You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Knee injury: when pain serves to deceive

Pes anserinus injuries can cause debilitating inner knee pain in athletes, mimicking knee joint damage, which sometimes leads to unnecessary surgery. Why do they occur, and how can they be correctly diagnosed, treated and prevented? SPB looks at what the research says

Injuries affecting the knee are extremely common in athletes, not least because of the wide variety of injury mechanisms and the loads transmitted through the knee joint during sport. When medial knee pain (pain affecting the inner side of the knee joint) occurs, there are a number of possible causes, including an injury to the ligaments, cartilage/meniscus of the inner knee, or even a tibial stress fracture of the lower leg. However, in athletes whose sports include vigorous and repetitive hamstring use (in short, anyone who has to run a lot or fast!) there is another possibility – a pes anserinus injury. Although comparatively rare in athletes, it is important that a pes anserinus injury is diagnosed correctly – not least because missing such a diagnosis could result in unnecessary surgery.

What is the pes anserinus?

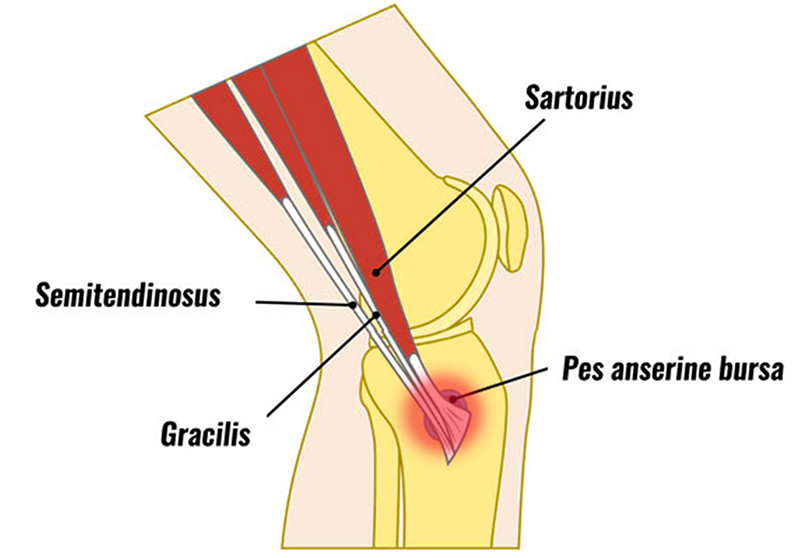

The pes anserinus (which we will refer to simply as ‘PA’ from this point) - also known as pes anserine or the ‘goose’s foot’ – refers to a combined tendon structure of the insertion of three hamstring muscles (the sartorius, gracilis and semitendinosus) along the upper, inside portion of the tibia bone of the lower leg (see figure 1). The three combined tendons all attach together to the tibia on the inner part of the lower knee. Visually, these ‘conjoined’ tendons form a structure reminiscent of a goose’s webbed foot and are named by anatomists from the Latin pes for foot and anserinus for goose. Underneath these three conjoined tendons lies the ‘pes anserine bursa’. This is a fluid-filled sac dedicated to providing smooth movement of the three conjoined hamstring tendons and the medial collateral ligament, which runs across the inner knee.

Figure 1: Structure of the pes anserinus

Although it doesn’t affect the injury itself, it’s worth pointing out that the description of the structure of the PA shown is figure 1 is rather oversimplified in that there is a lot of variation from person to person. Research shows that additional bands of tissue may be present with the tendons and that the insertion shape can vary greatly – for example being short, band-shaped or fan-shaped(1). Although this might sound strange, it’s actually quite commonplace. The human anatomy is rarely exactly as described in the textbooks, and many of the muscle and tendon structures display a large degree of variation from person to person!

Causes of PA injury

Pain as a result of a PA injury can arise as a result of inflammation of the three conjoined PA tendons, inflammation of the PA bursa underneath or both. Clinically, it is difficult to diagnose what is causing it but for physios and athletes, this is of little significance because the treatment is the same for both conditions. Having said that, the evidence suggests that a PA bursitis (inflammation of the sac) occurs more frequently and responds more quickly to treatment than tendon inflammation(2).

