You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Hooked on caffeine: the true impact on performance

Andrew Sheaff looks at new research on how habitual caffeine use in tea and coffee drinkers impacts the performance gains of caffeine supplementation – and how to maximize the benefits of caffeine supplementation regardless of caffeine use!

Caffeine is the mostly widely consumed psychoactive substance in the world. It is also the most commonly consumed substance with the potential to improve performance. As a result, caffeine has generated a lot of interest in the athletic community and the research community as potential ergogenic aid. What’s fascinating about caffeine is that it appears to be effective for athletes competing in explosive power events as well as long-duration endurance events. If there’s a possibility that a substance can improve performance, athletes are interested, and as caffeine appears to be beneficial across multiple disciplines, everyone is interested!

Habitual caffeine use

One of the challenges of understanding the impact of caffeine on performance is that most athletes are already consuming caffeine on a daily basis as part of their lifestyle, independent of their sporting activities. Therefore, it’s hard to know separate the impact of habitual caffeine from additional caffeine use as supplements. Caffeine also appears to be habit forming, and many individuals experience withdrawal when caffeine consumption is reduced or eliminated. Needless to say, substance withdrawal is certainly not an optimal performance state, causing mental and physical distress!

Because of the daily consumption of caffeine and its habit-forming nature, it’s difficult to determine if the use of caffeine can acutely enhance performance due to ergogenic properties, or if the use of caffeine is simply preventing the appearance of withdrawal symptoms. It’s important to make this distinction because it in turn informs potential strategies for consuming caffeine. If caffeine is enhancing performance by preventing withdrawal, then maintaining consistent caffeine intake is all that’s required to facilitate optimal performance in competition. However, if increased caffeine usage can provide additional benefits, athletes can then increase their intake prior competition to facilitate even better performances.

Prior research

A recent study was previously explored here in Sports Performance Bulletin in regards to habitual caffeine and performance. The subjects were assessed for their typical caffeine consumption and then performed trials with or without caffeine. Regardless of how much caffeine the subjects were consuming, they seemed to benefit from caffeine supplementation. Therefore, it was argued that habitual caffeine consumption does not negatively impact caffeine’s ability to acutely improve performance. However, as discussed above, it’s not clear if this improvement of performance with caffeine was a true improvement in performance, or merely that the use of caffeine simply prevented withdrawal symptoms in habitual users, allowing for improved performance.

As caffeine continues to be studied in more depth, there are still questions to be answered: What happens when athletes experience short-term caffeine withdrawal as compared to normal conditions? Does the duration of the caffeine withdrawal matter? Can withdrawal be reversed with caffeine consumption prior to performance? These are important questions that need answers.

New research

Recently, a research group in the United States sought provide more insight into the performance effects of caffeine in habitual caffeine consumers following a period of withdrawal(1). Ten recreational cyclists were recruited to the study; on average, the subjects were 39 years old, consumed 396mgs of caffeine per day, and had a V02max of 54.2 ml/kg/min. In other words, they were reasonably fit/trained cyclists who consumed a solid dose of caffeine every single day!

The participants in this study were only included if they consumed at least 250 mg of caffeine per day. This number was chosen because it is above the average daily caffeine consumption in the US, and withdrawal symptoms have been demonstrated at daily consumption levels of 100 mg per day or below(2). In other words, the researchers wanted to ensure that the subjects would definitely experience withdrawal symptoms without the presence of caffeine.

What they did

To determine the effects of caffeine on performance, the subjects were tested with or without caffeine withdrawal, and they were tested without or without pre-trial caffeine supplementation. To standardize the administration of caffeine, subjects consumed 3 mg/kg of caffeine at 12pm the day before each trial. As tests were all performed in the afternoon, this ensured that at least 24 hours would pass prior to the test. What’s unique about this study is that the withdrawal period is relatively short. The subjects only avoided caffeine for approximately 24 hours, as opposed to avoiding caffeine for multiple days.

On the morning of the trials, 8 hours before the test, subjects received either consumed a placebo or a dose of 1.5mgs/kg of caffeine. This created withdrawal symptoms in those receiving a placebo and avoided withdrawal in those consuming caffeine. One hour prior to testing, subjects received either 6mgs/kg of caffeine or a placebo. That meant subjects each performed four separate trials, which encompassed the following four conditions:

1. No caffeine in the morning and then no caffeine prior to testing.

2. No caffeine in the morning and then caffeine prior to testing.

3. Caffeine in the morning, but no caffeine prior to testing.

4. Caffeine in the morning and caffeine prior to testing.

Importantly, these tests were performed in a randomized order.

The participants performed the following tests in each of the four different conditions. The primary test was a 10-kilometer cycling time trial performed on a cycling ergometer. Prior to the time trial, the subjects also performed strength testing on an isokinetic dynamometer. This device moves at a constant speed and subjects aimed to create as much force as possible at a given speed. The cyclists performed two sets of 5 repetitions at three different speeds: 30°/s, 120°/s, and 240°/s. The purpose of the strength tests was to assess neuromuscular function.

