You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Chest muscle injury: minor or major problem?

While injuries to the pectoral muscles of the chest are not uncommon in athletes, things are more complicated when an injury is focused on the pectoral minor muscle. SPB explains why and discusses how such injuries are diagnosed and treated

Musculoskeletal shoulder pain affecting the chest and/or frontal shoulder can be caused by a variety of conditions. These include contusion (internal swelling) from a direct impact, costochondritis (inflammation of the connective tissue between the breastbone and ribs), a muscle sprain and/or tendon rupture of the main pectoral (chest) muscle, and biomechanical abnormalities affecting the shoulder girdle. However, while rare in athletes, another possible cause is as a result of an ‘isolated pectoral minor’ (PMi) tear.

Sports injury research shows that a PMi tear on its own is most likely to occur in sports where there is a likelihood of direct trauma resulting from a blow to the area. Such sports include American football(1,2) and ice hockey(3). However, not all isolated PMi injuries are caused by trauma. For example, one 2019 study reported the occurrence of a PMi tear in a healthy 24-year old woman as a result of performing a ‘side plank’ (core stability) exercise at the gym– most likely occurring due to a loss of endurance during the exercise(4).

Understanding pectoralis minor function

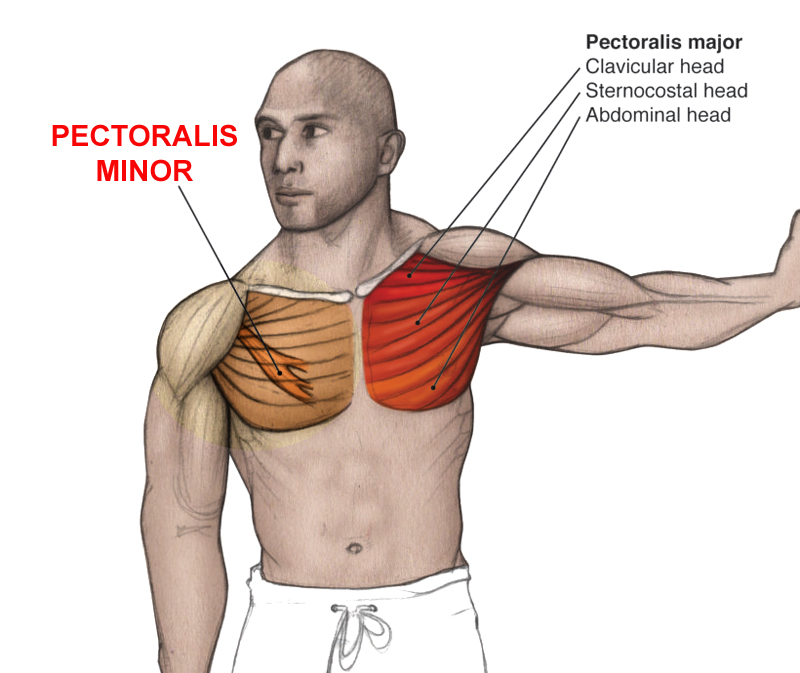

Before we discuss PMi diagnosis and treatment, it’s helpful to understand a little about the anatomy of the PMi muscle. The PMi is a fan-shaped muscle originating from the third, fourth and fifth ribs and inserting onto the coracoid process (a hooked-shaped projection to which many ligaments are attached) of the scapula, more commonly known as the shoulder blade. Figure 1 shows the overall location of PMi, although not where it attaches on the coracoids process). Importantly, the pectoralis minor is located underneath the pectoralis major (the main chest muscle), which is why it is less vulnerable to injury (being protected by its big brother above!).

In terms of its biomechanical function, the PMi muscle pulls the scapula forward, and downward. Therefore, it is principally used in shoulder movements of depression and abduction – ie movements where the shoulders move downwards and inwards to towards the center line of the chest. In addition, the location and function of PMi means that it can aid somewhat in the process of inhalation as an ‘accessory muscle’ (technically, any muscle attached to the upper limb and the rib cage can act as an accessory muscle of inspiration)(5).

