Calf strain: what all athletes should know about diagnosis, treatment and recovery

You don’t have to play tennis to be struck with tennis leg. Alicia Filley describes how this all too common injury can trouble any endurance athlete

Lower leg or calf strain became known as ‘tennis leg’ because calf injuries were first described in 1883 in lawn tennis athletes. Statistics on the incidence of leg strain in sportsmen and women more generally are sparse. However, researchers estimate that 12% of professional footballers experience calf strainAnn Sports Med Res 2015. 2(5):1032. An injury more common in middle age athletes, calf strain occurs 70% more often in males than femalesCurr Sports Med Rep. 2016 Sept-Oct;15(5):320-4.

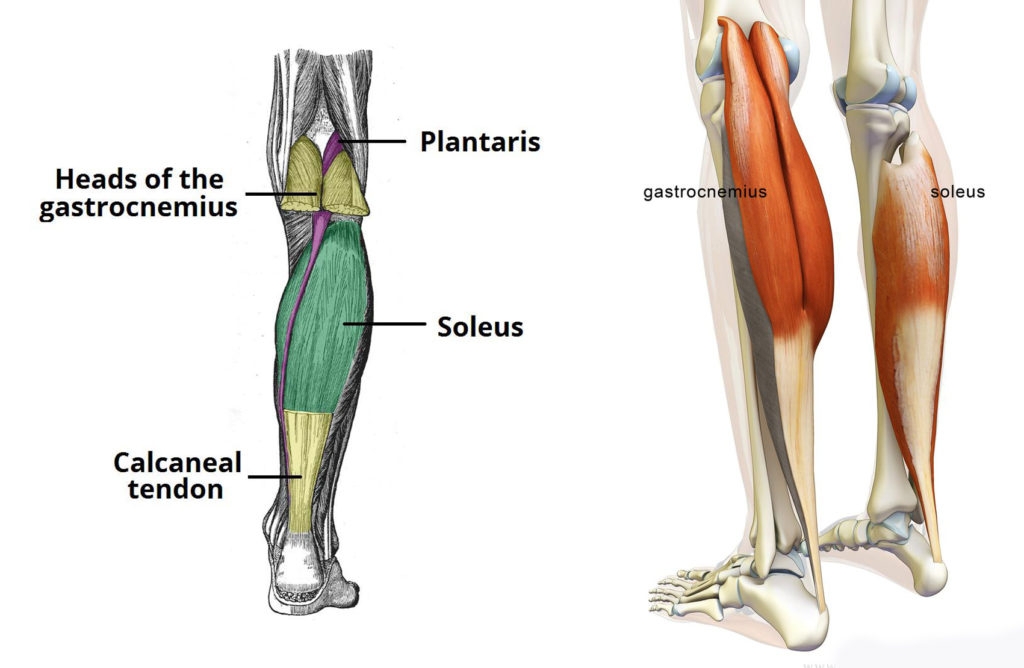

Calf strain affects the more superficial muscles of the calf. These muscles (known collectively as the triceps surae) are the gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantaris muscles (see figure 1). The plantaris muscle is an accessory muscle, which has little functional use. In fact, studies have shown that up to 20% of the population doesn’t have oneBMJ Case Reports 2013 Jan 22! When it is present, this small muscle passes across both the knee and ankle joints, and weakly helps with knee and ankle flexion (bending).

The gastrocnemius likewise crosses the knee and ankle joints. It originates as two distinct heads, one on each side of the femur, where it assists the hamstrings with knee flexion (bending). It inserts onto the heel bone (calcaneus) through the Achilles’ tendon, where it acts to plantar flex (point) the foot downward. The soleus, the third muscle in the triceps surae, also acts as a plantar flexor. It originates along the back of the leg bones (tibia and fibula), lies under the gastrocnemius, and shares the Achilles’ tendon with the gastrocnemius as it inserts at the heel.

FIGURE 1: SUPERFICIAL MUSCLES OF THE CALF

Mechanism of injury

Athletes who suffer from calf strain usually hear or feel a ‘pop’ and experience an intense, searing pain in the back of the leg. The sudden pain of a calf strain was once thought to be a torn plantaris muscle. However, the plantaris is actually the least commonly affected muscle. Indeed, one study found that injury to the plantaris occurred in just 1.4% of the cases evaluatedCurr Sports Med Rep. 2016 Sept-Oct;15(5):320-4.