The results

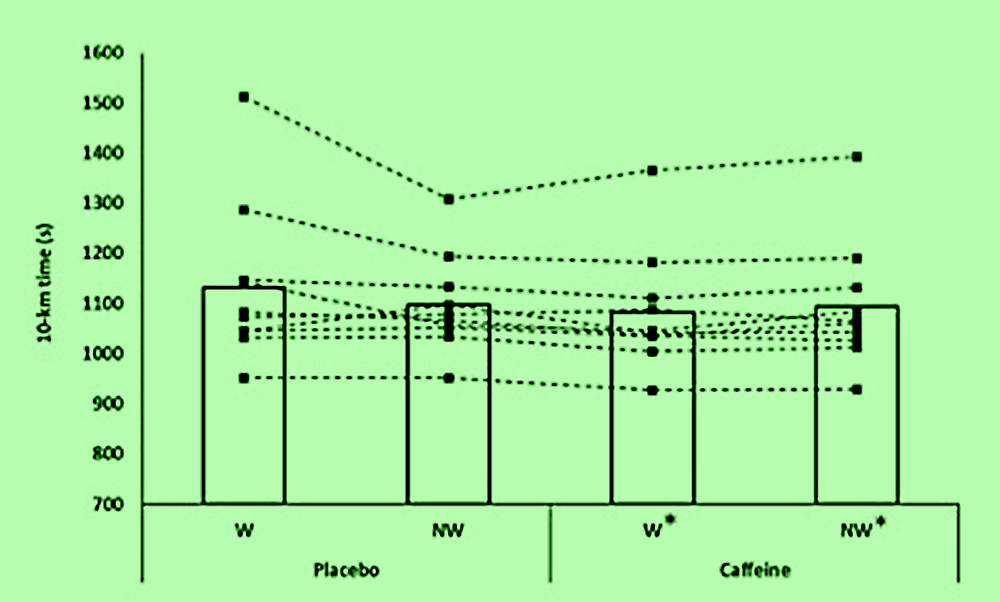

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the slowest time trial was when subjects had consumed no caffeine for 24 hours, with a mean performance time of 18mins:52secs. This was much slower than any of the other conditions suggesting a performance decline due to caffeine withdrawal (see figure 1). The third fastest time trial was when subjects consumed caffeine in the morning, but no caffeine before the trial with a mean performance time of 18mins:17secs. The second fastest trial was when caffeine was consumed at all points with a mean performance time of 18mins:13secs. The fastest trial was when caffeine was not consumed in the morning, but was consumed prior to the trial, with a mean performance time of 18mins:03secs (condition 2 above).

In terms of statistical significance, there was no difference in performance between trials where no caffeine was consumed immediately before the trial. There was a statistical significance between trials where caffeine was consumed before the trial as compared to when no caffeine was consumed at all (ie the 24-hour withdrawal trial – condition 1, figure 1). In this case however, the trials involving immediate pre-trial caffeine consumption did not differ between the trial where caffeine was consumed in the morning, but not pre-trial.

When it comes to neuromuscular function, the only significant difference that was found was that when subjects consumed both doses of caffeine, they were able to create more torque than when they consumed no caffeine at all. Further, this finding was only present when working at the slowest speed (30°/s). Because of this, any changes in performance are likely not due to changes in the ability to generate larger forces or torque.

Figure 1: Time trial times in the four conditions

In the placebo/withdrawal trial (ie no caffeine for 24 hours – condition 1 above), the times were markedly slower than all in the other trials, which produce statistically similar times. This suggests that caffeine withdrawal has a major negative effect in habitual users, and that they should ensure to continue using caffeine before competition!

Practical implications for athletes

Let’s decipher what these results mean in practical terms for athletes. The bottom line appears to be that if you’re a habitual consumer of caffeine, you should keep consuming caffeine in the morning of your competition, just prior to competition, or both. Doing so is likely to boost performance. This boost might not be due to a direct ergogenic effect however, but rather by mitigating the effects of caffeine withdrawal on performance. Either way, regardless of when you consume caffeine, just make sure you do it!

You may find that you feel and perform best when you emphasize caffeine in the morning of the competition, or by emphasizing consumption prior the competition itself. There’s no strong evidence that it’s likely to make a difference one way or the other beyond what you feel and perceive. You should consume caffeine in the manner that makes you feel best, thereby avoiding withdrawal; that pattern of caffeine consumption is likely to facilitate a great performance. While caffeine might not boost your performance, but it will ensure that your performance is maintained.

If you’re not a habitual caffeine user, it’s still possible that you will benefit from the consumption of caffeine in ways that habitual users do not. Unfortunately, that was not addressed in this study. If you’re interested in that potential, simply experiment with caffeine on the morning of challenging workouts, or prior to challenging workouts. If the results are consistently positive, it may be worth incorporating caffeine in a selective manner.

It still remains possible that different dosages or differently timed dosages may have a potent effect on performance. If you have a strategy that you believe works for you, continue to use it. It certainly won’t hurt performance. And if you’re up for continuing to search for more effective strategies, it very may well be worth the effort. Regardless, make sure you get your daily dose of caffeine to avoid withdrawal and maintain your performance. Finally, while it appears that there may not be a difference between taking caffeine in the morning or prior to competing, it may be best to play it safe and do both!

References

1. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2023 May 26;18(8):805-812. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2022-0350. Print 2023 Aug 1

2. Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;255(3):1123–1132. PubMed ID: 2262896

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.