Recovery nutrition: the perfect BCAA recipe?

There’s solid evidence that branch chain amino acids (BCAA) supplementation can aid post-exercise recovery as well as reduce muscle damage and soreness. But what is the optimum BCAA dosing regimen to achieve the best effects? SPB looks at new research

Full and rapid recovery is essential for any athlete that trains hard and competes regularly. The sooner full recovery takes place, the sooner he or she can engage in high-quality training or be ready to compete again. Achieving rapid recovery is vital in sports such as multi-day events or for example soccer, where fixture congestion can mean two or even three matches being played in a week.

Nutrition and recovery

Assuming an athlete gets adequate rest, the next single most important thing they can do to boost performance is to improve recovery nutrition. In very basic terms, good recovery nutrition will ensure that following requirements are met:

· Adequate carbohydrate – needed to synthesise and replenish muscle glycogen (the body’s premium grade fuel for strenuous exercise), and also to top up liver glycogen stores, which serve as a reserve to maintain correct blood sugar levels.

· Sufficient protein – needed to supply the amino acid building blocks required to repair and regenerate muscle fibres damaged during exercise, and to promote muscle hypertrophy (growth) and adaptation.

· Water – to replace fluid lost as sweat and to aid the process of glycogen storage in muscle (each gram of glycogen synthesised in muscle requires around three grams of water to ‘fix’ it in place.

· Electrolytes – to replenish minerals lost in sweat (eg sodium, chloride, calcium, magnesium).

Of these recovery requirements, the role of protein is especially important, being needed to repair and rebuild muscle fibers that are damaged and broken down during exercise, and also for muscle growth following an appropriate stimulus – eg a strength training session.

What are BCAAs?

Most of you reading this will know that all protein is composed of amino acid building blocks – the structural arrangement of which determines the protein type. There are around 20 of these amino acids found in protein foods, of which three are what is known as branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs – leucine, isoleucine and valine [see figure 1]). Like all amino acids, the BCAAs are required to build the thousands of proteins synthesized by the body. However, when it comes to building and maintaining muscle tissue, the BCAAs are especially important. Firstly, these amino acids are ‘essential’, meaning that we need to get them in our diet because our bodies can’t make them. Secondly, muscle tissue is disproportionately rich in BCAAs, making up around a third of muscle protein(1). Thirdly, studies on muscle metabolism during exercise show that BCAAs perform a crucial role, and can actually serve as a source of fuel, especially when carbohydrate stores in the muscle (glycogen) are running low(2).

Figure 1: The BCAAs

BCAAs and diet

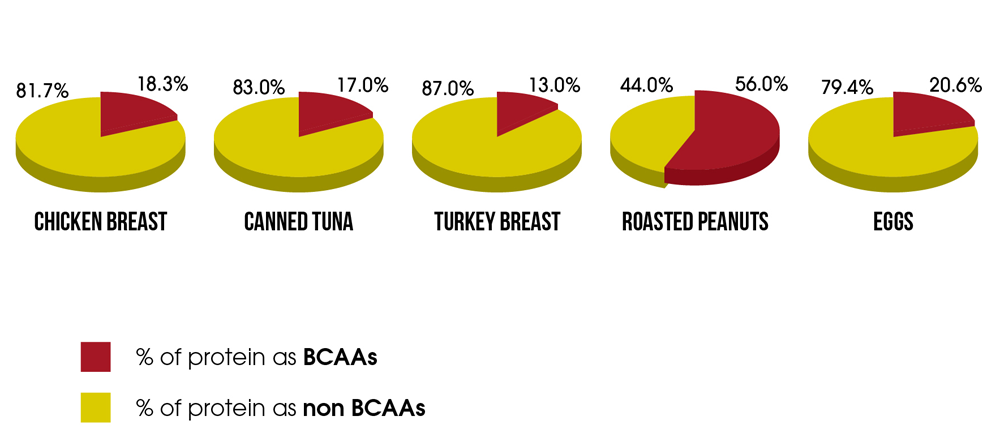

Because of the importance of BCAAs in muscle metabolism, especially in the context of exercise, the dietary intake of BCAAs for athletes has long been a topic of interest to sports nutritionists. It turns out that many protein-containing foods are also rich in BCAAs (see table 1 and figure 2), which means that BCAA intake is very much a function of day-to-day diet. Looking at figure 1, you can see that 100g of protein from many protein-rich foods will provide around 15-20g of BCAAs per day and some (like peanuts) even more. This relatively large figure helps explain why taking a BCAA supplement of just one or two grams per day is unlikely to be effective in providing benefits, something that has been observed in many studies.