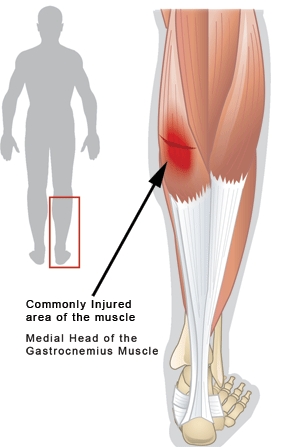

Sports doctors now know that the majority (up to 65%) of all cases of calf strain occur in the medial head of the gastrocnemius – the band of muscle on the inner side of the calf (see figure 2)Curr Sports Med Rep. 2016 Sept-Oct;15(5):320-4. However, the strain may also extend to the outer side in around one third of cases. Consisting mostly of ‘type II fast twitch fibres’ (see page 5 of the African running article in this issue), the gastrocnemius acts powerfully during sprinting and jumping, making it vulnerable when performing running speed drills (such as interval training), hill training, or simply quickly changing direction. Over half of calf strains involve the soleus as wellCurr Sports Med Rep. 2016 Sept-Oct;15(5):320-4. The soleus is made primarily of type-I slow twitch fibres. Injuries to the soleus tend to occur during long distance runs, and may be the result of overtraining. Typically, runners find that it’s not uncommon for a soleus strain to become painful up to 24 hours after a long training run or raceCurr Sports Med Rep. 2016 Sept-Oct;15(5):320-4.

FIGURE 2: MOST COMMON LOCATION OF A CALF STRAIN

Diagnosing a calf strain

Calf strains may be minor or very severe. A physiotherapist will typically grade the injury as shown in box 1. In a grade-1 strain, the midpoint of the calf may be painful to the touch. Pointing the foot (plantar flexing) reproduces the pain. A grade-I injury feels like a sore, strained, or pulled muscle, without swelling, bruising, or disruption in function. Athletes with grade-II partial tears will experience swelling, bruising, and possibly have difficulty walking. A visible bulge in the middle of the calf where the muscle retracts toward the Achilles’ tendon signifies a grade-III complete rupture, which is a much more severe injury requiring months of rehab and possibly, surgery. These days, sports doctors largely rely on ultrasound imaging to diagnose and grade calf injuries accurately.

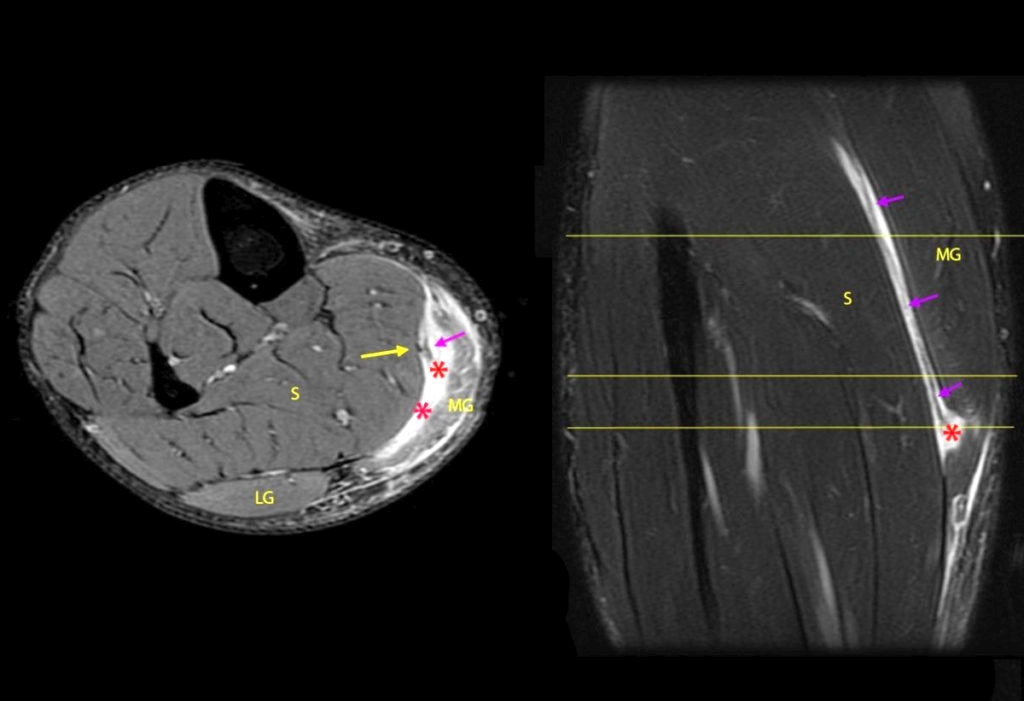

While diagnosis can be made by a clinical examination, this is not always reliable; one study conducted at the University Hospital of Rijeka found absolutely no correlation between the patient’s history or clinical exam, and the extent of injury diagnosed by ultrasoundMedicina Fluminensis. 2012 Dec;48(4):497-503. In other words, estimating the extent of damage to the muscle based solely on what the clinician sees and feels isn’t always accurate. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be used to image and diagnose a calf strain (see figure 3). However, an advantage of ultrasound over MRI is that it can be conducted during the initial consultation, which means it costs less, and gives immediate results. Also, since ultrasound can easily be carried out repeatedly over a period of time, it provides a good method of monitoring recovery.

