You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Fluid, carbohydrate and immunity: what all women should know!

How does the menstrual cycle affect a woman’s responses to exercise? Andrew Hamilton looks at recent research suggesting that women need to take extra care of their health and hydration status at certain times of the month

Numerous studies have demonstrated that exercise is beneficial for fitness and health and (In the longer term at least), it also boosts immunity. The caveat however is that immediately after training (especially long or hard sessions), your immune system becomes temporarily depressed, increasing the risk of coughs, colds, sore throats and other upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs). One theory to explain this phenomenon is that the increase in the body’s core temperature produced by exercise temporarily interferes with the normal functioning of the body’s immune cells, increasing the risk of infection and illness. This has implications for women: due to hormonal changes, the body’s core temperature fluctuates during the menstrual cycle, which begs the question: are female athletes in training women more at risk of URTIs and other infections at certain times of the month?Carbohydrate and time of the month

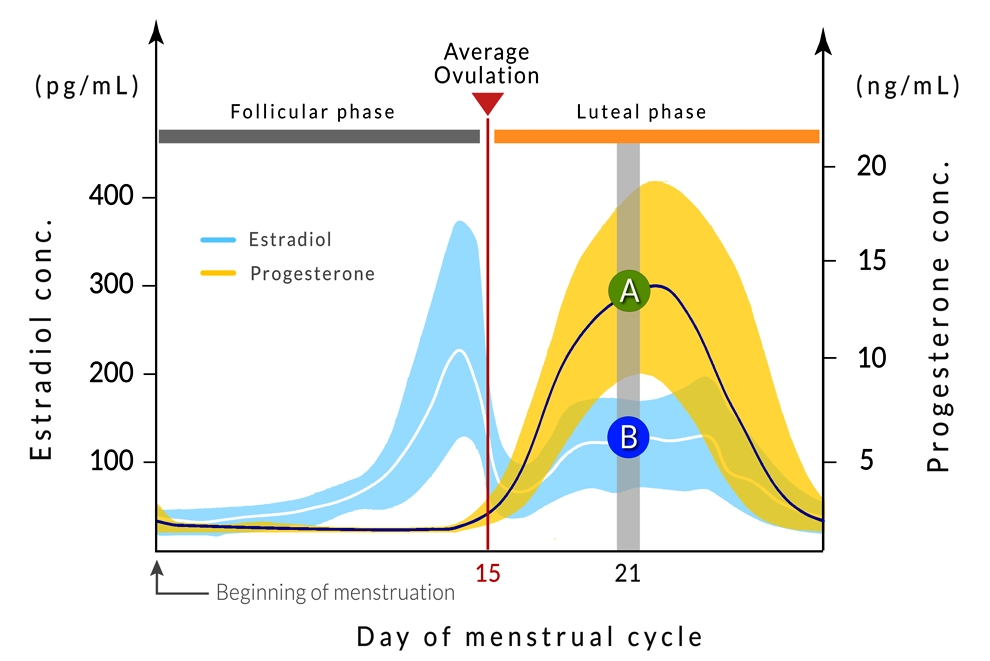

Although there’s been relatively little research into this topic, one study carried out by Japanese scientists makes for interesting reading. In this study, researchers monitored the immune responses in women who undertook cycling trials at different times in their menstrual cycle (no pun intended!)(1). These were the follicular phase (typically around 5-14 days after the start of menstruation) and the luteal phase (typically around 14-28 days after menstruation) – see figure 1 for an overview of these phases. They also investigated whether giving carbohydrate during exercise affected the immune responses in any way.Figure 1: Typical hormonal changes in women during the menstrual cycle

The blue band (shows the typical range of estradiol levels in the body through the cycle, with the white line indicating the average levels. The yellow band and blue line show the range and average levels respectively for progesterone. The pre-ovulation phase is known as the follicular phase (characterised by low progesterone/estradiol spike) while the post-ovulation phase is known as the luteal phase (characterised by high levels of progesterone).

Six healthy but untrained women completed four separate cycling trials. Each consisted of 90 minutes of cycling at 50% peak aerobic power (easy intensity) followed by a high intensity time-trial performance test, which lasted 10 minutes. The four trials were however conducted at two different points in the menstrual cycle and were as follows:

