You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Hitting the bottle: what all coaches should know about supplement safety

Up to 80% of sportsmen and women regularly use dietary supplements to enhance sport performance. While the vast majority of these products are safe and legal, there’s worrying evidence that some are not. Andrew Hamilton investigates and provides guidelines for coaches with athletes in their care

Once upon a time, the use of ‘supplements’ to enhance sport performance was quite a rare phenomenon, and many products that were used were of dubious legality. However, our mushrooming understanding of exercise physiology combined with increasingly advanced manufacturing techniques has produced an explosion in the range and affordability of nutrient and herbal based sports supplements. Add in the ease with which knowledge can now be disseminated via the Internet and other social networks and it’s easy to see why sports supplement use has grown so dramatically.Supplementation culture

In 2019, the culture of ‘supplementation’ is widely accepted as the norm - not only among professional - athletes, but also among many recreational athletes and general fitness enthusiasts. Studies have shown that the routine use of supplements in athletes across a wide range of sports ranges from 40-88%(1) and that regular supplement use is now becoming increasingly common among young adolescent athletes(2).The most commonly used sports supplements include scientifically proven and safe substances such as carbohydrate energy drinks, hydration drinks and carbohydrate-protein recovery drinks. However, these kinds of supplements represent only the tip of the iceberg in terms of what is available. Ergogenic aids such as creatine monohydrate (to promote power/sprint performance) and caffeine (to enhance endurance performance) are also extremely popular. Although these need to be taken in larger doses (particularly creatine) than would be found naturally in the diet, the large amount of data accumulated in numerous scientific studies over the years indicates that as well as being effective, these supplements are by and large extremely safe for the vast majority of the those consuming them(3).

However, in addition to these more mainstream sports supplements, a growing consumption of natural (plant-derived) products has been registered over the last years. It is estimated that more than 1400 herbs have been commercialised for medicinal uses worldwide, with these supplements representing a multi-billion-dollar business(4). In the arena of sport performance, these products are usually marketed as performance enhancing aids, being presented as ‘legal and free of side effects’, helped by the commonly held misconception that ‘natural’ corresponds to not harmful. However, the publicised effects of these products and the recommended dosages are often based on scant and inadequate scientific evidence, which is causing increasing concern within the scientific community(5).

There’s also concern that while many herbal and non-herbal sports supplements may be safe when used individually as directed by the manufacturers, certain supplement combinations or inappropriate doses may not be. The liver is the main ‘detoxifying’ organ of the body and it is liver function that is likely to be initially compromised when problems occur. Given the sharp rise in the popularity of dietary supplementation among sports and fitness enthusiasts, it’s perhaps not surprising that during the last decade, there’s been a steep rise in the incidence of hepatotoxicity resulting from the use of dietary energy supplements or herbal formulations(6). These cases have ranged from mildly abnormal liver function tests with little or no adverse symptoms to full blown hepatitis resulting in liver failure and death(6).

Hormonal concerns

Even where there’s no evidence of acute or chronic changes to organ status (eg liver function), the use of certain types of supplements may produce undesirable effects within the body. In a key study by scientists from the University of Rome, researchers looked at the effects of consuming plant-derived supplements in recreational athletes(4). Twenty-three trained subjects who habitually used natural dietary supplements and 30 matched controls were analysed for their plasma biochemical markers and hormonal profiles.The laboratory tests revealed that there was no sign of any organ toxicity or damage in both the athletes and the controls. Rather alarmingly however, the hormone profiles revealed marked alterations in 15 (65%) out of the 23 of investigated athletes. Specifically, ten of the male athletes presented increased plasma levels of progesterone (see figure 1) while 15 subjects presented with abnormal oestrogen levels (figure 2), including five (2 females and 3 males) who had “dramatically” increased oestrogen values and a further two males with increased oestrogen levels, increased testosterone levels and associated suppression of luteinising hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone

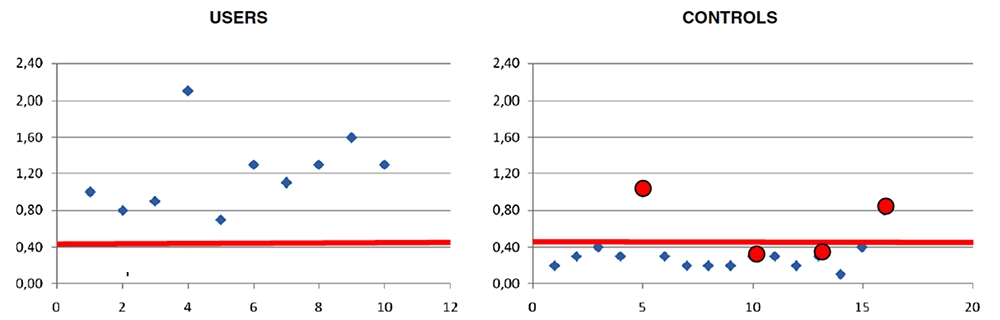

Figure 1: Values of plasma progesterone in 10 users of plant-derived supplements(4)

NB: 0.4 ng/ml (red line) represents the upper limit of the reference range in males. Female subjects are indicated with red circles. The x axis represents the subject identification number and the y axis represents the values of plasma progesterone. The plant-derived supplements consumed by these users included beta-Sitosterol, Pygeum extract, Guarana extract, Cordyceps extract, Rhaponticum Carthamoides, Muira Puama, Gotu Kola extracts and high doses of soy derived proteins.

