Marathon carbohydrates

Which works best before and during a marathon: carbs in liquid or solid form?

When I'm out on the lecture circuit, giving talks to runners preparing to run the marathon, I'm almost always hit with the same questions: how much carbohydrate do I need to take in during the race? Does it matter if the carbos are in liquid or solid form?The first question is easy to answer. To give their muscles a decent boost during the final, carbo-depleted miles of the race, marathoners need to take in more than 30 grams of carbs per hour DURING the race. The easiest way to accomplish that is to slurp down 12 ounces of standard sports drink just before the race begins and five to six swallows every 15 minutes thereafter.

I always finesse the second question, a necessary strategy since no scientific study has specifically compared the effects of liquid versus solid intakes on marathon performances. I point out that solids take longer to absorb than liquids, a bad deal in the marathon since you want to get carbs to your muscles quickly and relentlessly. Sports drinks are easy to buy or make, and their carbohydrate is quickly absorbed, so why not use them?

So what about 'gels'?

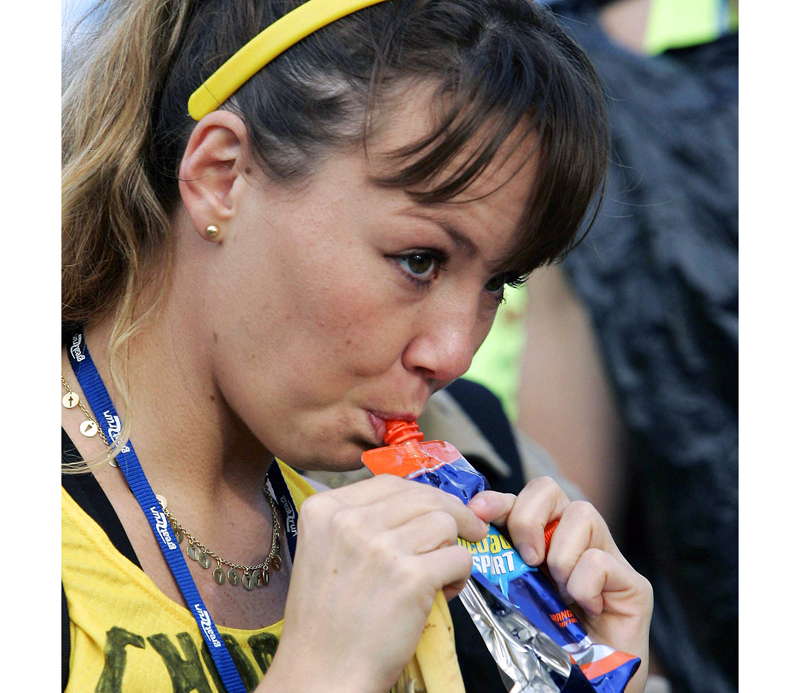

However, lately audiences have been taking a different tack. Anticipating my naysaying to cherry-pie and sweet biscuit intake during the race, more sophisticated runners have been asking if it's okay to use 'gels' during the marathon. The first few times I heard this question, I replied that shaving the body with gel was a great strategy for swimming, not marathoning, until someone finally informed me that energy gels were actually gooey carbo-hydrates in little packets with names like 'Pocket Rocket,' 'ReLode,' 'Squeezy,' and 'Gu.' Increasing numbers of marathoners have been squirting these goos into their mouths while racing. Many of them report that they 'feel great' shortly after gulping down these semi-solid products, and that they aren't troubled by the 'sloshing-around' feeling they get when they drink sports beverages. From their reports, it would seem that the gels are miracle products.

Of course, I'm a cautious, non-adventurous kind of chap. so I've tried to put the damper on runners' enthusiasm for these products, pointing out that if you dump a load of goo into your stomach along with a little liquid, it's hard to know what the actual CONCENTRATION of that carbohydrate will be. That concern is not an esoteric one: if the carbo concentration is too high (too much goo, not enough liquid), the carbohydrate will be absorbed slowly and may even pull fluid into your gut - lowering your blood volume and dehydrating you in the process. If the carbo levels are too low (too little goo, too much water), not enough carbs will get to your muscles, and you'll limp through the final miles of the marathon with sad, glycogen-depleted legs. The commercial sports drinks are formulated just right, I always say, so why not just use them and throw the goo in the bin - or use it as a balm to soothe your aching feet?

