You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Shin hernias in athletes: the connective tissue connection

Although uncommon, muscle herniation of the shin muscle in athletes may be far more prevalent than previously thought. SPB explores the causes, diagnosis and treatment options for this injury

A muscle herniation injury (technically referred to as a ‘myofascial defect’), is when there is a protrusion of a muscle through the surrounding connective tissue (fascia). In effect, muscle tissue that should remain sheathed and protected by the fascia poke through to the surface. The most common location of muscle hernias in active muscles is in the leg. However, because this type of injury is tricky to diagnose and rarely brought to the attention of medical professionals, there is actually relatively little data in the scientific literature about it(1-3). In fact, the majority of early research on leg hernias (and much of our current knowledge today) stems from the efforts of military surgeons during the 1940s, detailing lower-extremity muscle hernias in military recruits undertaking strenuous exercise(4-7).

How common are leg hernias?

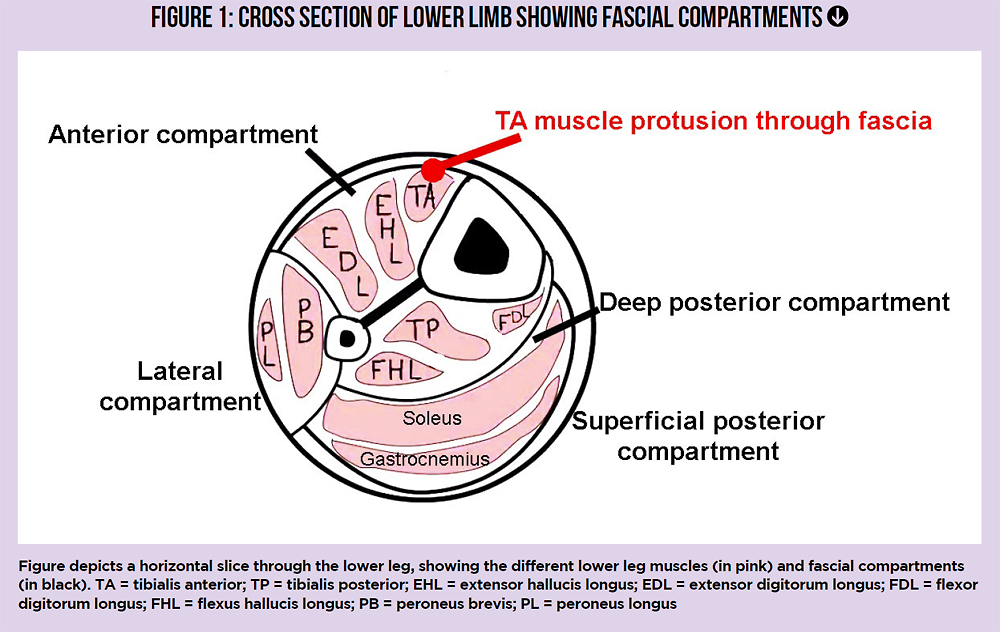

Although it seems remarkable, the true incidence of leg hernias is not known. This is because many lower limb hernias are asymptomatic, and therefore remain undiagnosed because they are never brought to the attention of a physician or physiotherapist(8). Of those lower-limb hernias that are diagnosed however, research has established that a tibialis anterior (TA – the muscle spanning the length of the shin bone) hernia is by far the most commonly involved muscle(9-12). This is almost certainly because with little body fat under the skin of the shin and a solid bone behind, the fascia of tibialis anterior is particularly vulnerable to trauma – for example from a blow to the shin(13). Having said that, it’s important to appreciate that although much rarer, other lower-leg muscle hernias can occur. These include hernias of peroneus brevis(14), extensor digitorum longus(15), gastrocnemius(16) and flexor digitorum longus (see figure 1)(6).

What causes a TA hernia?