Table 1: BCAA content of some protein-rich foods*

|

Food |

Serving(g) |

Protein |

Total BCAA |

Leucine |

Isoleucine |

Valine |

||

|

Chicken breast |

170 |

36g |

6.6g |

2.9g |

1.8g |

1.9g |

||

|

95% lean beef |

170 |

36g |

6.2g |

2.8g |

1.6g |

1.8g |

||

|

Canned tuna |

170 |

33g |

5.6g |

2.5g |

1.5g |

1.6g |

||

|

Wild salmon |

170 |

34g |

5.9g |

2.7g |

1.5g |

1.7g |

||

|

Beef steak |

170 |

36g |

6.2g |

2.8g |

1.6g |

1.8g |

||

|

Turkey breast |

170 |

40g |

5.2g |

2.8g |

1.1g |

1.3g |

||

|

3 eggs |

180 |

18.9g |

3.9g |

1.6g |

0.9g |

1.2g |

||

|

Roasted peanuts |

170 |

12g |

6.8g |

3.1g |

1.7g |

2.0g |

||

*Journal of Microbiology Biotechnology and Food Sciences, October 2015. 5(2):197-202

Figure 2: Proportion of protein as BCAAs in some protein rich foods

BCAA supplementation and recovery

Although a protein-rich diet contains adequate levels of BCAAs for health, some sports scientists have nevertheless wondered whether giving additional BCAAs in a pure supplemental form, especially before or after exercise, might confer an additional advantage in terms of recovery. As a result, a number of studies into BCAA supplementation and exercise have been carried out. For example, a 2012 study provided evidence that extra BCAA intake may directly regulate protein turnover in muscle cells to reverse the catabolic (breaking down) and muscle growth inhibiting consequences of exercise-induced muscle damage (EMID) – most likely by modifying post-exercise inflammation processes(3).

Evidence has also emerged that one of the BCAAs (leucine) plays a role as a key signalling molecule (mTOR), helping to activate genes associated with muscle growth(4,5). Furthermore, research suggests that BCAAs could potentially play a role as ‘recovery promoters’ in muscle tissues damaged by exercise(6). As a result of the potential of BCAAs to alleviate the negative symptoms of EIMD, the practice of BCAA as a supplementation has increased in popularity among active individuals and athletes over recent years(7).

The question of course is does BCAA supplementation really help to improve recovery and subsequent performance? Two quite recent review studies (studies that review the findings from a number of previous studies on a topic and summarize the findings) on BCAA supplementation concluded that it does appear to be a helpful strategy for recovery between workouts, and may therefore have a positive impact on subsequent exercise performance(8,9).

Despite these findings, there’s still controversy on whether supplementing with extra BCAAs really does confer a benefit. Although other review and meta-analysis studies (studies that pool the data from a number of previous studies and come up with findings based on statistical probability) have found that supplementing BCAAs can reduce muscle damage and post-exercise muscle soreness(10-15), some scientists argue that many of these studies were flawed or problematic; in some of these studies healthy active participants and studies including endurance-damaging protocols were excluded. Also, many of the supplementation protocols used BCAA supplementation combined with other ingredients such as protein, green tea, arginine and vitamins (A, E, and B6). Therefore, separating out the independent effect of BCAA supplementation was not possible to any meaningful extent.

Definitive research

To try and get a definitive answer on the benefits (or otherwise) of BCAA supplementation, an international team of researchers has carried out the most comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of BCAA supplementation on markers of muscle damage biomarkers and muscle soreness to date(16). Published in the journal ‘Sports Medicine – Open’, this analysis used strict criteria to select high-quality studies on BCAA supplementation and exercise, which allowed the researchers to calculate not just if there was a benefit to BCAA supplementation, but also how any benefits might vary at different time points following exercise, and with different BCAA dosage and supplementation durations. To achieve this, seven different medical databases were scoured for relevant studies on BCAA supplementation and exercise. Articles were only included if they met the following criteria:

*Full-text published peer-reviewed articles

*Studies used randomized controlled trials (parallel or crossover study design)

*Studies were performed on healthy active participants (no injuries, illnesses or any other medical conditions)

*Studies used BCAA as an intervention at least once and where there was a control group who either did nothing or took a placebo.

*BCAA supplementation took place either before or after (or both) the training task.

*The training task used either using resistance or endurance exercise to produce muscle soreness and damage.

*There was at least one assessment of muscle soreness/damage following the training protocol.

*The studies only used BCAAs (ie studies where other amino acids or other ergogenic substances were consumed were excluded).

Once the data was sifted, 18 articles were included in the final analysis, 13 of which were considered ‘high’ quality, with a further 5 judged as ‘medium’ or ‘acceptable’ quality. In the analysis, a number of sophisticated statistical techniques were used to pool the data and tease out the trends relating to BCAA use and muscle soreness/damage.

