You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Pain: submit or conquer?

Is it ever safe to ‘work through’ the pain of an injury and if so, when? Trevor Langford provides the answers

Is it ever safe to ‘work through’ the pain of an injury and if so, when? Trevor Langford provides the answers

Pain can present in different ways with varying types, locations and intensities and is a unique sensation for each and every one of us. Pain while training can create feelings of fear and frustration - of missed training sessions and the inability to participate in sports. But there is another side to pain as it can also be perceived as a positive form of sensory feedback, informing you about your condition and the stage of healing. This feedback can be utilised in order to promote injury rehabilitation.

So what are the different types of pain and when and how should we work into it? This article aims to provide some useful pointers, with the caveat that you mustn’t forget the importance of effective rehabilitation to restore normal function, as guided by a physiotherapist.

What is pain?

Pain can be derived from many different body parts and not necessarily from the muscular and skeletal systems. Generally speaking however, pain is the response of pressure on nerve endings, which is felt at a particular site in the body as a result of inflammation or from painful stimuli. The nervous system is highly sophisticated in relaying information when something is dangerous – for example if we touch something sharp or hot. It is a warning to us that we should not do that. Therefore, although pain isn’t a pleasant experience it is a highly effective feedback system to inform us of the intensity of an injury.

By the same token, we can use pain as a ‘positive reinforcement’, allowing us to return to normal function by working within pain parameters, but also loading body tissues to promote healing. Having said that, it is essential to determine the cause of pain (and also the severity of the injury) before rehabilitating an injury. This will determine the best treatment path during rehabilitation, and the timescales needed for return to sport.

Types of pain to load

Pain is a broad umbrella term for multiple sensations (see figure 1). Some painful conditions can be worked into during rehabilitation, while some may require further investigations. If you feel muscle fatigue throughout the whole area of a muscle it is fine to continue to load that area. If you however have point specific sharp pain within in a muscle, then this is an indication that a muscle strain may be present and the load should be reduced with an ice pack applied.

Figure 1: Different pain types

If you have joint stiffness as a result of a muscle spasm or following a period of inactivity, it is essential to mobilise the joints by simple joint movements and reduce the muscle spasm through foam roller and mobilising exercises. By improving joint movement and function, pain can not only be reduced but also give an increased feeling of ease of movement especially on other surrounding joints too. It is essential to do frequent exercises as often as five minutes every hour and not just during the five minutes before training. Exercising frequently can help to reduce pain levels, which can prevent joints from becoming stiff and muscles shortening. This in turn helps manage inflammation, which can also contribute to pain levels.

If pain presents as shooting pain, tingling or numbness, then this could indicate a nerve entrapment or other spinal pathology. This will warrant further investigation and you should consult a physiotherapist to assess your spinal movements first before progressing with exercise therapy. He or she may recommend a referral for a scan. Any issues involving low-back pain with accompanying bladder or bowel dysfunction and/or numbness around the inner thigh area warrants immediate investigation at an accident and emergency department.

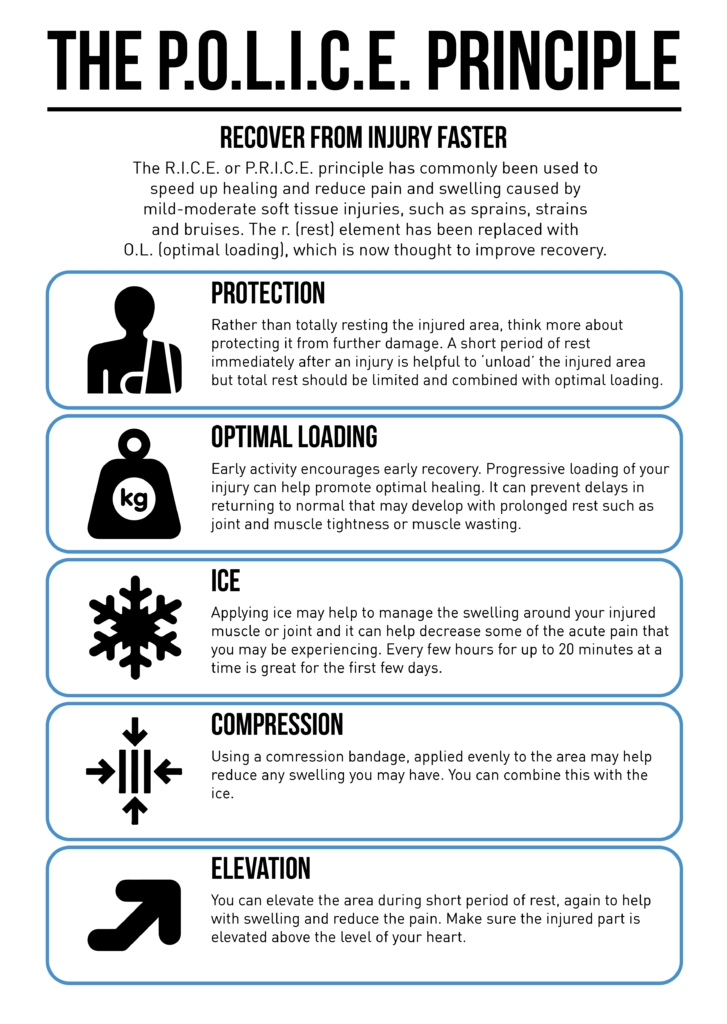

Figure 2: The police principle

Pain during exercise

Rest has previously been widely advocated in order to treat injuries, and has formed part of the acronym ‘RICE’ which relates to ‘rest, ice, compression and elevation’. An acronym currently more favoured within the world of sports injury management is ‘POLICE’. This relates to protection, optimal loading and followed by the wellknown ice, compression and elevation (see figure 2)(1).