Figure 2: Specific values of plasma estrogens in 15 users of plant-derived supplements(4)

NB: 35 pg/ml represents the upper limit of the reference range in males (green lines), 650 pg/ml represents the upper limit of the reference range in females (red line). The x axis represents the subject identification number and the y axis represents the values of plasma estrogens. In the users (left) there were 13 males and 2 females (red circles).

The researchers concluded that the habitual consumption of plant-derived nutritional supplements is frequently associated with significant hormonal alterations both in males and females. More worryingly, they also concluded that while these biochemical alterations were not associated with signs or symptoms of organ toxicity at the time of the study, it couldn’t be ruled out that in the mid-long term, these subjects wouldn’t suffer health problems arising as a consequence of chronic exposure to heavily altered hormonal levels.

Does familiarity breed contempt?

While it’s true that much of the recent concern over sports supplement safety has focussed on plant-derived (herbal) supplements that have been poorly researched for safety and efficacy, this doesn’t mean that other more commonly used and familiar supplements can always be used with impunity. A quick scan of the medical literature reveals that there are a number of cases of toxicity associated with health and sports supplements that might not be described as exotic.For example, a 2007 paper looked at the association between consumption of Herbalife nutritional supplements (not normally regarded as exotic) and acute liver toxicity(7). Following the identification of four cases of acute hepatitis associated with Herbalife intake in 2004, the Israeli Ministry of Health began an investigation in all Israeli hospitals. As a result, twelve patients with acute idiopathic liver injury in association with consumption of Herbalife products were investigated. Eleven of the patients were females (average age 49) and the average duration of Herbalife product consumption recorded in these patients was just under a year. The researchers noted that the hepatitis resolved in eleven patients, while one patient succumbed to complications following liver transplantation. However, three patients resumed their consumption of Herbalife products following normalisation of liver enzymes, which then resulted in a second bout of hepatitis!

Another case in point is vitamin D. Vitamin D toxicity as a result of supplementation has only been rarely reported in the past. However, in recent years, it has been reported much more frequently(8). This rise may be attributable to an increase in vitamin D supplement use among athletes and the general population alike, because of a growing realisation of the importance of optimum vitamin D intake for long-term health.

Although the normal concentrations of blood vitamin D blood span a wide range (see table 1), excessive and prolonged intake of vitamin D supplements can result on overload, leading to symptoms such as vomiting, loss of appetite, weight loss, thirst, excessive water intake and constipation. Current guidelines suggest that administration of vitamin D is safe at 1000 IU/day for ages 0-1, 2500 IU/day for ages 1-3, 3000 IU/day for ages 3-8, and 4000 IU/day for age 9 and above, adults and pregnant women(9). However, vitamin D supplements providing in excess of 5000IU per capsule are now fairly commonplace and it’s easy to understand how prolonged over-enthusiastic supplementation could lead to toxicity, especially as some individuals seem to be more vulnerable to vitamin D toxicity(10). In addition, the scientific literature reports at least one instance where a subject presented with life-threatening complications due to the intake of vitamin D-concentrated supplements, which turned out to contain 100-1,000 times the dose stated on the label of the dietary supplements(11).

Table I. Clinical Definitions of Vitamin D Levels(12)

| Vitamin D status | Blood concentration (nmol/L) | Blood concentration (ng/ml) |

| Severe deficiency | 12.5 | 5 |

| Deficiency | 37.5 | 15 |

| Insufficiency | 37.5 - 50 | 15-20 |

| Normal | 50-250 | 20-80 |

| Excess | 250 | 100 |

| Intoxication | 375 | 150 |

Another nutrient that has caused problems in the past is selenium. Selenium is an essential trace element, but can be toxic in excess. In May 2008, US FDA reported 201 individuals with adverse reactions to liquid nutritional supplements containing excess selenium resulting in the largest epidemic of selenium toxicity in the history of the United States(13). A retrospective observational case series was performed on nine patients between March 2008 and May 2008 with symptoms of selenium toxicity after consuming a nutritional supplement; testing on this supplement subsequently revealed almost 200 times the declared amount of selenium! However, even without errors in the formulation of supplements, optimum selenium supplementation can be tricky. Current recommendations are that adults should consume at least 55mcgs of selenium per day(14). However, many academics believe that optimum intakes may be in the range of 100-200mcg/day yet the upper tolerable limit is set at 400mcg per day – ie there exists a relatively small margin for error.

