You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Rhodiola rosea: a rosy prospect for athletes?

Sports Performance Bulletin looks at the evidence for and against the benefits of the herb Rhodiola rosea. Can it enhance performance, and should it be considered for performance enhancement?

Rhodiola rosea, which is also known as golden root, rose-root and arctic root, is an antioxidant-rich plant that grows in cold regions of the world. Rhodiola has reportedly been used for centuries by inhabitants of the Arctic regions to help cope with the severe cold and stresses that living in such a climate inevitably brings. This ‘fatigue-fighting’ reputation inevitably resulted in Rhodiola coming under the scientific spotlight. However, up until around 2010, most of the scientific research into Rhodiola’s properties was focussed on its apparent ability to exert anti-fatigue effects, increasing mental performance, and particularly the ability to mentally concentrate(1-4) - and little attention was paid to its potential to enhance sports performance. During that period, there was also an increasing body of evidence that Rhodiola might be able to exert an antidepressant effect in subjects with mild to moderate depression(5-7).Performance and mind connection

More recently however, there’s been a growing interest in the potential of Rhodiola to produce physical benefits – in the context of exercise. This was inevitable; with a growing realization that mental fatigue and physical performance during exercise are intimately connected (which is after all how caffeine exerts its considerable ergogenic effects), studies soon got underway to investigate whether Rhodiola might improve athletic performance.One of the early human studies looked at rowing performance, antioxidant status and muscle damage(8). International, elite rowers who consumed 100mgs per day twice daily of Rhodiola showed an improved antioxidant status compared to their counterparts who consumed a placebo. However, when it came to markers of muscle damage in the rowers, the Rhodiola supplementation seemed to offer no benefits. This was in contrast to two animal studies published the same year, which found that when rats were given Rhodiola supplementation, they not only experienced improved biochemical markers related to exercise performance, their tolerance to exhaustion in a swimming performance test was also significantly improved(9,10). This all goes to show of course that it’s unwise to assume findings in animal studies will always be replicated in humans!

Rhodiola and sub-maximal exercise performance

The Rhodiola story went quiet for a while but in 2013, US researchers looked into the effects of Rhodiola on cycling endurance performance as well as levels of perceived exertion, mood, and cognitive function(11). In this study, eighteen subjects performed two 6-mile time trials on two separate occasions. On one occasion, randomly chosen subjects took 3mgs per kilo of bodyweight of Rhodiola one hour before the test while the others took an inert placebo pill an hour before. On the second occasion, subjects who had taken Rhodiola then took the placebo pill, while those who had taken the placebo in the first trial switched to the Rhodiola for the second. Importantly, neither the subjects nor the researchers knew whether the Rhodiola or placebo had been taken before either of the tests. This kind of scientific trial is known as a double-blind, random crossover trial – important because it is considered the most rigorous and reliable of the lot.The test consisted of a standardized 10-minute warm up followed by a 6-mile time trial on a bicycle ergometer. Rating of perceived exertion (RPE) was measured every five minutes during the time trial using a 10-point Borg scale. Before the warm-up, two minutes after the warm-up, and two minutes after the time trial itself, the researchers also checked blood lactate concentration and salivary cortisol (providing a measure of ‘physiological stress’). The findings were as follows:

- *Taking the Rhodiola significantly decreased heart rate during the warm-up (140bpm taking placebo vs. 136bpm taking Rhodiola).

- *Subjects completed the time trial significantly faster when they took Rhodiola; the average time-trial time fell from 25mins 48secs with placebo to 25mins 24secs when Rhodiola was taken.

- *Even though the subjects rode faster when they took Rhodiola, their level of perceived exertion was less than when they rode slower and took placebo!

Seven years of research

Following the US study above, the last seven years have seen significantly more research carried out into Rhodiola and potential performance enhancement. A 2014 study investigated Rhodiola supplementation on exercise-induced muscle damage, delayed onset of muscle soreness (DOMS), and markers of muscle damage and inflammation in 24 experienced male and female runners who completed a marathon(12). The runners were divided into two groups; the Rhodiola group took the herb for 30 days prior to the marathon (and on the morning of the marathon itself), while the control group took an inert placebo. Unfortunately, the results were far less convincing than the cycling study, indicating that Rhodiola did not attenuate the post-marathon muscle soreness or function, nor did it reduce muscle damage or inflammation in the runners.In the same year, another study investigated the effect of taking a single dose of Rhodiola prior to exercise(13). Ten fit males completed two 30-minute cycling trials at 70% VO2max (moderate-intensity pace) following ingestion of either 3mgs per kilo of bodyweight of Rhodiola or an inert placebo. Like the US study above, this was a double-blind, crossover study (ie a rigorous design). During the exercise trial, researchers measured the cyclists’ work rates, heart rates, and perceived levels of exertion. Expired air samples were also taken during the trial to determine substrate utilization – ie what proportion of the energy was being derived from fat, and how much from carbohydrate.