What the Dutch researchers found

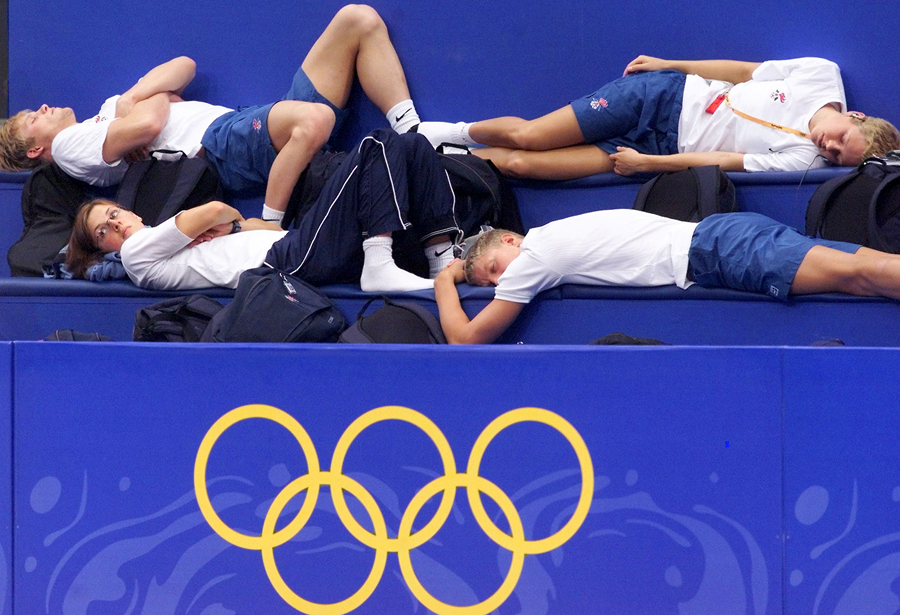

But does our final arbiter - scientific research - actually back me up? Recently, scientists at the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands conducted the very first study to compare the merits of liquid versus solid (and near-solid) carbohydrate intake before and during prolonged exercise. In the Utrecht study, 32 healthy male triathletes who were training for at least a one-fourth triathlon took part in gruelling exercise sessions. Each session consisted of two bouts of cycling lasting for 51 and 43 minutes, respectively, at an intensity of about 75% VO2max (85 per cent of maximal heart rate) and two running bouts lasting 43 minutes each, again at 75% VO2max. Pedal frequency during cycling was always kept between 80 to 90 rpm.

The workouts were planned to proceed as follows: after 51 minutes of cycling, a triathlete rested for eight minutes and then ran for 43 minutes. After a six-minute rest, the triathlete completed a maximal test on an exercise bike consisting of three minutes of pedalling at 175 Watts and then three minutes of 'all-out' performance. After four minutes of rest, the triathlete then cycled for 43 minutes, rested for six minutes, sizzled through a second maximal test on the bike, rested for four more minutes, ran 43 minutes, rested for six, and then completed a final supra-max biking test. It was tough! Total planned exercise time exceeded three hours, all of it with heart rates at or above 85 per cent of maximal. In reality, though, the triathletes didn't always make it through all three hours, often stopping after about two hours or so (during the second cycling episode or second run).

How did the solid and liquid carbohydrates fit in? All triathletes performed three of the rugged tests described above, each time with a different feeding regime. On one occasion, the triathletes consumed sports drinks throughout the trial (we'll call this the 'F' test, for fluids). On another, they ingested a mix of liquids and solids, consisting of orange juice diluted with an equal amount of water, white bread, marmalade, and bananas (we'll call this the 'S' treatment, for solids). During a third session, the triathletes sipped a liquid placebo containing nothing more than colouring, flavouring (citric acid), and xanthum gum for thickening (the 'P' group). Both the sports-drink and solid-food regimes provided the triathletes with about 100 grams of carbohydrate per hour, while the placebo supplied no carbohydrate at all. Actual water intake was about the same for the three groups.

An easy win for fluids

Which treatment - F, S or P - was actually best? Sixteen (out of the 32) triathletes were able to complete all three rugged hours of exercise when they took in fluids, but only nine could handle the strenuous affair with solids, compared to seven with placebo. Average total exercise time was 180 minutes for the F troop, 126 minutes for S subjects, and 120 minutes for P people. In other words, consumption of fluids rather than semi-solids was correlated with much stronger endurance performances.

