You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Swimmer's shoulder: the fast lane to recovery!

Up to 90% of swimmers will experience shoulder pain at some point in their swimming careers. Andrew Hamilton looks at injury rehab recommendations and in particular, the need for an appropriate return to swimming programme in the pool...

Although swimming is a relatively low-risk sport for injury, shoulder pain is surprisingly common in swimmers. Various studies show that over a career lifetime, between 40% and 91% of swimmers will suffer a swimming-related shoulder injury(1-4). However, when you consider that elite swimmers may be racking up over 10km in the pool each day, and that the arms are the prime generators of forward thrust, we should perhaps not be surprised. High volume training can lead to muscle fatigue of the rotator cuff, upper back, and pectoral muscles, which in turn may result in microtrauma due to the decrease of dynamic stabilisation of the humeral head(5,6).Aetiology of shoulder injury in swimmers

To appreciate the vulnerability of a swimmer’s shoulder to injury, it helps to understand the biomechanics of the stroke cycle. Since freestyle is the most commonly used stroke (for example, the stroke of choice in related sports such as triathlon) we will focus on this style. The freestyle stroke consists of four distinct phases, which are shown in figures 1-4 below:Figure 1: Hand entry

Figure 2: Early pull through

Figure 3: Late pull through

Figure 4: Recovery

In freestyle swimming, each of these phases has the potential to increase the risk of shoulder injury when executed incorrectly. Some of the common errors are as follows:

- *Hand entry - the swimmer’s hand enters the water either medial or lateral to the ideal line (with the swimmer’s head representing 12 o’clock, a right hand should enter the water at approximately one o’clock and a left hand at 11 o’clock). A deviation either way increases stress on the rotator cuff.

- *Early pull through– a ‘dropped elbow’ (where the elbow is lower than the hand while the arm pulls under the body) will fail to fully engage the latissumus dorsi muscles, which can increase the risk of impingement. It also inhibits a smooth, symmetrical body roll, which is needed to decrease stress on the rotator cuff muscles and to keep the scapula appropriately anchored on the thorax.

- *Straight arm recovery– a fully extended elbow while the arm is out of the water in the recovery phase is another common error. During this phase, a bent elbow is much preferred because it reduces the amount of stress on the rotator cuff.

Land-based prevention and rehab training

Studies suggest that an endurance training and strengthening program for the shoulder and periscapular muscles, with emphasis placed on the serratus anterior, rhomboids, lower trapezius, and subscapularis, may help prevent injuries and speed recovery when injury does occur(9,10). There’s also evidence that abdominal and scapular muscle strengthening performed in dry-land training can yield benefits; in particular, the goal of core and abdominal strengthening is to develop increased control of the pelvis by avoiding excessive anterior pelvic tilt and lumbar lordosis(11,12). Table 1 shows some example of some commonly-used dry-land training exercises that meet these criteria.Table 1: Dry-land strength training(13)

Muscle group |

Examples of training exercise(s) |

Primary rotator cuff muscles(performed in standing position, scapulae maintained in retraction) |

*External rotation using Thera-Band—facilitates bilateral strengthening. Strengthens: Teres minor. *Straight arm lifts. Strengthens: Supraspinatus *Ball on the wall—one arm extended, rolling a ball in circles. Strengthens: Stabilizers of the rotator cuff and scapulae |

Scapular muscles |

*Seated row using Thera-Band®—scapulae maintained in retraction using looped Thera-Band. Strengthens: Rhomboids *Straight arm reverse arm lifts — performed lying on the stomach, arms fully extended at shoulder height, palms down, and lifting arm away from the floor; initially, only the weight of the arm is used, but as strength develops, 0.5 or 1.0kg weights may be used. Strengthens: Teres minor, rhomboids *Variable position push-ups — initially performed against a wall while standing, then on the knees, finally in a traditional push-up position. Strengthens: Serratus anterior |

Abdominal and lower back muscles |

*Supine flutter kicking — performed lying flat on the back with hands under the pelvis back lightly “flutter kicking” the legs before progressing to a similar motion with the arms. Strengthens: Abdominal muscles *Kneeling diagonals — performed in a kneeling position with upper body level to the floor and hands touching the floor with the back kept flat; the right arm and the left leg are lifted and held for 1 second, then the contra-lateral sides performed in an alternating pattern; exercise can be performed with eyes closed, which emphasizes the use of the postural muscles to a greater degree to develop balance and stability. Strengthens: Lower back |