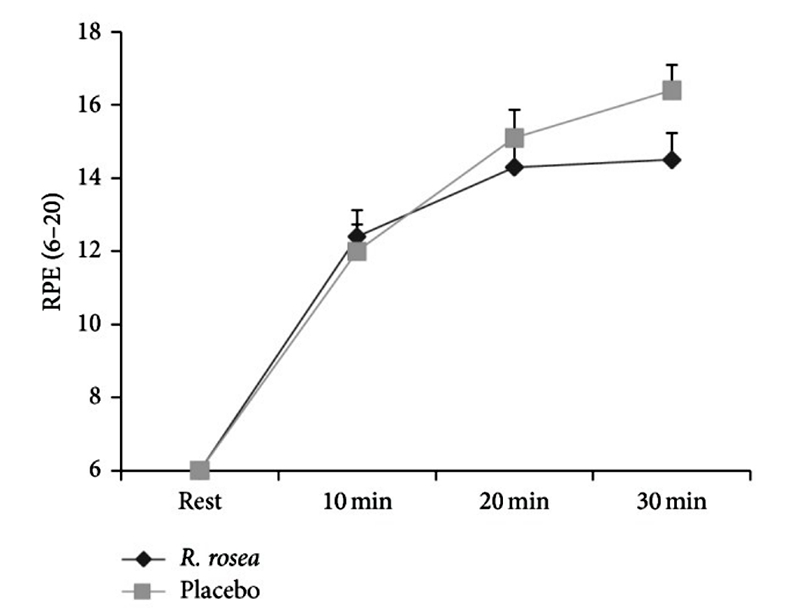

The results showed that there were no significant differences in energy expenditure, heart rates, carbohydrate, or fat oxidation when the subjects took Rhodiola. Interestingly however, when Rhodiola was taken, the levels of perceived effort were significantly reduced (compared to placebo) towards the end of the trial (see figure 1) – as in the cycling trial. Moreover, the subjects also reported significantly higher mood and energy levels in the post-exercise trial period.

Figure 1: Perceived effort during a cycling time trial(13)

Black diamonds show Rhodiola trials; grey squares show placebo trials. Taking Rhodiola reduced perceived levels of exertion during the later stages of the trials, despite identical work rates, heart rates and substrate utilization across both the Rhodiola and placebo trials.

Rhodiola, immunity and heat acclimation

In addition to its potential for enhancing performance, some research has also looked at whether Rhodiola can enhance post-exercise immunity. In a 2015 study by US scientists, researchers investigated if a 30-day period of pre-marathon supplementation with Rhodiola could enhance immune activity – by reducing the magnitude of the post-exercise immune suppression, which is often observed in athletes following an unusually long and/or hard bout of exercise(14). Forty eight runners took part in the study; half took Rhodiola for one month prior to the race while the other half took an inert placebo. After the runners completed the marathon, blood samples were taken at 15 and then again at 90 minutes from the runners and analyzed for the anti-viral activity of various immune components.The results showed that compared to runners taking placebo, in the runners taking Rhodiola, virus replication was suppressed (indicating enhanced immunity). The researchers concluded that the bioactive compounds in the serum of subjects ingesting Rhodiola rosea ‘may have exerted protective effects against virus replication by inducing antiviral activity following intense and prolonged exercise’. Although these results are encouraging, there was no follow up of the runners to see whether those taking Rhodiola experienced a reduced incidence of upper-respiratory tract infections (coughs, colds, sore throats etc), which of course is what really counts. Unfortunately, no further studies have been carried out on Rhodiola and post-exercise immunity, so the question to this remains unanswered for the time being.

