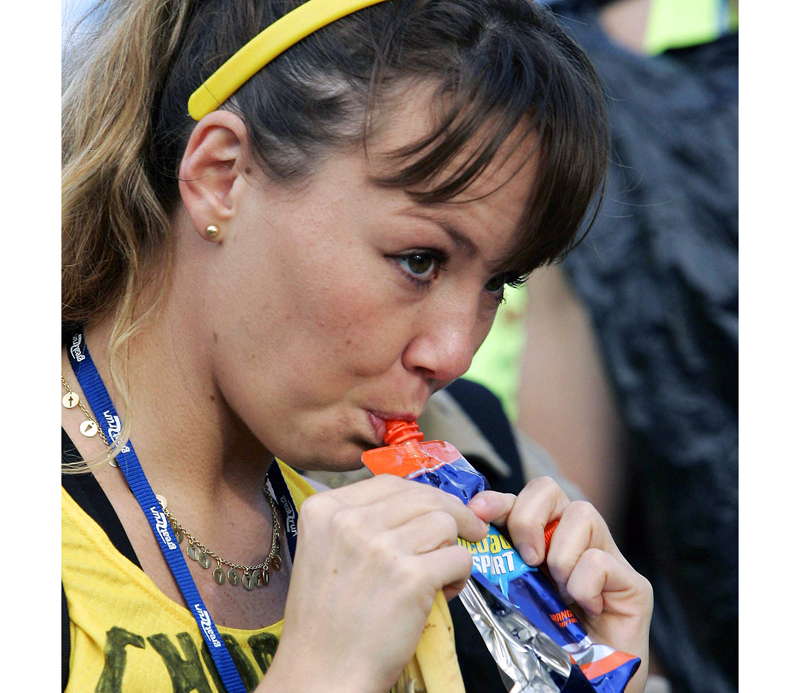

Recovery nutrition: starting on the move!

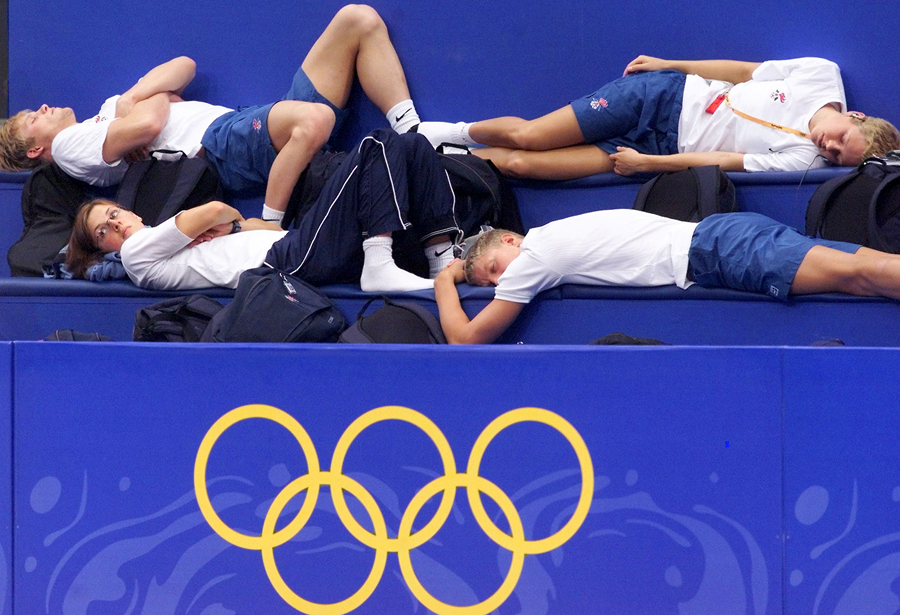

For serious endurance athletes in regular training, it cannot be overstated how important recovery is following exercise. All other things being equal, athletes who recover faster and more fully can train or compete again sooner and perform better. Assuming you’re getting adequate physical rest following a training session or competition, the next single most important thing you can do to boost performance is to improve your recovery nutrition. In broad-brush terms, there are four major nutritional requirements for rapid recovery after long and/or strenuous exercise: carbohydrate, protein, fluid (water) and electrolyte minerals. Of these nutritional requirements, carbohydrate is by far the most researched, and over recent years, much has been written about the benefits of consuming carbohydrate following exercise.

The fundamental importance of carbohydrate

It was almost a century ago, when researchers first demonstrated that fatigue occurs earlier when subjects consume a low-carbohydrate diet (as compared with a high-carbohydrate diet) in the days preceding an exercise(1). This early research provided the initial evidence that carbohydrate was an important fuel source for sustaining exercise performance. However, it wasn’t until the development of muscle biopsy techniques in the late 1960s that sports science researchers were able to fully grasp the fundamental importance of carbohydrate for endurance exercise performance. In a series of studies by Scandinavian researchers, scientists discovered three key principles, upon which our current-day understanding is built upon(2-5). These key principles are as follows:

I. Muscle glycogen (stored muscle carbohydrate – the body’s 5-star fuel for high-intensity exercise performance) is depleted during exercise in an intensity dependent manner (see figure 1).

II. High-carbohydrate diets increase muscle glycogen storage and subsequently improve exercise capacity.

III. Depleting muscle glycogen with prior exercise then consuming a high-carbohydrate diet can boost muscle glycogen storage above and beyond normal storage levels.

Figure 1: Exercise intensity and glycogen depletion*

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.