You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Calcium & Metabolism

Unless you’re a cross-channel swimmer or sumo wrestler, it’s almost certainly true that you’ll perform better without excess body fat. Surplus fat acts as dead weight, increasing the load on your muscular system and demands on your oxygen transport system. So it’s hardly surprising that the search for an effective fat loss supplement is a Holy Grail of sports nutrition. Very few of the various potions and lotions on the market stand up to scientific scrutiny. But the real answer could be right under our noses in the form of one of the most familiar nutrients in our everyday diet, writes Andrew Hamilton.

Mention calcium and most people think of bones and teeth. But, while it’s true that 99% of the 1.2kg of calcium in the average human body goes to make up bone tissue (which itself acts as a ‘calcium reservoir’), the remaining 1% is vitally important. Calcium is needed to switch muscles on and off – without it no muscular contraction would be possible – and is also vital to the release of neurotransmitter chemicals, such as serotonin, acetylcholine and norepinephrine. Calcium is also an important co-factor for blood clotting and activates numerous enzyme systems in the body.

However, recent research has hinted at a more intriguing function of calcium in the body. Although it has long been known that all cells require calcium to function and that calcium also regulates the transport of other nutrients in and out of cells, there is growing evidence that calcium plays an important role in the regulation of energy metabolism and body composition and, in certain circumstances, may help reduce body fat and prevent weight gain.

The first indications that calcium might play a key role in metabolism came from two animal studies carried out in the late 1980s. In the first, two strains of rats prone to high blood pressure were placed on dietary regimes containing three different levels of calcium (2%, 1% or 0.1% by weight of the food consumed)(1). After 15 weeks, both strains of rats on the high calcium diets (2% and 1%) showed favourable improvements (ie reductions) in blood pressure. But the benefits didn’t stop there; rats on the high calcium diets also weighed less and had less body fat, with those on the 2% calcium diet showing the greatest changes. The second study found that increasing calcium in the diet from 0.1 to 2% led to reduced weight gain in both lean and fatty rats (2).

The first suggestion that this effect might apply to humans arose 12 years ago from a study of 11 obese African-American men, randomised into one of the following trial conditions:

a high-calcium intake, using supplementary yoghurt to raise calcium intakes to 1,000mg/day;

a yoghurt-free low calcium diet, containing only 500mg of calcium/day (3).

By the end of the intervention period, the men on the high-calcium diet had significantly lower body fat levels than those on the lower calcium intake. However, these results remained unpublished until recently because, at the time, scientists weren’t aware of a link between calcium intake and body composition and it was just assumed that these results were a ‘statistical blip’.

Initially, these early results stirred little interest within the scientific community, but a group of American scientists who had been studying the effects of calcium intake on bone mass in young women decided to investigate further and revisited the data from a two-year study published in 2001 (4), this time focusing on the link between calcium intake and body composition (5). The resultant data, collected from 54 women, were extremely intriguing. Although they observed no direct relationship between calcium intake and body fat levels, there was a very clear relationship between body fat and the calcium density of the diet.

The term ‘calcium density’ simply refers to how much calcium is consumed as a proportion of total calorie intake. For example, a diet containing 1,000mg of calcium per day and a total intake of 1,000kcal per day has a calcium density of 1mg per kcal. A diet containing 1,000mg of calcium and a total intake of 2,000kcal may have the same calcium content but has only half the calcium density. The results of this study showed that the density of the diet was inversely linked to changes in body weight and body fat – ie a high calcium density predicted weight loss and body fat reductions, and vice versa.

In order to further study the link between calcium, calorie intake and weight/fat changes, the scientists then split the women into two groups: those women who consumed more calories per day than the group average of 1,876kcal, and those consuming less. This produced two important findings:

In the high-calorie group, it was overall calorie intake rather than calcium intake that predicted changes in weight/fat mass;

However, in the low-calorie group, it was calcium intake rather than calories that predicted these changes, with a higher calcium intake producing more weight and fat loss! This effect was not small either, with calcium intakes of 1,000mg per day predicting a body fat loss of 2.6kg over two years compared with a gain of 1.8kg with calcium intakes of 500mg per day!

These results made nutritional scientists sit up and take notice and further investigations into calcium intake and body composition soon followed. In one of these studes, the dietary intakes of 53 children aged 2-5 were analysed in relation to body fat mass measured at 5 years, 10 months (6). A clear relationship between calcium and body fat was observed; the higher the dietary intake of calcium, the lower the body fat mass.

These results seemed to confirm those of a meta-analysis of five separate studies on calcium intake and body composition, involving a total of 780 women of all ages (7). In each of these studies, the calcium-to-protein ratio of the diet was inversely linked to either body mass index (BMI) or weight change – ie a high calcium-to-protein ratio predicted a lower BMI or weight loss, and vice versa. In fact, a difference of 1,000mg per day of calcium intake was associated with an average difference in body weight of 8kg!