Rhodiola is known as an ‘adaptogen’ (a substance that helps the body adapt to physiological stress), and in this context, it has also been investigated for its potential to help the process of acclimatizing to exercise in the heat. In a 2018 study, 20 male subjects completed tests involving walking at 6kmh until volitional exhaustion in a climate chamber (air temperature, 42 °C; relative humidity, 18%) before and after an 8-day heat acclimation period(15). Before each heat acclimation session, half the subjects ingested a single daily dose of 432 mg of Rhodiola, while the other half took a placebo. The results showed that both groups acclimated equally and that taking the Rhodiola produced no beneficial performance, physiological, or perceptual effects.

Rhodiola and anaerobic performance

One of the most recent studies into Rhodiola was carried out last year and looked at anaerobic performance(16). Eleven physically active female college students were supplemented with either 1,500mgs per day of Rhodiola or placebo for three days. The participants also took an additional 500mg dose of corresponding treatment 30 minutes prior to the exercise trials. During each exercise trial, participants completed 3 × 15-second Wingate anaerobic tests, separated by 2-minute active recovery periods. Each exercise trial was separated by a 7-day washout period. Over the 3 × 15-second Wingate tests, average power output, peak power total work performed were all higher when the subjects took Rhodiola.Another recent study investigated the effects of four weeks of Rhodiola supplementation on mental and physical performance, as well as hormonal and oxidative stress biomarkers in 26 healthy young men(17). The subjects received either Rhodiola (600mgs per day) or placebo in a randomized double-blind trial. Prior to supplementation and following supplementation, the students underwent psychomotor tests for simple and choice reaction time, VO2max testing, and blood tests to measure hormonal profiles, as well as the biomarkers of oxidative stress. The results showed that Rhodiola ingestion shortened reaction times and total responses times in the psychomotor test, and produced a greater number of correct responses. But while Rhodiola ingestion raised blood total antioxidant capacity, no changes in endurance exercise capacity and hormonal profiles were observed.

Summary and conclusions

What can we conclude from the research as whole on Rhodiola? There’s no doubt that it can enhance antioxidant activity in the body, and the balance of evidence is quite persuasive that it can reduce the perception of effort, both at moderate and more intense levels of exercise – all without affecting physiological measures such as work outputs and heart rates. It may also enhance immune function, though whether that translates to less illness and infection remains to be determined.As to performance gains, the evidence is mixed. While it exerts a strong antioxidant activity, it doesn’t seem to reduce muscle damage or soreness. However, some evidence suggests that Rhodiola can enhance both aerobic and anaerobic performance, although the evidence is limited and patchy. Why might the results be mixed? One reason is that scientists have yet to identify the active components that might enhance exercise performance. This means that producing a standardized herbal extract containing a known amount of active ingredients is not possible, which in turn means that different studies may have actually been using very different doses of the bioactive ingredients.

Overall, we can conclude that Rhodiola might be worth a try, especially as it is not particularly expensive. Although there are no guarantees of performance benefits, it might help athletes who are in hard training, with busy lifestyles, and who want try and maximize performance and health, and maintain an elevated mood state. However, like all nutritional aids however Rhodiola supplementation is no substitute for getting the nutritional and lifestyle basics correct – a diet based on unprocessed foods - rich in natural carbohydrates, fruits and vegetables, and high-quality proteins – with plenty of fluid and rest and recovery too!

References

- Planta Med. 2009 Feb;75(2):105-12

- Phytomedicine. 2003 Mar;10(2-3):95-105.

- Phytomedicine. 2000 Oct;7(5):365-71

- Eksp Klin Farmakol. 2000 Jan-Feb;63(1):76-8

- Nord J Psychiatry. 2007;61(5):343-8

- Medicina (Kaunas). 2004;40(7):614-9

- J Altern Complement Med. 2008 Mar;14(2):175-80

- Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2009 Apr;19(2):186-9

- Chin J Physiol. 2009 Oct 31;52(5):316-24

- Am J Chin Med. 2009;37(3):557-72

- J Strength Cond Res. 2013 Mar;27(3):839-47

- Brain Behav Immun. 2014 Jul;39:204-10

- J Sports Med (Hindawi Publ Corp). 2014;2014:563043

- Front Nutr. 2015 Jul 31;2:24

- Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2018 Jan;43(1):63-70

- J Sports Sci. 2019 May;37(9):998-1003

- J Sport Health Sci. 2018 Oct;7(4):473-480

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.