Figure 1: Anatomy of pectoralis minor (showing relationship with pec major)

PMi injury mechanisms

Most chest muscle tears involve the pectoralis major, and typically occur from a combination of loaded adduction and internal rotation (the movement of the arms towards the midline of the body) – an injury mechanism often observed in weightlifters or contact sports (eg pushing heavy loads on the bench press)(6). By contrast, the precise mechanism of a PMi sprain or tendon rupture is poorly understood(4). It’s likely that a number of factors may combine to cause injury, which include(2):

· Excessive strain from abnormal loading.

· Cumulative stress and trauma over weeks or months, which exceeds the capability of the muscle tissue to adapt to the loading.

· Chronic PMi shortening and tightness as a result of poor posture or naturally occurring anatomical variations. One posture that encourages PMi shortening is hunched/rounded shoulders - commonly seen when users are looking down at their mobile phones or other devices!

· Direct impact to the front of the shoulder.

· Forced external rotation of the arm (where the upper arm moves outwards or upwards from the midline of the body), especially where the arm starts in slight abduction (towards the center line of the body).

What researchers do agree on however is that rather than the mid portion of the muscle itself, it’s the region where the muscle fibers transition into tendon tissue (the myotendinous junction) that is the most common site of injury in PMi muscle injury(7).

Diagnosis of a PMi injury

Athletes with chest/shoulder pain and who have an isolated PMi injury may struggle to get a correct diagnosis unless they find an experienced physiotherapist. That’s because not only is this injury often mistaken for a pectoralis major injury, in many instances, the two injuries coexist! Indeed, as table 1 shows, there have been a number of research studies in the literature where an isolated PMi injury has been incorrectly diagnosed as a pectoralis major injury. Since a pectoralis major strain (or rupture) has different treatment implications for the athlete, the correct diagnosis of an isolated pectoralis minor tear is therefore important, and will almost certainly require imaging to confirm (table 1)(1,8).

Table 1: PMi/pectoralis major diagnosis confusion

|

Study |

Injury mechanism |

Initial diagnosis |

Imaging results |

|

Mehallo et al. (2004 |

Female football hit on the front of the right shoulder during a tackle. The patient’s arms were by her side at the time of impact |

Grade 1 pectoralis major strain |

MRI indicated swelling and lack of definition of the right PMi muscle. Pectoralis major intact, including the humeral attachment |

|

Kalra et al. (2010) |

Professional ice hockey player received contact with the affected arm in slight abduction, external rotation and extension |

Pectoralis major strain |

MRI showed extensive swelling in the PMi muscle and a complete isolated tendon tear. Pectoralis major was intact |

|

Li et al. (2012) |

High school football player injured when making a tackle and leading with left arm and chest |

No initial diagnosis |

MRI showed significant swelling within the PMi muscle and detachment of the tendon from the coracoids process |

|

Zvijac et al. (2009) |

Two male professional football players (NFL); during practice with blocking exercises. Arm position was in extension with the shoulder in flexion in both cases |

No initial diagnosis |

Cross-sectional MRI imaging showed isolated tear of the PMi muscle |

For the correct diagnosis of an isolated PMi injury, your physio will take a detailed history, with particular attention paid to the mechanism and location of any recent impact. In particular, they will want to know whether that athlete has suffered an injury caused by a direct frontal impact force to the shoulder, forced external rotation of the arm in slight abduction, or with the arm in extension and shoulder in flexion. The symptoms that are particularly important are a ‘pop’ or snapping sensation in the frontal shoulder and/or chest area at the time of injury, and an immediate pain sensation that also began to radiate up to the neck and/or down the chest and arm.