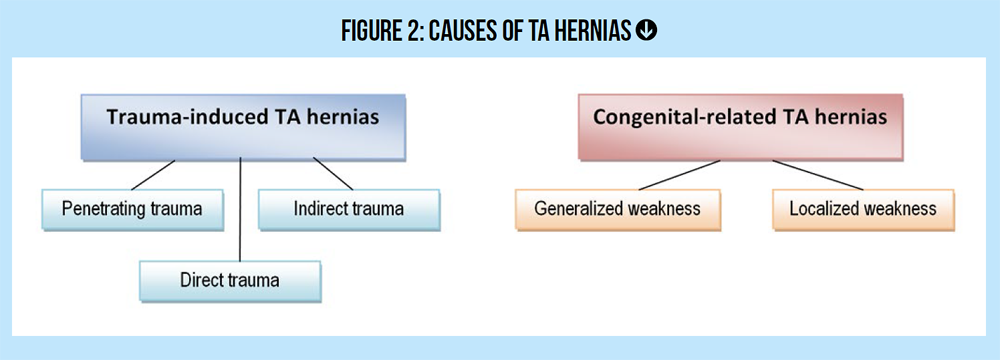

Being a more uncommon condition, much of what is known about TA hernias arises from observational findings. However, what is known is that TA hernias are associated with trauma, either direct or indirect, and/or an innate weaknesses of the fascial tissue surrounding the TA (see figure 2). This innate weakness may involve the fasical tissue as a whole, or be localized at the sites where blood vessels and nerves pass through the fascia(17).

Examples of the kind of trauma that can cause a TA hernia include(18):

· A penetrating injury.

· A direct trauma causing a fracture of the tibial bone, leading to a fascial tear.

· An indirect trauma – most commonly a large force applied to the contracted TA muscle, which causes a sudden fascial rupture.

What about athletes who suffer a TA hernia without any history of trauma? In these cases, there is almost certainly a degree of innate weakness in the TA fascial tissue. And it turns out that innate fascial weakness is much more common than appreciated; for example, one study found that fascial weakness were present in 15% to 50% of patients undergoing surgery for a unrelated condition known as ‘chronic exertional compartment syndrome’ (CECS) – even though their pre-operation examinations were entirely normal(19).

Another factor that increases the risk of TA herniation is athletes is exercise loading. When exercise volumes are high – particularly cardiovascular exercise such as running, the TA muscle grows in size, increasing the pressure in the fascial compartment. If that fascial tissue does not readily yield to accommodate the increase in muscle volume, the risk of a fascial defect leading to a TA hernia increases greatly(20). These factors help to explain why those engaged in activities with high lower limb loadings such as soldiers, athletes, mountain climbers, skiers etc are at much greater risk of developing a TA hernia than the population at large(21).

Related Files

How are TA hernias diagnosed?

When an athlete suffers from a TA hernia, he/she will typically present with a range of symptoms, including:

· A localized swelling or nodule(s) over a portion of the frontal shin, which is soft in nature and may be mildly tender.

· A dull pain that is largely localized to the site of the swelling, but which increases upon weight bearing and activity.

· Feeling if cramping, discomfort and weakness in the affected lower leg.

· Possible numbness in the side portion of the lower leg and foot of the affected side.

· A decrease in swelling when the lying flat on the back (supine) or when the lower leg muscles are completely relaxed.

