You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Vegetarian athletes: accentuate the positive, eliminate the negative!

How do vegetarian and vegan diets stack up in terms of athletic performance? SPB looks at the evidence and provides guidelines for their optimization

There are several reasons why people turn to vegetarianism but the three most common are health, animal welfare and environment. The health concerns include the intensive farming of animals and the use antibiotics, growth hormones etc, residues of which can end up in the animal produce we eat(1). There’s also the fact that high meat (particularly red/processed meat) diets are associated with increased risks of coronary heart disease(2) and cancer(3). In addition, there are persuasive environmental arguments; it’s less efficient to feed people animals fed on grains and crops, and much more efficient feed people on the grains and crops directly. And then of course, there are all the concerns about animal welfare.What is a vegetarian diet?

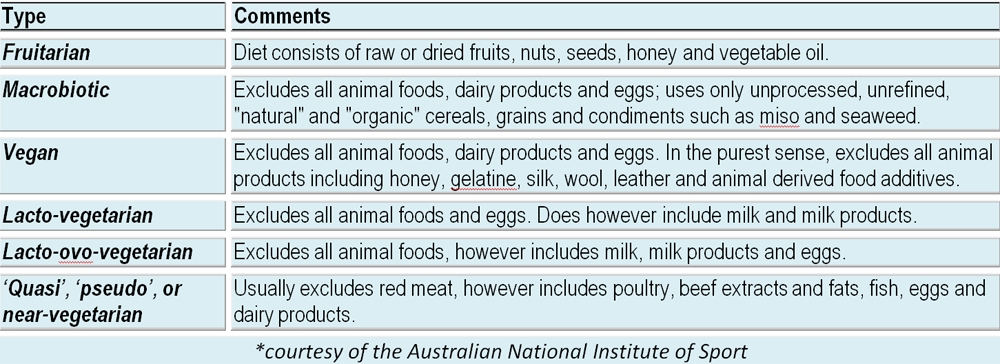

Before we go on to discuss the pros and cons of vegetarian diets for athletes, let’s clarify what vegetarianism actually means as there are a few different categories as shown in table 1 below. In this article, we’ll focus on lacto, lacto-ovo and macrobiotic/vegan vegetarian diets as a fruitarian diet is in reality simply too restrictive and nutritionally incomplete for an athlete in training.Table 1: Categories of vegetarian diets*

Vegetarian dietary benefits

In a comprehensive review of the evidence, the American Dietary Association concluded that a well-planned vegetarian diet is appropriate for individuals during all stages of the life cycle, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, and adolescence, and importantly, for athletes too(4).Looking at composition, the evidence suggests that vegetarian diets are usually rich in carbohydrates, essential fatty acids (omega-3 and omega-6), dietary fibre, and nutrients such as carotenoids (vitamin A), folic acid (an important B-vitamin), vitamin C, vitamin E and the mineral magnesium(5). Vegan diets however may struggle to provide enough vitamin B12 and calcium (because milk and milk produce is an excellent source of calcium)(5).

In terms of health and lifestyle benefits, a properly planned vegetarian diet can be ideally suited to athletes in hard training. For example, studies have shown that a vegetarian diet is associated with a lower risk of death from heart disease, lower blood cholesterol, lower blood pressure, and a lower risk of diabetes(4). Performance-wise, there are a number of potential advantages of a good vegetarian diet, the key ones being summarized in box 1 below.

Box 1: Potential performance benefits of a vegetarian diet

Although vegetarian diets have sometimes been regarded as ‘inadequate’ for competitive athletes, in some ways they are ideally suited: A few examples include:- High carbohydrate content – because of their higher reliance on cereals, grains and pulses such as lentils and beans, vegetarian diets are typically rich in carbohydrate, which is ideal for fueling training sessions and aiding rapid recovery. This is especially relevant because plentiful dietary carbohydrate intake is vital for all athletes, and inadequate carbohydrate intake is surprisingly common, even among elite athletes(6,7)!