A sports physiotherapist can guide you as to how much load you can optimally apply to an injured muscle or joint system to encourage and promote healing. During rehabilitation, you are required to work to a specific level. This level is one that provides just enough stress to encourage a healing response, which then reduces the risk of tissue breakdown once training has resumed.

To optimise the strength and stability of a joint and its surrounding muscles/tendons, it is essential to restore pain-free range of motion whilst also managing signs and symptoms of inflammation too (see table 1)(2). As you start to load the involved limb, you will likely notice (depending on factors such as time since injury, your pre-injury conditioning and severity of injury) a strength and muscle length deficit in the surrounding tissues. As you work to improve the strength and length of the surrounding muscles, you will likely experience muscle fatigue, which may be perceived as pain. To rehabilitate an injured body part, you will have to work hard through the fatigue barrier in order to restore sufficient strength to meet the physical demands of your sport.

Table 1 Pain and appropriate phases of rehabilitation

| Increase concentration | During this period of relative tissue inactivity, the primary goal is to protect the injury site whilst reducing pain and inflammation – also to prevent strength depletion with ‘optimal loading’ and restoration of joint range of motion. To achieve this, pain will have to be tolerated within safe limits. To move onto phase two, you should have 75% joint range of movement of the non-involved side plus minimal pain while performing all exercises in this phase, with good muscle activation. |

| Phase two of injury rehabilitation | This phase should aim to continue to protect the injured body part whilst continuing to improve strength and functional stability. Loading can be increased and it may be necessary to apply ice at the end of rehabilitation sessions, if ice or pain are present. To move onto phase three, you should have full range of movement, and 60% of the strength levels of the uninvolved side. |

| Phase three of injury rehabilitation | During this phase, an emphasis should be placed on restoring muscular strength and endurance with a progression of cardiovascular fitness and stability. To move onto phase four of the rehabilitation programme, you should have 70-80% strength of the uninvolved side and the ability to execute drills specific to the demands of your sport, with pain-free control of the entire body. |

| Phase four of injury rehabilitation | The aim of this stage is for a return to pre-injury fitness and re-integration into full training by restoring fitness and conditioning with skill acquisition to meet the demands of the activity. |

| NB: During early rehabilitation, ice can be useful to manage pain and inflammation following exercise. This allows body tissues to be loaded, stimulating healing but without excessive inflammation. | #colspan# |

Figure 4: The negative spiral of pain and inactivity

Scar tissue

Scar tissue is laid down during healing of a tendon or muscle injury. To encourage the scar tissue to become as strong as the surrounding tissues, it should be ‘optimally loaded’ as directed by a therapist to prevent further soft tissue breakdown from occurring. Figure 4 provides a cyclical system of tissue breakdown with the outcomes if an injury isn’t managed correctly.

A prime example of how injuries can lead to breakdown is the way lower-back injuries were poorly managed in the past with bed rest and inactivity. Modern treatment techniques for lower-back disorders however promote movement to engage the surrounding core muscles and to mobilise the joints. This principle can be applied to all joints of the body in activating specific muscles to promote joint stability and fine muscle control.

Don’t fear DOMS

DOMS is an abbreviation for ‘delayed onset muscle soreness’, which is a natural physiological response to exercise overload. When we exercise and stress our muscles above and beyond what they are used to, muscle soreness can occur, which peaks 24-36 hours after. Some people may be put off by rehab by DOMS, fearing it as an exacerbation of their injury. In fact, DOMS (resulting in tight achy muscles) is a positive outcome following exercise. Moreover, the discomfort of DOMS can be eased by movement and light exercise. However, in symmetrical sports such as running, DOMS is usually found on both sides of the body; if there is localised soreness or pain on just one side of the body, this may indicate a muscle strain - unless of course very single sided sport such as rowing (as opposed to sculling) has been undertaken.

DOMS is a pain that should be ‘worked into’, which will help ease discomfort. Good ways to do this include gentle cycling, walking, foam roller exercises, massage and stretching(3). Using these approaches, DOMS will settle down relatively quickly. However, it should be noted that overloading an already fatigued muscle may result in soft tissue breakdown. This shouldn’t deter you from further exercise, but you should adjust (lower) the frequency, intensity and duration until the DOMS has passed.

Key points

- Pain can be thought of as a positive form of feedback, giving an insight as to the stage of healing

- A weak approach to rehabilitation with too much rest can result in soft tissue breakdown and prolonged periods of time in the treatment room.

- During early injury rehabilitation, pain should be minimised by ‘optimal loading’ exercises specific to the nature of the injury

- To achieve full rehabilitation, expect to work to the point of muscle fatigue whilst also adopting recovery techniques to prevent injury breakdown.

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.