The growing body of evidence in support of calcium as a modulator of body composition was given added weight by the ‘Quebec Study’ – another piece of research originally designed to assess the impact of calcium intake on bone mass (8). A total of 235 men and 235 women were split into three groups according to their average daily calcium intake, as follows:

Low – less than 600mg per day;

Medium – 600-1,000mg;

High – more than 1,000mg.

The researchers found that women in the low calcium group had significantly higher body weight, percentage body fat, total fat mass, BMI, waist circumference and total abdominal adipose (fatty) tissue than those in the other two groups. The same overall trend was observed for men, although the differences were less significant.

Yet another study originally designed to assess the impact of calcium intake on bone mass in young women examined the impact of calcium supplementation (9). In this three-year double blind study, 52 young women were split into two groups: a calcium group, supplemented with 1,500mg per day of calcium, and a control group on placebo. Analysis showed that women in the calcium group gained less fat over the study period than the controls, further supporting the relationship between calcium and body weight.

Humans require over 40 nutrients for health, of which calcium is just one. And because body composition is affected by numerous (often more significant) factors, such as activity levels and total calorie intake, discerning the individual effect of a single nutrient is fraught with difficulty. Hardly surprising, then, that some studies on the link between calcium and body composition have drawn a blank!

For example, a meta-analysis of nine trials on the effects of dairy produce supplementation on body weight/composition found no differences between supplemented and unsupplemented groups in seven of the trials, while the remaining two (carried out on older adults) actually demonstrated a weight gain in the supplemented groups (10)! However, these results need to be interpreted with caution since it was not clear how many extra calories the dairy supplemented groups were consuming as a result of consuming the extra dairy produce.

The same researchers then carried out a metaanalysis of calcium supplementation trials and body composition, remembering that supplements provide more calcium without extra calories. Of the 17 trials analysed, only one found greater weight loss in the supplemented group than the controls, while in the remaining studies, the changes in body weight and/or body fat were strikingly similar between groups.

Once again, caution is required when considering these results. For one thing, many of these studies were not specifically designed to investigate the link between calcium and body composition; for another, there is speculation that other compounds found in dairy products may act in concert with dietary calcium to produce weight loss effects, including whey proteins, conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) and branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs). These substances would not have been present at higher levels when just calcium supplements were given.

The importance of correct trial design when assessing the effectiveness of calcium supplementation and weight loss is illustrated by a study carried out last year on 100 obese women (11). All the subjects followed a weight-loss diet for 25 weeks, but one group received 1,000mg per day of supplementary calcium throughout this period, while the controls were given a placebo. Although the calcium-supplemented group lost more weight than the controls (7.0kg and 6.2kg respectively) and also lost more fat, the differences were deemed too small to be significant.

However, the study was not specifically designed to detect changes in body weight and fat mass between groups, and statisticians pointed out that as many as 500 subjects per group would have been required to reliably detect a difference of just 1kg. The researchers went on to suggest that had the study run for longer with more subjects, it might well have been possible to conclusively demonstrate a weight loss effect of calcium, even without other dairy components.

Another study carried out last year lent concrete support to the idea that calcium supplementation can help reduce fat (12). In this trial, 32 subjects were placed on a controlled calorie diet designed to promote weight loss on an individual basis by supplying each subject with 500kcal less per day than the amount calculated to keep them at a constant weight. The subjects were also randomly assigned to one of three groups:

Control – consuming 0–1 servings of dairy products per day while taking a 400–500mg calcium supplement and a placebo pill;

High-calcium – with the placebo replaced by 800mg per day calcium carbonate;

High-dairy – as group 1 and with the same total calorie intake (ie maintaining a 500kcal per day deficit) but consuming three servings of dairy products per day as part of the diet.

After 24 weeks, subjects in the control, high- calcium, and high-dairy groups lost 6.4%, 8.6%, and 10.9% of body weight respectively. Fat mass followed the same trend, with respective losses of 8.1%, 11.6%, and 14.1%. Intriguingly, fat loss from the abdominal region represented just 19% of total fat loss in subjects in the control (low-dairy) group but 50.1% and 66.2% for those in the high-calcium and high-dairy groups respectively. (Fat carried on the abdominal region is associated with a higher risk of illness, including coronary heart disease, so a greater fat loss from this region is significant.) These findings suggest that, while calcium seems to offer weight loss benefits, there may indeed be other co-factors in dairy produce which enhance this effect.

Implications for athletes

To date there have been no studies specifically considering the effect of high calcium diets on fat reduction in athletes. However, we can be cautiously optimistic that the same principles would apply; positive results have been obtained in studies on men and women, young and old, although the indications are that the effects may be more significant in women than men.

There is also evidence that any fat loss effect is stronger when an increased calcium intake is provided in the form of dairy produce rather than calcium supplements, possibly because of other nutrients present in milk products. But it’s important to realise that any fat loss effect provided by an increased calcium intake will be undermined by the fat gain effect of consuming surplus calories!

It’s also worth emphasising that the ‘scientific jury’ has yet to deliver its final verdict on this issue; as PP went to press, the results of a new large-scale one-year study on 155 young women were published, showing no differences in body weight change between low, medium and high dairy diets containing the same number of calories (13). This study doesn't negate the others, of course, but does indicate that more research will be needed before we can draw definitive conclusions.