- Antioxidants – vegetarian diets tend to contain higher levels of fruits, vegetables nuts and seeds, which means significantly higher intakes of antioxidants. There’s growing evidence that naturally-occurring antioxidants in these foods can reduce exercise induced muscle damage, attenuate post-exercise soreness and speed recovery(8,9).

- High magnesium content – magnesium is a crucial mineral for athletes because it’s pivotal to the process of energy production in the body and even mild shortfalls can impair performance(10). To make matters worse, a number of studies have shown that magnesium intakes in a variety of sportsmen and women are frequently inadequate(11). Good vegetarian diets on the other hand are likely to be rich in magnesium.

Are there performance benefits?

One of the perennial questions about vegan/vegetarian diets is whether they can produce performance benefits. In a 2016 comprehensive review study on this topic, researchers examined the evidence for the relationship between consuming a predominately vegetarian-based diet and improved physical performance(12). To do this, a systematic literature review was performed using the keywords vegetarian OR vegan AND sport OR athlete OR training OR performance OR endurance. The included studies:- Directly compared a vegetarian-based diet to an omnivorous/mixed diet

- Directly assessed physical performance, not biomarkers of physical performance

- Did not use supplementation

Another study published last year however argued that a vegan or vegetarian diet could possesses potentially advantageous properties for endurance performance(13). In this study, researchers reviewed the data and concluded that vegan/vegetarian diets being richer in fiber typically contain significantly more fiber than omnivore diets(14). In a healthy gut, an increased level of fiber results in a greater synthesis of short-chain fatty acids, and these short-chain fats could confer a benefit; short chain fats are thought to increase the activation of two key endurance signalling molecules - AMPK and PGC1-alpha.

Following a bout of endurance exercise, AMPK and PGC1-alpha are involved in the adaptation process, stimulating genes to synthesis more mitochondria and enzymes involved in endurance metabolism(15). So over time, this kind of dietary regime could in theory help athletes to improve the efficiency of aerobic metabolism, particularly fat oxidation. However, as alluded to above, robust data showing an endurance performance benefit (or disadvantage) to vegan/vegetarian diets is still lacking. Much longer-term studies will be needed to see if the benefits suggested above do indeed occur.

Caveats

Despite the potential benefits of a vegetarian/vegan diet, there are however important caveats to add here. The first is that all-important phrase used by the American Dietary Association – ‘well-planned’. Simply adopting a ‘non meat-eating’ strategy while keeping all your other dietary habits the same is unlikely to meet your nutritional needs. and may actually be detrimental to performance (see later). You need to think about and plan your diet, and not be lulled into a false sense of security that a meat-free diet will automatically provide benefits.For example, vegetarian athletes need to ensure that the carbohydrate they consume is of the whole unprocessed variety (eg whole grain bread and pasta, whole brown rice, whole grain breakfast cereals etc). Consuming whole carbohydrates will provide a much higher intake of the minerals zinc (important for protein metabolism in the body), iron (required for blood cell production and energy), as well as essential fats (needed for health and immunity). A vegetarian diet, high in white, refined carbohydrates, will likely struggle to meet these needs.

Another caveat concerns vegan diets. Because they are more restrictive (no eggs, milk or dairy produce) even well planned diets may struggle to meet the requirements for vitamins D and B12, and those of the mineral calcium. Iodine and selenium can also be a problem(16,17) since seafood is a major source of both these minerals and likewise with zinc(18), because the best sources of this important mineral tend to be animal proteins.

Iron is another potential concern for all vegetarians, but especially for vegans and macrobiotic dieters because vegetable sources of iron are much harder to absorb than animal sources (haeme iron – see this article). The problem is that even a mild shortfall of iron appears to not only reduce maximum oxygen uptake capacity and aerobic efficiency, but also to reduce the body’s training response to aerobic training(19). Moreover, research indicates that you can actually be quite iron deficient in the tissues without being diagnosed as iron anaemic by conventional blood tests(20). Young female vegetarian runners should take special care with iron since the monthly blood losses during menstruation combined with the pounding action of running (which breaks down red blood cells) makes them particularly vulnerable(21). Box 2 gives some useful tips increasing dietary iron intake (also applicable to non-vegetarians).