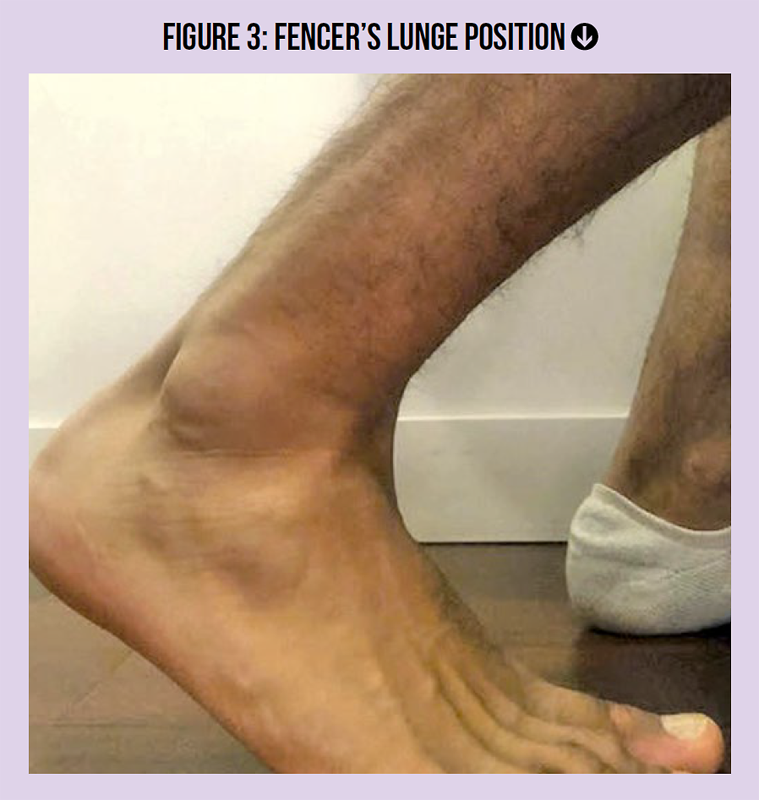

· A marked increase in localized pain and swelling size when the lower leg on the affected side is placed in the ‘fencer’s lunge’ position (see figure 3).

· If the observed swelling/nodule can be felt, and is reduced with muscle inactivation or lying on the back, clinicians can have a fairly high degree of confidence that a TA hernia is present.

Choosing a physio

Athletes who are suffering from an injury with the above symptoms are advised to seek out a physio with a good background in lower-limb trauma injuries if possible. That’s because it’s important that clinicians are able to differentially diagnose a TA hernia injury from other conditions such as lipomas, hematomas and fibromas, which may present similarly. A correct diagnosis of TA herniation as soon as possible means that not only will athletes be able to start the process of rehab sooner, it will also prevent them from undergoing unnecessary skin biopsies, with all the potential worry and psychological side effects this procedure can generate in a concerned patient.

A diagnosis should also take into account the athlete’s history. Where a TA hernia occurs as a result of trauma, he or she may report having experienced particularly intense pain at the time of injury, and there may be signs of the original trauma (scarring/bruising) still visible. In congenital cases (where the fascia is innately weak), no signs of trauma will be evident.

Due to its rare occurrence TA hernias are frequently misdiagnosed as more serious pathologies. But if there is a lack of clinical and orthopedic red flags, clinicians should be guided away from unnecessary procedures such as skin biopsies, especially if the symptoms present following a trauma(22) Having said this, diagnostic imaging is still advised to confirm the diagnosis, especially since there are a variety of differential diagnoses that require exclusion. These include epidermoid cysts, lipomas, tumors, hematomas, angiomas, arteriovenous aneurysms, ruptured muscle and central neuropathy(18).

Is imaging required to diagnose a TA hernia?

If there remains any doubt about diagnosing a TA hernia, the gold standard for imaging in the first instance is not MRI but ultrasound, due to its relative ease, availability and low cost(23). Where possible, this ultrasound should be of the 3-dimensional dynamic ultrasound scanning type because it provides a better 3-D visualization of the fascial planes and any muscular protrusion(24). However, if conservative treatments for a TA hernia (see next paragraph) fail and surgery is needed, or where ultrasound imaging is inconclusive, an MRI can provide a lot of useful extra information. This is particularly the case where surgery is required (see later) because MRI can accurate image the neighboring neuromusculoskeletal tissues, allowing a surgeon to see that kind of surgical intervention is required.

Treating a TA hernia

There’s no clear consensus on the best way to treat a TA hernia using conservative (non-surgical) methods and that’s because there’s not an abundance of data in the medical literature. For small TA hernias that cause no symptoms (rare, since most TA hernias produce a number of troublesome symptoms), the goal is to ensure that athletes take sensible steps not to worsen the condition(25).