Yohimbe: A classic case of herbal hazard

Yohimbine is the principal alkaloid of the bark of the West African evergreen Pausinystalia yohimbe. There are 31 other yohimbane alkaloids found in Yohimbe. In Africa, Yohimbe has traditionally been used as an aphrodisiac, while in the West, Yohimbe has been used as both an over-the-counter dietary supplement in herbal extract form and prescription medicine in pure form for the treatment of sexual dysfunction. However, in recent years, Yohimbe has also become popular as an ingredient in ‘performance’ and ‘fat loss’ supplements.The problem with Yohimbe is that its consumption at higher doses can produce a number of side effects. These commonly include rapid heart rate, high blood pressure, overstimulation, insomnia and/or sleeplessness. Rarer side effects include panic attacks, hallucinations, headaches, dizziness, and skin flushing and more seriously, seizures and renal failure. Yohimbe in combination with drugs that inhibit the reuptake of norepinephrine, such as dextromethorphan, tramadol, some antidepressants, and central nervous system stimulants used to treat ADHD, can cause a ‘hypertensive crisis’. This is because such a combination leads to too much norepinephrine in the brain, which causes blood pressure to spike to dangerous levels; for this reason, Yohimbe should not be consumed by anyone with liver, kidney, heart disease, or a psychological disorder.

In a 2010 study, Californian researchers carried out a retrospective study into adverse drug events reported to the California Poisons Control Centre (CPCS) associated with Yohimbe-containing products within a 7-year period (2000-2006)(15). A total of 238 cases were identified and the prevalence (per 10,000 total adult exposures) increased from 1.8 cases in 2000 to 8.0 cases in 2006. The majority (98.7%) of cases involved herbal Yohimbie products and the most common adverse reactions included: gastrointestinal distress (46%), tachycardia (43%), anxiety/agitation (33%), and hypertension (25%). The researchers concluded that there was a substantial increase in the prevalence of adverse reaction to Yohimbe herbal products and that these reactions were associated with significantly more serious outcomes than the average exposures reported to the CPCS.

Summary and conclusions

Sports supplementation is now a routine and accepted practice among many sportsmen and women at all levels of sport. The good news is that the most commonly used sports supplements such as carbohydrate energy drinks, hydration drinks and carbohydrate-protein recovery drinks are both scientifically proven and safe. However, many athletes use a range of other supplement products, including vitamin/minerals, creatine, caffeine, amino acids and numerous biologically active substances derived from plant products; far fewer of these are scientifically validated and many may have unexpected and/or undesirable side effects.Specifically, the evidence suggests that the use of herbal products may be particularly problematical for athletes’ health and well-being (not to mention the legality of some products). There’s even evidence that fairly routine supplements may pose problems if administered haphazardly or are dubiously sourced. Those with athletes in their care should be aware of these issues and encourage their athletes to approach the issue of supplementation cautiously and scientifically, not forgetting that top sports performance starts with optimum training and a top quality day-to-day diet!

Practical recommendations

Here are some practical recommendations for coaches and other sports professionals who have athletes in their care:- *Try to foster a culture of the importance of diet for performance rather than sports supplements;

- *Consider running educational programmes for your athletes so that they can understand which kinds of nutritional products are likely to be safe and effective and which are not;

- *Keep a record of any products your athletes use and check the listed ingredients for potentially harmful ingredients;

- *Familiarise yourself with the current WADA guideline on prohibited substances to make sure that your athletes don’t inadvertently fall foul of doping regulations;

- *As a rule of thumb, products supplied by larger, well-established companies with manufacturing procedures accredited to recognised standards are less likely to suffer problems such as cross contamination or incorrect formulations (check ‘Informed Sport’ for more info: informedsport.com);

- *Discourage your athletes from using herbal products of any description; these are far more likely to be problematical.

- Nutr Hosp 2009, 24:128–134

- Br J Sports Med 2005, 39:645–649.

- Amino Acids. 2011 May;40(5):1369-83

- J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2012, 9:28

- J Sports Sci Med 2008, 7:562–564

- Ann Intern Med 2002; 136: 590-595

- J Hepatol. 2007 Oct;47(4):514-20

- Turk J Pediatrics 2012; 54: 93-98

- J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: 53-58

- J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2010; 121: 71-77

- Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2010 Jun;48(5):460-2

- Pediatrics 2008; 122: 398-417

- Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2012 Jan;50(1):57-64. Epub 2011 Dec 14.

- US Office for Dietary Supplements2012; ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Selenium-HealthProfessional

- Ann Pharmacother. 2010 Jun;44(6):1022-9. Epub 2010 May 4.

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.