Supra-maximal exercise capacity also tended to be higher with liquids, averaging about 371 Watts with fluid, 365 Watts with solid food, and 362 Watts with the placebo. Carbohydrate in fluid form was an all-around winner in terms of both aerobic and anaerobic performance.

A thumbs-down for fat

Right now there's a lot of talk in the lay press extolling the merits of higher fat intakes for endurance athletes. These articles and ads claim that fat is the key fuel for endurance performance and that athletes who want to perform better need to 'learn' to burn fat more efficiently during exercise (one of the ways to do this is supposedly to eat more fat). Well, guess what? The most efficient fat-burning occurred in the placebo group (no surprise since they were low on carbohydrate) - the group which performed the worst during the tests! The fluid people, who performed best, broke down considerably more carbohydrate and quite a bit less fat - which is exactly what you want if you hope to produce your highest-octane performances.

But that's a digression. What's the bottom line about carbo intake during the marathon? Well, no offence to the makers of 'energy gels', but there's no evidence that these products work better than standard sports drinks. In fact, the evidence leans toward the good-old fluids with dissolved carbohydrate. When you use a sports drink, you can be sure that the carbohydrate is ready to be absorbed with maximum quickness, and you can depend on the fact that the carbs are in the right concentration for you. During glycogen-depleting exercise, that's what you want!

What's best for the ultras

But what if you want to run something longer than a marathon? Perhaps the 54-mile Comrades Race in South Africa, a 100-mile competition, appeals to you, or even a five- to six-day leg pulverizer.

Since fat provides a major share of the energy required whenever a race lasts for five hours or more, you might think that the consumption of solid, fat-containing foods during the competition would keep you going. As we've mentioned before, the high amounts of energy needed during multi-day races, in which athletes often burn over 10,000 calories per day, reinforce the idea that fat is preferable, because - although carbohydrates COULD provide such grandiose quantities of fuel - the actual amount of eating involved would be rather formidable. To take in 10,000 calories of carbohydrate, for example, you'd need to eat about 142 slices of bread each day, or a piece every 10 minutes! Since fatty foods are more calorie-dense, they at least give your jaws a bit of a breather.

Most ultra-runners seem to like this idea and gulp down generous amounts of cakes, biscuits, and chocolate bars as they cruise along. Unfortunately, there are a couple of problems with the idea of munching fat. First of all, to burn fat during exercise you don't really need to EAT fat; you could simply rely on the lard already tucked away in your tummy and thighs. The other problem is that if you focus primarily on fat consumption, you may not take in enough carbohydrate to keep your leg muscles happy. If your leg muscles run too low on carbohydrate, you won't be able to run at anything faster than a slow stumble, even if a major proportion of the world's fat supply is floating along in your bloodstream.

The bottom line?

So here are the optimal energy-intake patterns for races of different durations:

1. If the race is 60 minutes or less, consuming either carbohydrate or fat during the competition is pointless; plain water is fine

2. If the race lasts for 60-200 minutes, take five to six swallows of a 6-8 per cent carbohydrate sports DRINK every 15 minutes during the race. That's all you need!

3. If the race lasts from 200-360 minutes, utilise a 6-8 per cent carbohydrate, 4-per cent 'medium-chain triglyceride' (MCT) sports drink throughout the race, again taking in five to six swallows every 15 minutes. The MCTs (obtained in most health-food shops) are absorbed more quickly and metabolised more efficiently than 'normal' fats. To make sure you have the right concentration, add 40 grams of MCTs to each litre of your sports drink. Recent scientific studies suggest that MCTs may improve endurance during races lasting longer than three to three and one-half hours or so,

4. For events lasting more than six hours, follow strategy No. 3, but also wolf down some solid foods which contain rich lodes of carbohydrate. The presence of fat in these foods won't hurt you and may help you keep close to energy balance; chocolate bars, cakes, and pies, along with the standard fare of fruit, soup, and sandwiches, are all acceptable possibilities. Experiment with various comestibles before your race to make sure that you'll be ingesting something which your digestive system tolerates easily.

('Exercise Performance as a Function of Semi-Solid and Liquid Carbohydrate Feedings during Prolonged Exercise,' International Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 16(2), pp. 105-113, 1995)

Owen Anderson

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.