This involves protecting the frontal shin area from possible blows (eg wearing shin guards during contact sports). Protecting the shin from types of pressure is also important - eg ensuring minimal contact between the shin and hard surfaces if you work in a manual occupation, especially one that involves crawling around a lot on the floor, such as a carpet fitter or plumber. In a similar manner, athletes should be discouraged from increasing exercise loading of the lower leg, which encourages hypertrophy (growth) of the TA muscle, worsening the condition. For example, an athlete with an asymptomatic TA hernia should most definitely NOT take up running, or increase running mileage if already doing so!

What about a symptomatic TA hernia?

Even though there’s no consensus on treating a TA hernia without surgery, fairly recent research has pointed to a way forward. In a 2020 paper, scientists cited evidence that a proactive approach, combining isometric, eccentric and plyometrics-type exercises, can yield useful results(27). In this research, a 28-year-old male soccer player presenting with a trauma-induced TA herniation injury to his right shin undertook the following protocol:

· Stage 1 (approx. two weeks) – Rest (ie non-weight bearing), the use of full-length compression socks, and isometric contraction exercises for the tibialis anterior muscle (in a supine position to minimize any potential intracompartmental pressure from weight bearing). The use of isometric contraction is to help activate key motor units that can decrease pain during exercise(28).

· Stage 2 (approx two weeks) – Exercise loading progressed to concentric contraction of TA muscle in supine and in weight bearing (standing) positions.

· Stage 3 - Eccentric exercises for the TA muscle to generate force over a greater muscle length and to stimulate maximal tissue adaptation to elastic force (ie to increase the elasticity of the TA muscle). This type of exercise seems to be effective because the elastic energy stored during the lengthening phase of the eccentric muscle contraction can be used during the shortening phase of muscular contraction to amplify force and power production during exercise(29). This in turn means less effort is required to contract the TAS muscle, thus reducing loading on the adjacent fascial tissues.

· Stage 4 - In the last stage of this rehab protocol, sports-specific plyometrics exercises are introduced to generate sports-specific multidirectional force and stability through neural adaptation (training the motor nerves that supply the muscles). Custom orthotics may also be recommended in order to reduce the loading on the TA muscle, reducing its size, thereby reducing the intercompartmental pressure and strain on the facial tissue.

Surgical treatment

When TA herniation occurs as a result of trauma, a graded, stepwise, conservative treatment approach may produce good results within a period of around eight weeks or so, depending on the injury. However, where the cause is because of a fundamental and inherent weakness in the fascial tissue, or where there is a chronic history of TA herniation in an athlete, a surgical repair may need to be undertaken. Traditionally, the most commonly used surgical technique has been to simply close the gap in the fascia. However, this often results in a high re-herniation rate because it also increases intracompartmental pressure, increasing the risk(30). A more recent (and more successful) surgical approach is to use a procedure known as ‘longitudinal decompressive fasciotomy’, which results in less intracompartmental pressure and lower rate of re-herniation. An alternative surgical option is to repair the fascia using synthetic patches.

References

1. Br J Plast Surg. 1976;29:291–4

2. BMJ. 1943;1:602–3

3. Am J Surg. 1945;67:87–97

4. Br J Surg. 1949;36:405–8

5. Bull US Army Med Dept. 1944;77:111–2

6. US Naval Med Bull. 1943;41:404–9

7. Mil Surg. 1943;93:308–10

8. J Am Med Assoc. 1951 Feb 24; 145(8):548-9

9. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28:465–9

10. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989:249–53

11. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:641–2 JCR. 2012;2:42–4

12. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:123–4

13. Br J Dermatol. 1976;95:329–30

14. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977 Apr; 59(3):404-5

15. PM R. 2009 Dec; 1(12):1109-11

16. Orthopedics. 2010 Nov; 33(11):785

17. Can J Plast Surg. 2013 Winter; 21(4): 243–247

18. Orthop Rev. 1993 Nov; 22(11):1246-8

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.