You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

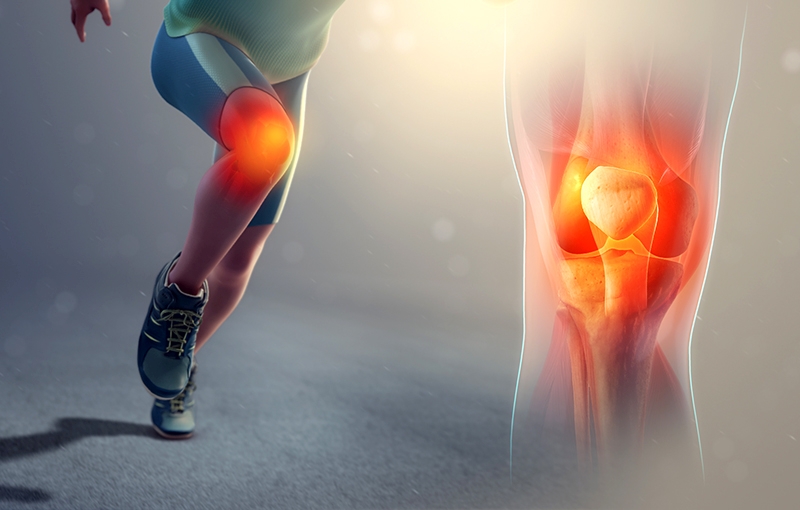

Lateral knee pain and iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS)

Looking at the causes of lateral knee pain and ITBS

There are numerous complaints affecting the knee, but in this article I have focused on lateral knee pain, having treated a number of people with this problem in recent weeks. In cases of chronic lateral knee pain, iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) should be considered as a possible cause. An athlete with this complaint will experience sharp stinging pain on the outside of the knee, which may be sufficiently intense to cause a limp.

In weight training, lateral knee pain can be induced by squats, lunges, hamstring curls, extensions and any motion that involves repetitive flexion and extension of the knees. In runners it may occur as a result of running up and downhill and on banked surfaces. Whatever the trigger for the problem, correct diagnosis and treatment are vital to allowing a return to pain-free activity.

The iliotibial band (ITB) is a long ligament-like structure running along the outside of the thigh, formed within the tendons of the gluteus maximus and tensor fascia latae muscles. It connects the ilium, the large flared portion of the pelvic bone, with the upper part of the tibia (shinbone). When the knee is flexed more than 30 degrees, the iliotibial band (ITB) lies on or behind the lateral femoral condyle, the bony prominence that makes up the upper and outer portion of the knee joint. When the knee is extended, the iliotibial band (ITB) lies in front of the lateral femoral condyle. Repetitive flexion and extension move the ITB back and forth over this bony structure.

Poor training habits lead to knee pain

Normally this mechanism functions correctly and the knee flexes and extends without pain. When it doesn't, you get ITBS. A number of factors can trigger ITBS, but poor training habits are the key culprits. Any sudden increase in training intensity - whether that increase comes from extra weight, an increase in reps, greater distance or training on uneven ground - can lead to lateral knee pain. The problem can also be caused or exacerbated by structural abnormalities within the body, including pelvic torsion or obliquity, sacroiliac joint abnormality, and foot pronation (foot turning inwards) with excessive internal tibial rotation (shinbone turning inwards).

In most cases, evaluation of the problem is straightforward. The athlete will complain of knee pain brought on by repetitive flexion and extension and may report a limp following exertion. Swelling is not usually evident and there is no history of acute trauma - an instant injury caused by falling over or hitting the knee on a hard surface. Full weight bearing on the affected leg with the knee in 30-40° flexion will reproduce the pain, as the ITB comes in contact with the lateral femoral condyle. The athlete will be asked to lie on his back with the knee bent to 90°. The therapist then applies finger pressure over the ITB insertion at the lateral knee and extends the leg, causing pain at about 30° flexion. The tightness of the ITB can also be assessed by means of the 'Obers test'. The athlete lies on the unaffected side, with the hip and knee flexed to flatten out the lumbar spine, while the therapist grasps the lower calf of the affected leg and flexes it to 90°. After bringing the thigh in line with the athlete's torso to maximally lengthen the ITB, the therapist brings the affected leg towards the table. If tightness is a factor, the leg will remain elevated in proportion to the amount of shortening of the ITB.

Thankfully, treatment is also relatively straightforward. Ice packs applied for 15 minutes every two-and-a-half hours - with a towel between the ice and the skin - reduce acute pain and intercellular fluid accumulation, while non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication will assist pain control. Electrical muscle stimulation (EMS) is a very good form of physical therapy as it helps trigger points in the gluteus maximus/medius and tensor fascia lata muscles. Once the acute pain has been reduced, ITB stretching can begin. The athlete lies on a table on the unaffected side with that hip and knee flexed. The affected leg is brought behind the torso, with the injured knee straight and the leg hanging off the table, where gravity will stretch the ITB. Another stretch is performed in a standing position, with both knees straight: the affected leg is brought behind the body and as close to the unaffected side as possible, while the athlete bends his torso as far as possible towards the unaffected side.

Athletes are normally advised to continue exercising, as long as they avoid activities which aggravate the pain - and that normally includes running. Lower body weight training can be performed - with certain modifications. But the aim of training during this acute injury phase is to minimise losses rather than to maintain peak strength levels. Never train through an injury in the hope that it will go away. It may do in some cases, but it will return to plague you in future - and with more serious consequences!

Squats can be performed in a range of motion that will avoid pain - ie from standing to a bent knee position of 30°. (ITBS pain usually occurs at 35° flexion.) Back squats, assisted by a partner, can be performed on a Smith machine, moving from a bent-knee position of 90° to a semi-erect position of 45-30° of knee flexion, which avoids the painful portion of the range of motion.

Leg presses can be done from a bent-leg position to a semi-extended position between 30 and 45° of knee flexion, while quad extensions can be done from 90° of knee flexion to an extended position of 45-30°. Hamstring exercises can be done from a straight-legged position to a bent-knee position of 30-45°. Calf exercises need no adjustment since they are done with straight legs for the gastrocnemius, or seated with knees bent at 90° for the soleus. Swimming is useful for maintaining cardiovascular fitness, as long as you concentrate on the front crawl rather than breaststroke.

After a period of 2-4 weeks, when acute pain has subsided and lateral knee pain can no longer be reproduced in the tests described above, the athlete can return to using a more complete range of motion during lower body weight training. The body takes time to recover from an injury and there are no short cuts in this area.

To avoid lateral knee pain from ITBS, take a hard look at your current training routine and check that you are warming up and cooling down correctly, as well as stretching. (See 'Almost everything you need to know about stretching', page 8). These exercises need to be carried out in a logical order, not haphazardly. The body is an amazing piece of evolutionary engineering but, while it is flexible, it will not tolerate abuse indefinitely. Always listen to your body and rest when appropriate, or shift the focus of your training to another part of your body. Finally, bear in mind that this information is not intended to replace the advice or attention of health care professionals. Always consult your doctor for diagnosis and treatment of injuries.

Carl Fisher

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.