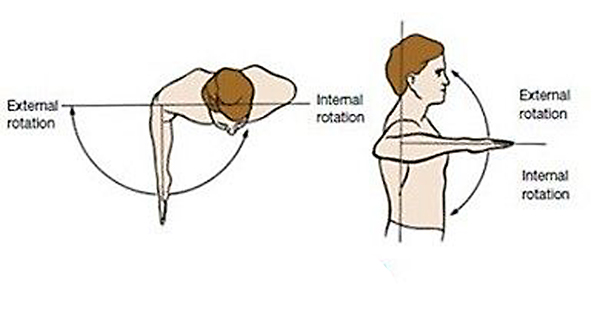

If a PMi injury has occurred, there is typically tenderness upon when applying pressure over the coracoid process, combined with reduced range of motion. Pain and weakness will be common also, particularly experienced during shoulder extension and external rotation (moving arm upwards and/or outwards - see figure 2). There may also be tenderness over the biceps groove (the region at the very top of the biceps where it inserts under the main visible chest muscle) of the affected side. In addition, the main chest (pectoralis major) tendon may be painful when try to move the arm towards the center line of the body while under load (think chest fly movement).

Figure 2: Shoulder extension and external rotation

Will I need imaging?

Due to its deep location and the fact that a PMi injury frequently occurs in conjunction with a pectoralis major injury, MRI imaging is virtually essential for confirming (or refuting) a suspected PMi injury diagnosis. Computerised tomography imaging (CT scanning) may also be useful. Where MRI is used, multiple scans from different orientations using different frequencies will likely be use to build up a really accurate picture of the extent and nature of the injury.

Treatment options

Athletes with complete pectoralis major tears usually undergo surgery to regain optimal function(10). In isolated pectoralis minor tendon tears however, the good news is that non-surgical or ‘conservative’ treatment approach is usually recommended. This approach will entail an initial period of complete rest while the athlete uses icing and anti-inflammatory medication such as NSAIDs (eg ibuprofen). This may also require the athlete to completely immobilize the affected side with the use of a sling, which allows the healing process to begin. Following this initial period of rest, the athlete can begin some gentle activity, but modified to avoid offending movements involving the chest and shoulder. This period will typically last between two and four weeks.

After 2-4 weeks of activity restriction, the athlete can begin a more active phase of rehab, which typically lasts up to 12 weeks. This is recommended to include neuromuscular and strength training, along with scapular stabilizing exercises - see this video for what this entails: www.youtube.com/watch?v=VcR3RmdkVUI.

During this period, the loading and intensity training is gradually increased (see an example below in box 1) of the kind of progression that can be used. It is important to understand that with PMi tendon tears, while shoulder strength may decrease slightly compared to pre-injury baseline, the overall functional outcome is unlikely to be compromised, and that athletes can expect to return to their normal level of sport participation once full rehabilitation has taken place.

Box 1: Conservative treatment for PMi: example of rehab protocol

(Protocol used in an ice-hockey player)

- Week 0 - Sling and physical therapy.

- Week 2 – Passive external rotation, passive abduction, and scapular retraction avoided.

- Week 3—Active abduction can be initiated. Careful return to skating.Week 4 – Cautious return to play (without pain/weakness) but with upper body strengthening initiated including scapular retraction/protraction as well as shoulder depression exercises.

- Week 8 - Pain-free push-ups achieved.

- Weeks 8+ - Patient played the remainder of the season without re-injury or shoulder complaints.

In summary

Isolated PMi injuries are comparatively rare and difficult to diagnose. A correct diagnosis requires careful history taking to determine the mechanism of injury and a detailed physical examination. MRI imaging will typically show swelling at the tendon insertion site of the pectoralis minor muscle onto the coracoid process, along with an intact pectoralis major muscle. Conservative treatment approaches are usually recommended and most athletes can expect a full recovery with no long-term detriment to performance.

References

1. American Journal of Orthopedics 2009; vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 145–147

2. Orthopedics 2012, vol. 35, no. 8, pp. e1272–e1275

3. Skeletal Radiology 2010; vol. 39, no. 12,pp. 1251–1253

4. Case Rep Orthop. 2019 Aug 29;2019:3605187

5. Moore KL ,Dalley AF . Clinically oriented anatomy. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005

6. Arthroscopy Techniques 2012; vol. 1, no. 1, pp. e119–e125

7. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, vol. 19, pp. 419–445, 1991

8. Clin J Sport Med 2004;14(4):245–6

9. Radiol Case Rep. 2018 Oct; 13(5): 1053–1057

10. Am J Sports Med 2010;38(8):1693–705

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.