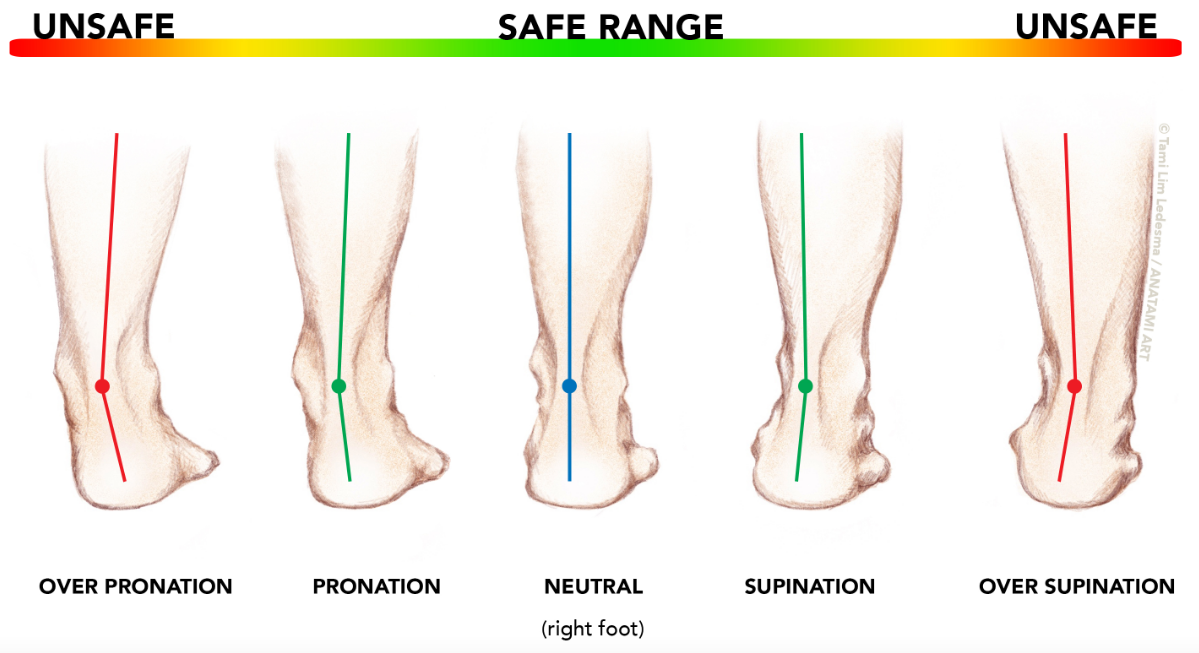

The underlying factors increasing the risk of a PA injury are often multifactorial, but in athletes, typically involve high hamstring loadings combined with sub-optimal biomechanics. Movements that can precipitate a PA injury are those involving excessive pronation in an athlete’s running gait (where the ankles roll inwards too much placing stress on the medial side of the knee – see figure 2), rotation stresses to the knee, as well as a by a direct blow or impact(3).

Figure 2: Pronation and ankle movement

Given the above, it is perhaps unsurprising that PA tendonitis and bursitis is more often observed in long-distance runners than many other athletes(4). Indeed, any weakness at the knee joint causing mechanical stress or loading to the inner knee can be a risk for PA injury(5). This is not surprising as one of the functions of the sartorius/gracilis/semitendinosus tendon complex is to aid knee stability by helping the ligaments of the inner knee resist such forces. It is also believed by some researchers that PA injury and pain could be more common in older athletes where there might also be some knee osteoarthritis present(6). However, other researchers disagree, arguing that in older persons with a degree of pre-existing osteoarthritis, some pathology affecting the PA is to be expected – however, this is distinct from a PA injury caused by repetitive overload involving the hamstring muscles.

Diagnosing a PA injury

Athletes who develop a pes anserine bursitis (inflammation of the sac under the tendon insertion) typically experience symptoms of tenderness and swelling along the inside of the lower portion of the knee joint (inside top of tibia). However, symptoms may also include vague ‘inside of the knee’ pain, which may is very similar to the pain of a torn medial meniscus or ligament(7). Indeed, some research suggests that a significant proportion of patients may not experience the swelling symptoms described above, but instead present with pain solely on the inner side of the knee joint, raising a (false) suspicion of a meniscal tear(8). Other symptoms that can indicate a PA injury are typically as follows:

· -Pain experienced approximately 2-3 inches below the inner side of the front of the knee joint (which may also extend to the front of the knee and down the lower leg).

