, it’s not always easy performing unilateral strength work; not only are the techniques required a little different, it’s often psychologically hard for athletes to focus on just one half of the body! However, what this study shows is that a period of static stretching interventions could possibly be an effective alternative to common strength training or rehabilitation exercises, especially where access to strength training equipment is limited. Indeed, where increased range of motion is a priority, it could even be a superior option. However, static stretching doesn’t need to be either or; it could also provide a supplement to strength training, helping to provide a double-whammy effect.

One potential drawback of using a static stretching approach is that this study asked athletes to stretch for one hour every day, which is quite time demanding. Could the same benefits be achieved with reduced time input? This is unknown at the moment – however, the stretches in the study were accumulated over the day, which means that totalling 60 minutes per day might not be quite as hard as you might imagine!

References

- Int J Sports Med. 2018 Apr;39(4):243-254

- Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2007 Jun; 2(2):212-6

- Res Sports Med. 2017 Jan-Mar; 25(1):78-90

- Strength Cond. Res. 2014 doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182956461

- J Strength Cond Res. 2010 Sep; 24(9):2274-9

- Front Physiol. 2019; 10():1468

- Front Physiol. 2020; 11():630282

- J. Sports Med. 2013;47:15–26

- 2014;45:1782–1790

- J. Sport. Med. 2015;43:2302–2309

- Muscle Nerve. 1998;21:1006–1012

- Rehabil. Med. 1990;22:33–37

- Sci. Sport. Exerc. :2022. doi: 10.1007/s42978-022-00191-z. in press

- Front Physiol. 2022; 13: 878955

- Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Oct 14;19(20):13254. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192013254

- Ther. 1997;2:11–17

- Sci. Med. Sport. 2018;21:789–793

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.