Returning to swim training

Much has been written about pain management and dry land rehab training following shoulder injury. However, the successful return to pain-free swimming training in the water presents a major challenge. All too often, symptoms improve or resolve after rest and dry-land training, only to recur once the swimmer is back in the pool. The particular hurdles that need to be overcome at this stage are ironing any stroke imperfections while building up swimming training volume gradually and without overload.The use of equipment: yes or no?

The use of swimming aids to develop strength and power is commonplace in the competitive environment. However, when returning to the pool after a shoulder injury, some aids are contraindicated:- *Kickboards - used to focus on kicking only. These are most commonly used with arms extended in front of the body, which increases loading on the shoulder and therefore best avoided in all cases of injury;

- *Pull buoys – used to focus on arm stroke only. The pull buoy is placed between upper legs to prevent kicking while providing buoyancy to the lower body. Because the workload performed by the upper body is increased, pull buoys may be contraindicated in cases of shoulder tendinitis/tendinosis;

- *Paddles – coming in a variety of sizes, paddles are worn on the hands to increase surface area of the hand, which slows down the pull and increases the ‘feel’ of the water while building strength. The increased loading with paddles make them unsuitable in all cases of shoulder pain and injury, especially where stroke technique is less than perfect.

There are two key criteria that need to be achieved before a swimmer can begin a return swimming programme: firstly, the swimmer should be nearly pain free in the shoulder complex and be able to achieve full active extension and external rotation of the glenohumeral joint. Secondly, the strength of the rotator cuff and scapular stabilising muscles should be scored at 5/5 when tested using traditional manual muscle testing(14,15). This is a test that he physiotherapist will be able to carry out.

Dry-land training performed regularly is generally very effective at getting the swimmer to this point. However, it is important for coaches and/or physiotherapists to appreciate that simply handing the swimmer back to the coach without any further support or advice risks further setbacks as the predisposing factors to injury may still be present. A preferred approach is collaboration with the coach to ensure the subsequent training is both measured and appropriate.

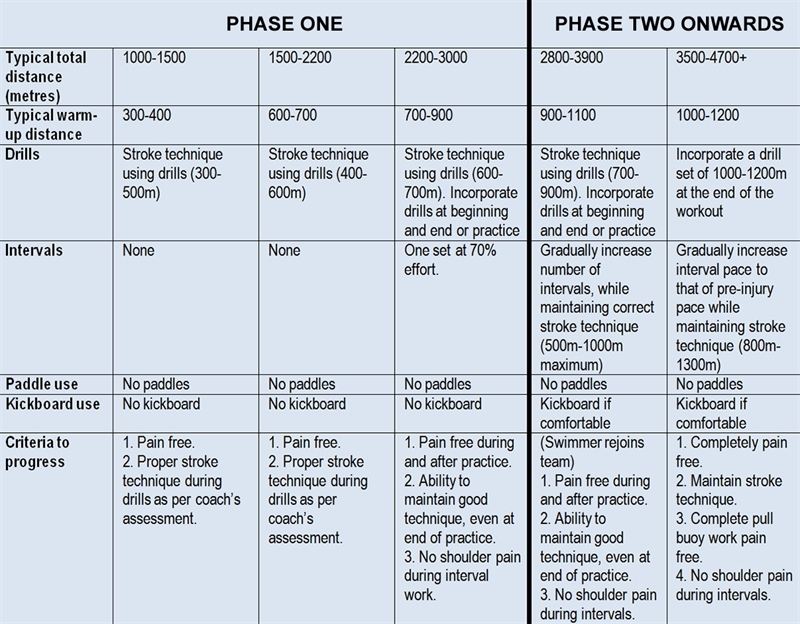

In an excellent paper on this topic, Spigelman et al suggest a two-phase approach(16):

- *Phase 1 – initially focuses on stroke technique drills to prevent the swimmer from reverting to bad habits that could reinjure the shoulder. During this phase, the distance covered in the pool increases only in small increments to prevent overuse and to allow assessment of how the shoulder is coping with the resumption of training;

- *Phase 2 – once the swimmer has successfully completed phase 1, the focus switches to interval work, which is designed to help build the swimmer’s muscular and cardiovascular fitness levels. During this phase, weekly distance increases in larger increments in order to help build endurance – BUT ONLY if the swimmer can demonstrate that he or she can tolerate longer practices.