· -A gradual onset of pain over a prolonged period of time.

· -Exacerbation of pain occurring on ascending or descending stairs or steep gradients, or sitting down/rising up from chairs.

· -A lack of pain when walking on level surfaces.

· -Pain experienced when contracting the hamstrings against resistance.

· -Pain upon stretching the hamstring muscles.

· -In more severe cases, pain at night, waking the patient when he/she bends the knees resulting in sleep disturbance.

What your physio will look for

A successful diagnosis of PA requires a thorough physical examination, along with a detailed history of the symptoms and characteristics of the pain presentation (see above). In particular, the physio will want to identify the exact site of pain by both feeling and pressing (palpation) the area. He or she will also want to identify the pain-producing movement(s) during a physical examination in order to be really sure of the diagnosis(9).

Because the PA is close to the skin surface, ultrasound imaging has been shown to be an effective method to help diagnose PA bursitis, cysts, tendonitis(10). However, the gold standard for PA imaging is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In particular, the appearance of fluid beneath the pes anserineus tendon near the joint line at the inside of the tibia (a real tell-tale sign of PA injury) can often be seen on an MRI, which explains why it is considered to be a superior method compared to ultrasound(7). Regardless of imaging used however, the athlete’s history, examination and pain presentation characteristics remain the cornerstone of any diagnosis. Imaging is perhaps more important for exclusion of other conditions that may present with similar symptoms. These include(11):

· -A tibial stress fracture

· -Osteoarthritis

· -Popliteal cysts (fluid-filled lumps at the back of the knee, which can cause pain)

· -Infection of the PA bursa

· -Malignant tumor (rare)

Something else that imaging can identify is a condition known as ‘snapping PA syndrome’, which some athletes experience as a sensation of inner knee snapping when the joint is moved through a range of motion. This snapping sensation results from rubbing of the PA tendons (usually gracilis or semitendinosus) across the lower portion of the femur (thigh bone) and the tibia bone during active movement of the knee from flexion to extension(12,13). Snapping PA syndrome has been reported in athletes as a result of overuse and trauma. However, while static imaging forms part of a diagnosis, dynamic imaging (ie during the snapping movement) is also essential to confirm a diagnosis(14).

How is a PA injury treated?

Treating a PA injury in athletes generally requires a three-pronged approach:

1. Identifying the activity or activities leading to the injury, and immediately removing it/them from the athlete’s training routine.

2. Introducing strategies to reduce inflammation in the PA complex – for example the application of regular ice packs combined with anti-inflammatory medication such as Ibuprofen(15).

3. Assessing the athlete’s movement biomechanics relating to their sport – in order to identify and correct the underlying causes of the injury – and rehab training to reduce the risk of re-injury once normal activity is resumed.

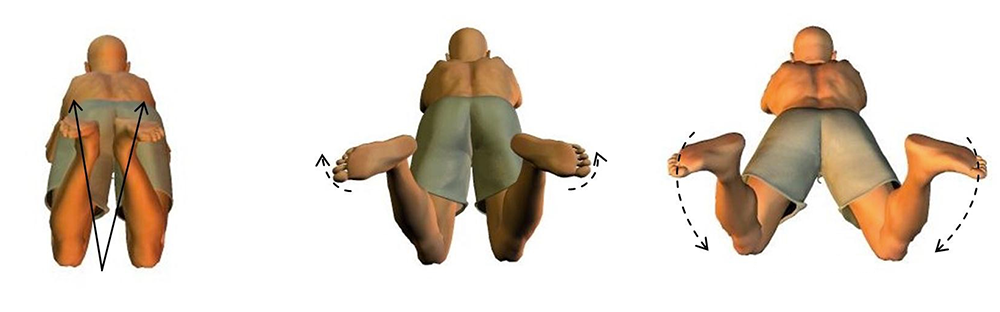

As we said earlier, in many athletes, the most-likely offending activity will involve running. Other activities that involve significant and repetitive hamstring (and therefore PA) loading include rowing, speed skating and breaststroke swimming. Swimmers who use mainly breaststroke are particularly vulnerable because this movement requires hamstring contraction combined with rotation at the knee (see figure 3). In addition to removing offending activities, athletes who are side sleepers may also benefit from using a pillow between the knees at night, which helps alleviate direct pressure on the PA tendons and bursa.