Calf pain can also be referred from other injured muscles, such as the popliteus muscle, which runs behind the knee, or muscles embedded more deeply in the leg. Other ailments that cause calf pain include compartment syndrome, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), popliteal artery entrapment syndrome, or a ruptured Baker’s cyst behind the knee. Compartment syndrome and DVTs can threaten both life and limb, therefore, calf pain should NEVER be ignored. You should always consult a doctor if any calf pain does not improve with conservative treatment, or if you experience any numbness and tingling.

BOX 1: CALF STRAIN GRADING

GRADE 1

The muscle is stretched causing some small micro tears in the muscle fibres. Recovery takes approximately 2 to 4 weeks if you do all the right things.

GRADE 2

There is partial tearing of muscle fibres. Full recovery takes approximately 4 to 8 weeks with good rehabilitation.

GRADE 3

This is the most severe calf strain with a complete tearing or rupture of muscle fibres in the lower leg. Full recovery can take 3-4 months and, in some instances, surgery may be needed.

FIGURE 3: MRI SCAN OF GASTROCNEMIUS TEAR

A tear in the medial gastrocnemius has created a large gap (white space marked by red asterisks) which extends partially through the lower portion of the muscle belly. This tear is broad, extending across the medial gastrocnemius to near the lateral gastrocnemius. A vertical split extends upward, visible on the right hand image (shown by purple arrows).

Treatment

The good news is that many calf injuries respond well to conservative treatment – ie without the need for surgery. For a grade-I injury with soreness and no swelling, treatment with icepacks and a few days of rest should clear things up. To avoid progressing to a grade-II injury however, you will need to follow up with some appropriate stretching and exercise (see later).

If you’re unfortunate enough to suffer a grade-III injury, it may be difficult to walk at all. Initially, you should follow the ‘RICE’ protocol – rest, ice, compression, elevation (figure 4) - for several days:

- Begin by applying icepacks for 15-20 minutes every couple of hours as soon as possible following injury.

- You can also compress the calf using a compression wrap. Begin at the toes and wrap all the way to the knee, removing for a 15-minute break every couple of hours.

- Elevate the injured leg up on pillows or a stool when sitting.

- While it’s best to rest the leg, you can use crutches if need be to help avoid weight bearing. Be aware that the fluid from the leg drains to the ankle; don’t panic if you notice swelling and bruising in the ankle after a day of being up and about.

FIGURE 4: RICE PROTOCOL

After the first few days of acute management, try walking in a shoe with a small heel, or insert a heel lift into a shoe. This takes the tension off of the calf muscles. Heel lifts may be used up to 12 weeks after the injuryCurr Sports Med Rep. 2016 Sept-Oct;15(5):320-4. Continue to wear a sports calf compression sleeve or compressive wrap to control the swelling and provide comfort. In order to ensure your compression wrap is effective, look for those that provide around 20-30 mm Hg of compression. Limited evidence shows that wearing these wraps can improve recovery time by up to seven daysCurr Sports Med Rep. 2016 Sept-Oct;15(5):320-4. Practitioners at the Institute of Sports Medicine in Sydney have also established that early initiation of physiotherapy treatment for calf injuries brings about better recovery results. In a retrospective look at 720 patients with calf strains over 12 years, those who began treatment within the first 48 hours after injury recovered, on average, in nine days – faster than those who delayed treatmentAm J Sports Med. 1979 May-Jun;7(3):172-4. All were treated with a regimen of pain relief with modalities like ice and ultrasound, followed by passive stretches and muscle strengthening – but this study did not specify the specific muscle or grade the level of injury.

There’s little evidence for using more exotic therapies, such as platelet rich plasma or stem cell injections, in calf strain injuries. Besides, calf strains respond so well to conservative treatment that there seems no need to further investigate this issue. To underline this, consider a retrospective study conducted at the Nanjing University Medical School, where the researchers followed 36 subjects with calf strainsMinerva Orto Trauma. 2014 August;65(4):265-270. Each subject was prescribed an initial treatment protocol of RICE; then hot compresses for three days, with leg compression using bandages; and weight bearing as tolerated. Nearly all (91.8%) of the subjects returned to their prior levels of activity level by four months after the injury. The remaining three patients required surgery to correct their tear. Surgical intervention should therefore be considered a last resort, and will more likely be required in complete ruptures.