Talk to me!

If follows from the above that good communication is required, both between the swimmer and coach, and between the coach and physiotherapist. Coaches need to communicate with the swimmer the importance of providing constant feedback about how their shoulder is responding to the increasing training load. Swimmers meanwhile need to understand that any symptoms of pain or discomfort need to be reported immediately so the coach can pause the training if necessary and evaluate the situation. A useful tool in this respect is the ‘Swimming Soreness Rules’, which can help swimmers recognise pain, and the coach/physio adjust the swimming portion of shoulder rehabilitation in the swimmer’s programme(16). These rules are shown in the panel below.Panel: The ‘swimming soreness rules’

- So long as no soreness manifests, increase the total swimming distance by 200-300m per day;

- If the shoulder is sore during the warm up but the soreness has gone within the first 500-800m of training, repeat a similar workout from the previous day. If the shoulder becomes sore during this workout, cease the workout and take two days off. When returning to the pool, decrease the distance of the session by 300m compared to the last pain-free workout;

- If the shoulder is sore for more than one hour after swimming, or the next day, take 1 day off and repeat the most recent swimming workout;

- If the shoulder is sore during the warm up and the soreness hasn’t gone within the first 500-800m of training, stop immediately and take two days off. When returning to the pool, decrease the distance of the session by 300m compared to the last pain-free workout.

- If soreness occurs repeatedly despite this graduated return to training, a further evaluation should be made by the physiotherapist.

Criteria for progression

A detailed description of suitable drills and swimming workouts for the swimmer returning to the pool is beyond the scope of this article and will of course depend on the swimmer in question, his/her event, stage of development etc. However, the general criteria for progression from phase 1 to phase 2, and from phase 2 to resuming event-specific training is that progression should only be very gradual - you can find some examples in table 2 below. The key point is that any increases in pain, soreness or discomfort need to be recognised by the swimmer and coach as potential warning signs to decrease or even suspend training while re-evaluation takes place.Summary

Overuse injuries to the shoulder are all too common in competitive swimmers, especially where training volumes are high and stroke technique is less than perfect. Evaluation by a physio/clinician, rest and appropriate dry-land strengthening exercises are an important first phase of any recovery programme. However, the process of rehab shouldn’t stop there.The first few weeks in the pool as part of a return to swimming programme are vitally important for a full recovery, and this is a time when cooperation between the swimmer, his/her clinician and the swimming coach can be extremely useful. During the return to swimming programme, any increase in workload should only be very gradual with an emphasis on correcting any stroke errors rather than rushing the swimmer back to full race fitness. A key part of this process is constant monitoring of and feedback from the swimmer so that the coach and physio can make any adjustments to the programme as needed.

Table 2: General criteria for progression

References

- Clin J Sport Med. 2010;20(5):386-390

- Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(2):254-260

- Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2007;17(4):373-377

- Clin Sports Med. 1999;18(2):349-359

- Orthop Clin North Am. 2000;31(2):247-61

- Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(2):105-113

- Am J Sports Med. 1993;21(1):67-70

- Clin Sports Med.2001;20(3):423-438

- Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(6):569-576

- Rodeo SA. Swimming. In: Krishnan SG, Hawkins RJ, Warren RF, eds. The Shoulder and the Overhead Athlete. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & WIlkins; 2004:350

- Phys Sportsmed. 2003;31(1):41-46.

- Kibler WB, Herring SA, Press JM. Functional Rehabilitation of Sports and Musculoskeletal Injuries. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers; 1998

- Sports Health. 2012 May;4(3):246-51

- J Chiropr. 2004;41(10):32-38.

- Kendall FP, Kendall FP. Muscles : testing and function with posture and pain. 5th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005

- Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014; vol 9 (5) 712

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.