Figure 3: Breaststroke and hamstring/PA loading

Conventional treatment strategies

Treatment strategies to help reduce initial pain and swelling (if present) include regular icing (15-20 minutes every two to three hours) and the use of over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medication such as Ibuprofen. In more severe cases, your physio may recommend the use of stronger NSAIDs such as Naproxen. Another early-intervention treatment strategy that may be useful is ‘kinesiotaping’. This process involves applying flexible tape around the site of an injury in order tension and lift the tissue, thus creating ‘space’ under the skin and relieving pressure, which aids in the recovery process. Kinesiotaping has been shown to be surprisingly effective; in one study on 56 patients with a PA injury, kinesiotaping was actually more effective in relieving pain and swelling than the commonly prescribed anti-inflammatory Naproxen(16)! This may be important consideration in athletes who are sensitive to NSAID medication – eg experience heartburn and/or gastric discomfort.

Returning to sport

In most cases, removing the offending activity, regular icing and NSAID medication or taping will allow the discomfort of a PA injury and any swelling to subside within 2-3 weeks, after which appropriate stretching and strengthening exercises can be carried out as the first stage of rehab. The length of this rehab period will vary according to the individual, but can typically be expected to last from 3-8 weeks(17). At this point, your physio will likely want to carry out a biomechanical assessment of your lower limbs and analysis your training regime.

In particular, he/she will want to ensure any biomechanical factors leading to excess valgus (inner knee loading) forces are reduced to a minimum before you begin active rehab. In runners, this means careful observation of running gait and shoe characteristics. Where excessive pronation is present, shoes emphasizing motion control are recommended – with the addition of orthotic inserts where necessary. The use of a knee brace or support with additional protection at the sides may also help - although of course, this option does not remove the offending motion, but instead merely attempts to control it.

Stretching and strengthening

In the early stages of PA injury rehab, stretching of three muscles and tendons that conjoin at the PA (sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus) is strongly recommended since passive and active stretching can promote a significant reduction in the tension experienced by the PA bursa, which lies underneath. This can be achieved with a variety of hamstring and adductor (inner thigh muscle) stretches such as the ‘butterfly stretch’, also known as the seated adductor stretch. Calf and quadriceps stretching is also recommended.

Figure 4: Resisted perturbation in half-kneeling position

Injection treatments

In the large majority of cases, the conservative treatment options outlined above are able to fully resolve PA injuries. In more severe and/or chronic cases of PA injury however, alternative treatment methods may have to be considered. One possible route is the use of injection therapy, which can produce short-term pain relief and longer-term improvements (over a 3-6 month period) in patients suffering from chronic PA syndrome(18,19). In rare cases when the PA injury still doesn’t settle and resolve, surgery may be required. This is normally carried out via keyhole surgery under a local anaesthetic, with the goal of removing scar/inflamed tissue and/or bone debridement. Debridement creates more ‘room’ around the PA tendons and bursa, thereby relieving pressure, and research shows that as well as being a straightforward procedure, it has few complications, a low relapse rate, with good function restored after surgery(20).

References

1. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019 Sep;27(9):2984-2993

2. Skeletal Radiology 2005; 34(7):395-398

3. Donoghue DH. Injuries of the knee. In: O Donoghue DH, ed. Treatment of injuries to athletes, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1987: 470–471

4. Orthop Clin North Am 1995; 26:547–549

5. J Clin Rheumatol. 2007 Apr;13(2):63-5

6. Mod Rheumatol. 2015 Jan;25(1):128-33

7. Radiology 1995; 194:525–527

8. Skeletal Radiology 2005; 34(7):395-398

9. JAMA 1937;109:1362-1366

10. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Apr; 97(15): e0352

11. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2010;50(3):313-327

12. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;199:142‑50

13. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008;90:334‑5

14. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2017; 7: 39

15. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2010 May-Jun;50(3):313-27

16. Phys Sportsmed. 2016 Sep;44(3):252-6

17 The Lower Limb Tendinopathies: Etiology, Biology and Treatment edited by Giannicola Bisciotti, Piero Volpi doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33234-5

18. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2014 May-Jun;16(3):307-18

19. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Oct;96(43):e8330

20. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2009 Sep;23(9):1045-8

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.