The key, therefore, for those who want to go down this route, is to replace low-calcium foods with high-calcium foods (see table below) while maintaining roughly the same calorie intake. And since most calcium-rich foods are proteins, it makes sense to replace non-dairy proteins with dairy proteins, which will also ensure you maintain your intake of workout-fuelling carbohydrate.

HOW MUCH CALCIUM?

| Food | Portion size | Calcium content (milligrams)* |

|---|---|---|

| Cheddar cheese | 100g | 720 |

| Milk (all varieties) | Pint | 620 |

| Canned fish with bones (sardines, salmon, pilchards etc) | 100g | 550 |

| Sesame seeds | 100g | 420 |

| Watercress | 100g | 170 |

| Low-fat yoghurt (fruit) | 100g | 150 |

| Spinach | 100g | 136 |

| Fromage frais (plain) | 100g | 89 |

| Peas (frozen, cooked) | 100g | 59 |

| Wholemeal bread | 100g | 54 |

| Baked beans | 100g | 53 |

| Broccoli | 100g | 47 |

| Oranges | 100g | 40 |

| Iceberg lettuce | 100g | 20 |

| Wholemeal bread | 100g | 54 |

| White rice (boiled) | 100g | 18 |

| Lean beef | 100g | 15 |

| Avocado | 100g | 11 |

| Potatoes (boiled) | 100g | 5 |

| Apples (boiled) | 100g | 4 |

If you do decide to bump up your calcium intake, don’t go overboard. Although excess dietary calcium can be excreted quite easily, very high calcium intakes, combined with high vitamin D or low magnesium intakes, have been linked with soft tissue calcification, whereby excess calcium is dumped in body tissues, leading to joint problems and kidney stones.

The Food Standards Agency recommends a maximum level of calcium supplementation of 1,500mg per day, and it would seem wise not to exceed a combined food/supplement calcium intake of 2,000mg per day (14). Given that the recommended daily amount (RDA) for calcium is set at around 800mg per day for adults, and that most of the studies referred to above showed the greatest effects on weight loss at calcium intakes of 1,000mg per day or more, a sensible strategy might be to increase your intake of calcium-rich dairy produce by around 50% (to produce a food calcium intake of around 1,200mg per day) in the first instance!

WHAT’S GOING ON?

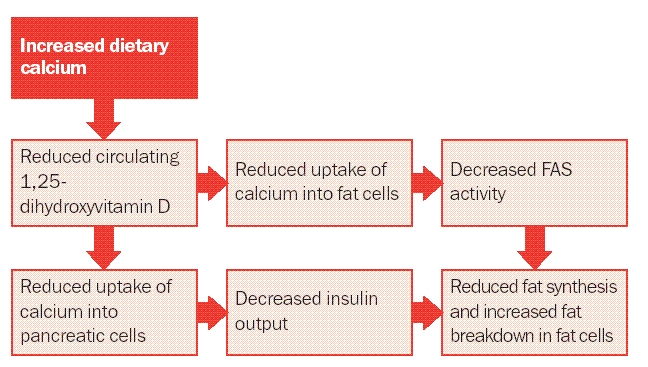

How is it that increasing calcium intake seems to exert a weight/fat loss effect? Vitamin D acts as both a vitamin and chemical messenger, and one of its jobs is to stimulate calcium uptake into the cells of the body when blood calcium levels are low. However, when blood calcium levels are high (for example on a high-calcium diet), levels of a particular metabolite of vitamin D (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D) fall, and this in turn reduces the rate at which calcium is transferred into cells, including fat cells and pancreatic cells.

A reduced calcium level in fat cells decreases the activity of a fat storage enzyme called fatty acid synthase (FAS), which in turn leads to reduced fat synthesis and subsequent storage. Reduced FAS activity also leads to increased lipolysis (the breakdown of fat for energy).

At the same time, reduced calcium concentrations in pancreatic cells lead to lower insulin output which, in turn, results in reduced fat synthesis and enhanced fat breakdown in fat cells.

In combination, these processes – expressed in graphic form in the flow chart (below) – would help reduce fat deposition into (and storage in) fatty tissue. However, further research is needed to confirm this effect.

Flow chart: the link between calcium and fat reduction

References

Am J Hypertens 1988 Jan; 1(1):58-60

FASEB J 1989, 3137:A265(abs.)

FASEB J 2000, 14:1132-1138

Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001, 33:873-880

J Nutr 2003 Jan; 133:249S-251S

Int J Obes 2001; 25:559-566

J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85:4635-4638

Am J Clin Nutr 2003; 77:1448–52

J Bone Miner Res 2001; 16:S219

J Nutr 2003; 133:245S-248S

J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89:632–7

Obes Res 2004; 12:582–90

Am J Clin Nutr 2005; 81:751-756

UK Food Standards Agency Expert Group on Vitamins and Minerals 2003 (www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/evm_calcium.pdf)

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.