You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Triathletes and injury risk: will you stay injury free next season?

What are the major risk factors for injury when training for a triathlon, and what can triathletes do to minimise the chance of sustaining an injury? Andrew Hamilton looks at what the science has to say

At this time of year, most athletes are enjoying a bit of downtime – an essential part of ensuring some deep rest and recovery. However, it won’t be too long before the days start to stretch out, which means that the time of year for cranking up your training volume and building base endurance will soon be upon us. However, with an increase in training volume comes an increased risk of injury. For triathletes who perform high training volumes, the stresses and strains of triathlon training tend to be dissipated more evenly across the muscles and joints of the body than in single-sport athletes, which helps to lower the risk of injury. However, research indicates that injury rates among triathletes are still surprisingly high, and that chronic overuse injuries are particularly problematical.Norseman Xtreme Triathlon

In a very large and carefully designed study, Norwegian researchers followed 875 triathletes during their early-season training period, including 174 participants in the Ironman-distance Norseman Xtreme Triathlon during their 26 weeks of training prior to the event(1). In particular, they wanted to investigate the rates of acute and overuse injuries, as well as days lost through illness. Data on overuse injuries affecting the shoulder, lower back, thigh, knee and lower leg were collected every second week while illnesses, acute injuries and overuse problems affecting other areas were also recorded.The results showed that overuse-type injuries affected no less than 56% of the triathletes and the most prevalent sites of overuse problems were the knee (25%), calf and Achilles tendon (23%) and lower back (23%). Of these, 165 triathletes (20%) were classed as having ‘substantial overuse’ problems – ie severe enough to result in a week or more of lost training time. The risk of acute injury however was far lower – just 36 cases (4%), these being mainly contusions, fractures and sprains affecting knee, shoulder/collarbone and sternum/ribs, suggesting falls or collisions (most likely sustained on the bike). Illness meanwhile affected 156 triathletes.

These results tie in neatly with those from a previous, smaller Australian study on 131 triathletes(2). This found that no less than 50% of the triathletes sustained an injury in the 6-month preseason build up, while 37% were injured during the 10-week competition season. Once again, it was overuse injuries that dominated, accounting for 68% of preseason and 78% of competition season injuries reported.

Factors in injury

What are the main risk factors for picking up an overuse injury in triathlon? Well, research shows that increasing age, high running mileage, increased triathlon training distances, a history of previous injury, and inadequate warming-up and cooling-down procedures all increase injury risk(3). There’s also evidence that poor technique and biomechanical imbalances are significant risk factors, and that high running mileage in the off-season is strongly linked to injury during the following competitive season.Risk of sudden change

The above injury-risk factors are subject to a caveat however. Although there is an association between high training loads and injury risk, new research suggests that possible of even greater importance is the rate of CHANGE in your training load. A brand new study published last month looked at the main factors associated with an injury (or condition that caused pain) in triathletes (along with other endurance athletes such as runners, swimmers and cyclists)(4). It found that the lowest injury rates were in athletes who maintained consistent, moderate to high training loads, but importantly, avoided sudden increases in acute training loads – ie avoided sudden spikes in training volume or intensity or both. However, in those athletes who had suffered an injury in the previous 12 months, high training loads did increase the risk of an injury, even when training load spikes were avoided – ie if you have a recent history of injury, high-volumes of training could put you at risk of another, even when you build up very gradually.Acute to chronic work ratio

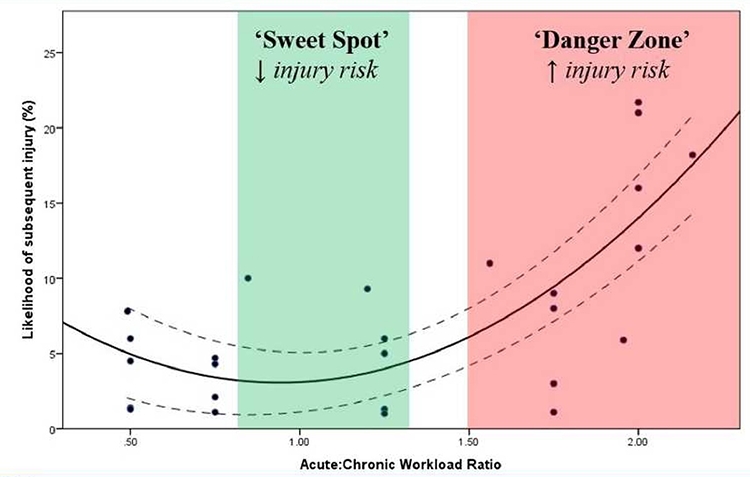

High-performance coaches and the sports medicine world have recently developed some clever scientific studies that show exactly how ‘spikes’ in training volume and/or intensity can lead to injuries. The tool used in this context is the ‘Acute to Chronic Work Ratio’ or ‘ACWR’. The ACWR uses a rolling 4-week average to determine the chronic workload (some use a 3-week average) and the following week’s load (acute load) is compared against the average of the preceding four weeks. If the ratio of the acute (what you’ve just done) to chronic (what you’ve done in the four weeks prior to that) workload is greater than 1.3 or less than 0.8, then this may set up the athlete for an injury in the following weeks (see figure 1).Figure 1: Risk of injury relating to ACWR(5)

Thick black line shows % risk of subsequent injury. The green zone represents an ACWR of 0.8-1.3. (NB – injury risk may increase when the ACWR drops below 0.8 because although the workload is reduced, too large a drop can result in deconditioning, which may increase injury risk at a later date when workload increases again).

Practical advice for triathletes

So how can triathletes reduce the risk of injury as they build up for the coming season? Here are some useful tips:- Always warm up and cool down thoroughly before/after each session.

- Increase your training volume or intensity only very gradually, and schedule in regular ‘easy’ weeks during any build-up phase.

- NEVER increase training volume and intensity together.

- ALWAYS monitor your ACWR and avoid straying above a ratio of 1.3 (for a more detailed explanation with examples of how to monitor ACWR, see this article.

- Choose your running shoes carefully, on the basis of your biomechanical needs and replace them regularly.

- Ensure your bike set-up is optimised to your biomechanical needs. This might involve experimenting with different stem and handlebar lengths and heights, saddle positions, crank lengths and even frame geometries.

- Perform regular strength and flexibility training to build shoulder, quadriceps and calf resilience (the most vulnerable areas). Regular core work is also recommended for lower back health.

- Br J Sports Med. 2013 Sep;47(13):857-61

- J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003 Apr;33(4):177-84.

- Int J Sports Med. 1998 Jan;19(1):38-42

- Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2018 Nov 14:1-28

- Br J Sports Med. 2016 Apr;50(8):471-5

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.