- Follicular phase consuming a carbohydrate drink

- Luteal phase consuming a carbohydrate drink

- Follicular phase consuming a carbohydrate-free (placebo) drink

- Luteal phase consuming a carbohydrate-free (placebo) drink

Luteal phase and immunity

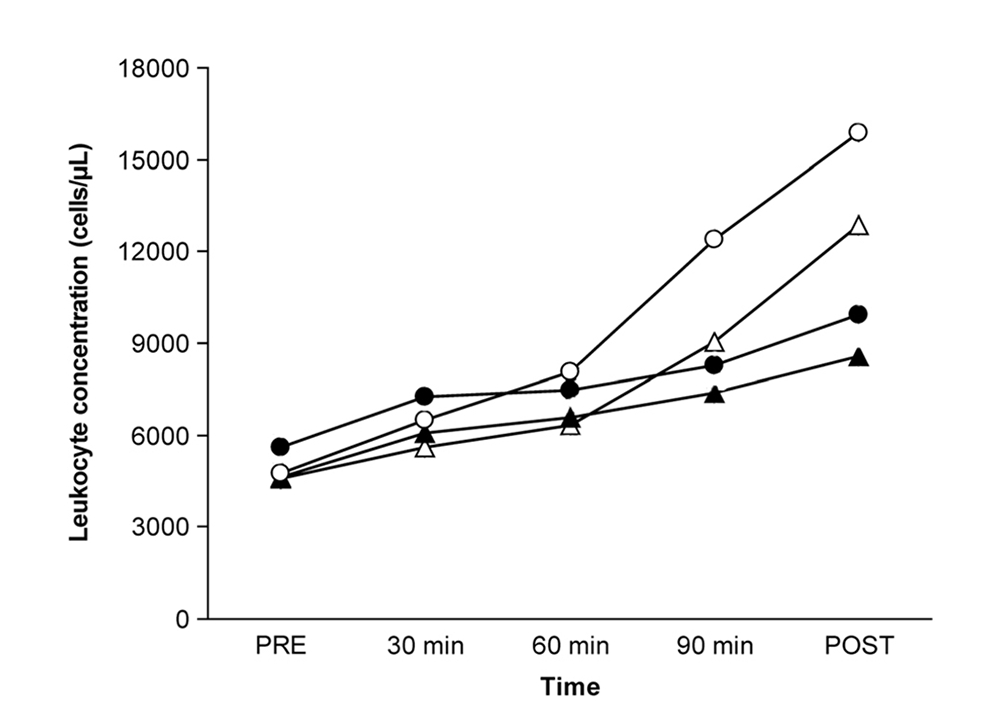

The first main finding was that when the women were in the luteal phase of their menstrual cycle, their core temperatures were higher both before and during exercise than when they were in the follicular phase. A second finding was that compared to the follicular phase, when the women were in the luteal phase of their cycle and drank the placebo beverage, the exercise trial resulted in a larger rise in immune cells called leucocytes – basically, a measure of how much stress the immune system is under (see figure 2). High post-exercise levels of blood leucocytes indicate compromised immunity and increased risk of an URTI. However, when the women had consumed the carbohydrate drink while performing the luteal phase trial, the rise in leucocytes was not nearly as great – ie consuming carbohydrate during exercise helped to reduce the amount of immune stress that resulted. In a nutshell, exercise during the luteal phase resulted in higher core temperatures and lower markers of immunity than the same exercise performed in the follicular phase. BUT, when carbohydrate was consumed during luteal phase exercise, immune function was hardly compromised at all.Figure 2: Immune stress after training

Circles = luteal phase; triangles = follicular phase. Solid circles/triangles = consuming carbohydrate; open circles/triangle = no carbohydrate.

The fluid connection

Another study carried out the following year by the same team of researchers looked at the effects of water-only ingestion on core temperature during exercise in the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle(2). Eight healthy young women with regular menstrual cycles performed cycling exercise in hot conditions for 90 minutes at 50% peak aerobic power during the low progesterone (follicular) phase and high progesterone (luteal) level phase, with or without water ingestion. In the water ingestion trials, the subjects ingested an amount of water that was equivalent to the loss in body weight occurring in the earlier non-ingestion trial. For all four trials, core temperature, cardiorespiratory responses, and ratings of perceived exertion were measured.The results of this study showed that, compared to the follicular phase, the women’s core temperatures in the luteal phase of the cycle averaged around 0.4C higher without water and 0.2C higher when consuming water. By contrast, in the follicular phase, consuming or not consuming water made no difference to core temperatures, which as stated above, were lower than in the luteal phase. Unlike the study above, the researchers in this study didn’t measure markers of immunity; extrapolating from the previous study (where the addition of carbohydrate helped ameliorate immune suppression), we probably wouldn’t have observed differences in a water-only trial. But what these results do suggest is that when exercising in hot conditions, women should take more care to keep properly hydrated when they’re in the luteal phase of their cycle (in order to keep core temperature increases to a minimum, which reduces perceived exertion and minimises any performance decrement(3)).

Practical advice for female athletes

Previous studies have already demonstrated the link between immune stress and exercise – for example there’s a substantial increase in leukocyte concentration during endurance exercise, and this increase depends on the intensity and duration of exercise(4). We also know from studies on male subjects that consuming carbohydrate during exercise suppresses the rise in leucocytes, thereby helping to prevent a post-exercise dip in immunity(5). These studies suggest that women exercising during the luteal phase may be especially at risk of a post-exercise immune dip, and that consuming carbohydrate during exercise can ameliorate this dip. They also suggest that warm-weather exercise in the luteal phase has a bigger impact on raising core temperatures, which can be detrimental for performance. Consuming water during exercise helps reduce this effect but doesn’t abolish it. Putting the two studies together, it’s reasonable to conclude that female athletes in the luteal phase of the cycle and who are training or competing in warm/hot weather should make consuming carbohydrate and fluid a priority during longer bouts of exercise. A very simple way to ensure this is to consume carbohydrate drinks, which tick both boxes!References

- J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2014 Aug 12;11:39

- J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2015 Jul 15. [Epub ahead of print]

- J Appl Physiol (1985) 1999; 86:1032-9

- Nutrients. 2012;4:1187–1212

- J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2002;12:145–156

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.