Box 2: Tips for increasing dietary iron intake

- Try and include more beans (especially lima beans), lentils, dark green leafy vegetables as well as eggs and nuts in your diet.

- Increase your intake of vitamin C-rich foods such as citrus fruits, berries, new potatoes, broccoli, sprouts, tomatoes, peppers, kiwis etc. Vitamin C helps make iron much more absorbable

- Don’t drink tea and coffee with meals as the tannins present strongly bind any iron present making it less available to the body.

- Pure bran is very high in phytates, which bind iron. If you want more fibre, don’t use bran products; get it by eating whole grain breads and cereals in the first place.

- Cook using stainless steel cookware, which can add useful amounts of iron to cooked foods.

Drawbacks

Are there any absolute drawbacks that vegetarian athletes face compared to their meat-eating rivals? In other words, does meat confer any special nutritional advantages that can’t be made good by careful selection of non-meat foods? One area where vegetarian diets will fall short is creatine content (see box 3).Box 3: Creatine and vegetarians

Creatine is a naturally occurring compound stored in muscle tissue (hence it is found in meat but not plant foods). Numerous studies have shown that creatine supplementation can enhance perform during short, very high-intensity bursts of exercise such as sprinting or resistance training and that the benefits are especially apparent when initial creatine stores in the muscles are low. Although creatine can be produced by the body from amino acids present in other protein foods of vegetable origin consumed, a number of studies have shown that vegetarians have lower total creatine and lower muscle creatine stores than non-vegetarians(22).In theory, the performance benefits of creatine supplementation in vegetarians with low creatine muscle stores should be more pronounced than in athletes who eat meat. Although there’s no conclusive evidence to confirm this, there’s some anecdotal evidence that athletes who have experimented with a vegetarian diet report that they don’t feel quite as ‘strong’ compared to a meat eating diet. For vegetarian endurance athletes, the lack of dietary creatine may not be an issue. However, strength, power and sprint athletes on a vegetarian diet may wish to consider some creatine supplementation.

Another potential drawback concerns protein because the diets of vegetarians generally provide significantly less protein than those of non-vegetarians(23). While this is not always a problem (as many athletes consume above the recommended protein intakes), vegetarians should still exercise caution as (unlike animal proteins) plant proteins tend to be limiting in one or more of the essential amino acids. This is a particular issue for vegans, who excluse all animal proteins such as milk, cheese and eggs.

It’s important therefore to combine different types of plant foods through the day so that low levels of essential amino acids in one food are complemented by high levels of amino acids in the other – eg combining legumes (beans and peas) and grains or legumes and nuts/seeds. The use of nuts and seeds deserves a special mention because these foods are not only the richest source of protein for vegans, they’re also excellent sources of zinc, which is often lacking in vegetarian diets, and especially so among vegans(24).

References

- World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2002;911:i-vi, 1-66, back cover

- 2010 Jun 1;121(21):2271-83. Epub 2010 May 17

- Cancer Res. 2010 Mar 15;70(6):2406-14

- J Am Diet Assoc. 2009 Jul;109(7):1266-82

- Proc Nutr Soc. 2006 Feb;65(1):35-41

- Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2004 Aug;14(4):389-405

- Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2004 Dec;14(6):684-97

- J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2010 May 7;7(1):17

- Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2005 Feb;15(1):48-58

- J Nutr 132:930-935 (2002)

- J Am Diet Assoc;86: 251–3 (1986) and Nutr Res;7:27–34 (1987)

- Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2016 Jun;26(3):212-20

- 2021 Nov; 13(11): 3884

- Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013;113:1610–1619

- J. Clin. Nutr. 2011;93:884S–890S

- 2004 Sep;20(9):738-46

- J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2003 Jan;16(1):111-3

- J Am Diet Assoc. 1980 Dec;77(6):655-61

- Am J Clin Nutr, 75(4): 734-42, 2002

- Med Sci Sports Exerc, 25(5): 562-71, 1993

- Med Sci Sports Exerc, 34(5): 869-75, 2002

- Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2004 Oct;14(5):517-31

- Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994 Aug;48(8):538-46

- Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2003 Jul 5;147(27):1308-13

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.