Suggestions for initial calf strain treatment

Calf injuries can be sudden and inconvenient. Here’s how to initiate treatment at home (based on the Sydney model Am J Sports Med. 1979 May-Jun;7(3):172-4), until you can seek further intervention:

- *Begin applying icepacks to the area for 20 minutes at a time and follow with passive calf stretches using a towel or Theraband as illustrated below.

- *Hold the stretch (to the point of discomfort but not pain) for 10 seconds and rest for 10 seconds. Repeat this cycle for 10 minutes.

- *Then, in the same position, actively pull the toes back toward your nose, holding for three seconds and resting for three seconds, for 10 minutes.

- *Next, point your toes as best as you can and hold for three seconds, then rest for three seconds, again for 10 minutes total.

- *Follow with the RICE protocol, repeating the intervention one to two more times each day for the first few days.

The whole aim of early treatment is to limit swelling and bruising. Therefore, avoid using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications for pain relief, as these can promote bleeding.

INJURY PREVENTION

The best way to prevent a calf injury is to maintain good calf strength and flexibility, both easily done on a set of steps. Stand with heels hanging off of the step and slowly lower both heels down. Hold the stretch for 10 seconds then level off and repeat, a total of five to ten times. When this is comfortable, try performing the same stretch standing on one leg. Isolate the soleus muscle by bending the knees while in the stretch position.

To gain strength, rise up on toes and lower (see below), repeatedly for two to three sets of 10-25 reps. Progress exercise by performing the same on a single leg. Incorporate this into normal training two to three times per week for optimal muscle strength and flexibility.

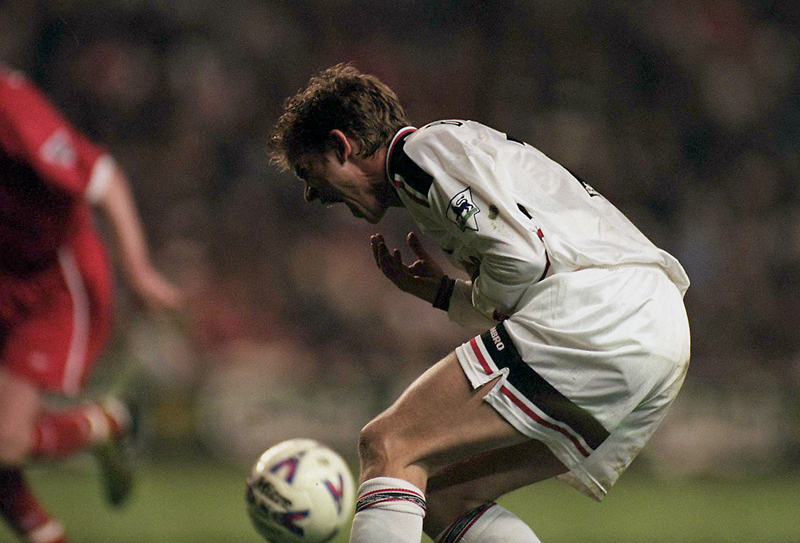

CASE STUDY: Gareth Bale

In 2017, the Welsh football star Gareth Bale spoke out about his ongoing struggle with calf injuries. His troubles began during his initial 2013-14 season with Real Madrid. After sitting out most of the preseason due to contract negotiations, he tweaked a calf muscle during a warm-up session. Just a few weeks later, he went down with a strain to the other calf, and missed the next month of play. Later that season, he suffered trauma to the leg when was accidently kicked by a team member and missed further play time.

Early in the 2015-16 season found Bale again battling calf injuries to both legs. Then midseason, he was downed with a traumatic ankle injury. Just four months after the surgical repair of that injury, he was clutching his calf again. The cause of his woes seems to be a recurrent soleus strain. In an interview with Spanish newspaper, El Pais, Bale admitted that in order to play, he had to take a lot of painkillers www.express.co.uk/sport/football/852616/Real-Madrid-News-Gareth-Bale-injury. “Maybe on reflection, I should have taken more time to recover”, he said.

Endurance athletes such as distance runners can learn from Bales’ struggle. Firstly, calf muscles require great care, especially in later years. This means you should continue calf strength and flexibility exercises even during the off season or any injury recovery period. Calf muscles can take up to four months to fully heal; be judicious therefore about when to return to sport. Incorporate calf flexibility and strengthening exercises into a regular training programme to prevent further injury.

Summary

Calf strain can strike athletes in all sports, but it is particularly common in male runners in midlife. Calf strains vary from minor grade-I strains to complete grade-III tears. Most often the tears occur in the medial head of the gastrocnemius. Athletes typically respond well to conservative treatment measures to manage swelling, bruising, and pain. Progressive stretching and exercise ensure that the athlete returns to full function with adequate flexibility and strength, usually within four months.

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.