The key findings

When the data from these 18 studies was pooled and analyzed, the following key findings emerged:

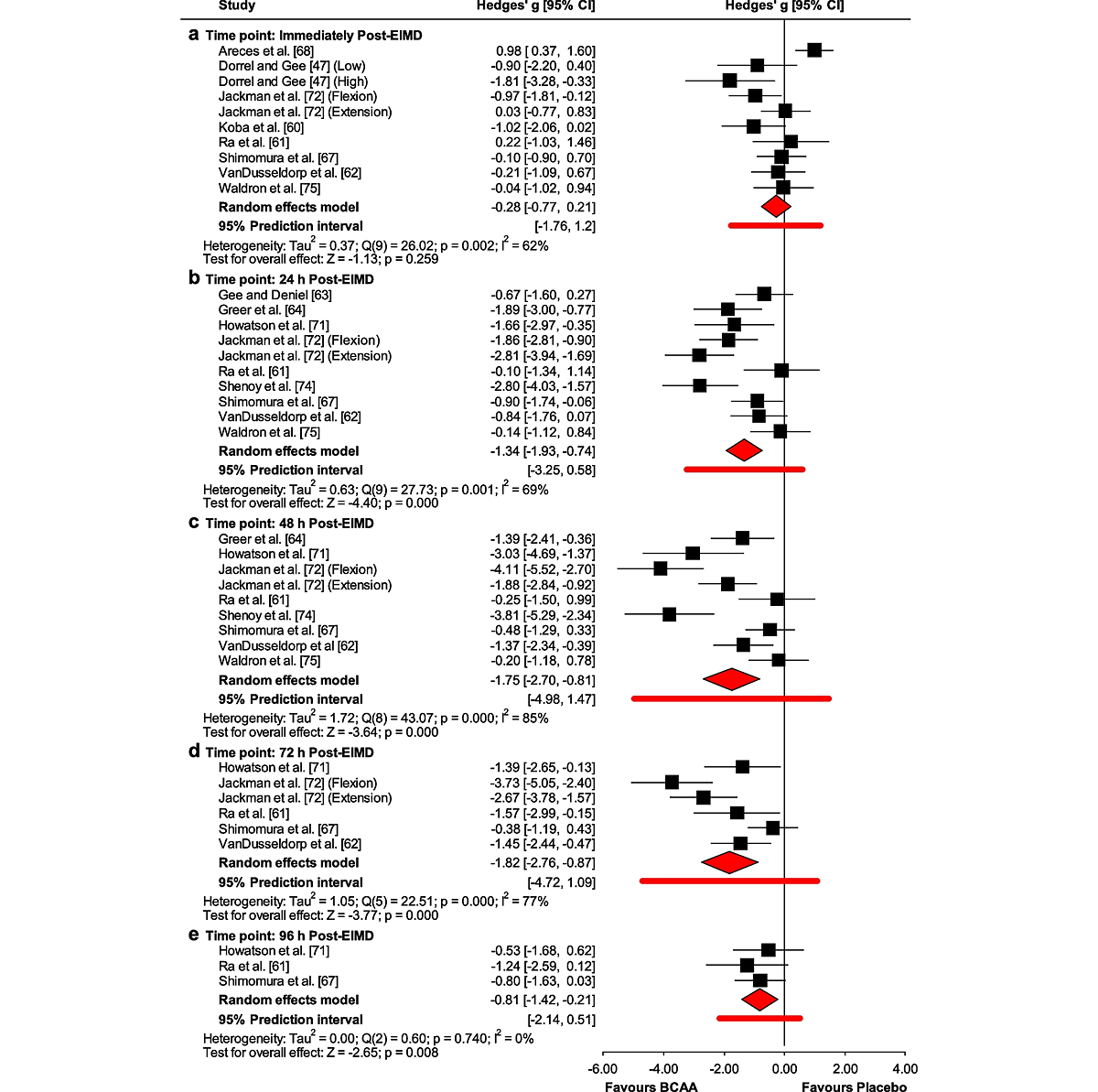

· BCAA supplementation did appear to reduce muscle soreness (see figure 3) and muscle damage (measured by a key marker of damage known as ‘creatine kinase’.

· The degree of reduction in soreness and muscle damage varied somewhat according to the participants; male athletes seemed to gain a greater benefit overall than female athletes, while those who were well training got greater reductions in muscle soreness immediately after and at 48 hours after training, whereas those who were less well trained got greater benefits at 24 hours post training.

· A long BCAA supplementation period of 7 or more days was significantly more effective at providing benefits compared to when BCAAs were taken for 6 days or less.

· High dosages of 5 or more grams were more effective than smaller doses.

Figure 3: Effectiveness of BCAA supplementation for reducing muscle soreness

NB: from top (a) to bottom (e) shows the reduction in muscle soreness after 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours. Each black square shows data from one of the individual studies included in the analysis. The red diamond shows the average result for that time period. The diamond width shows the degree of uncertainty in the findings. Diamonds and squares to the left of the zero line (ie negative) show a positive effect for the benefits if BCAA supplementation. Where the whole diamond lies to the left of the zero line (ie all the time points except 0 hours), there is a high degree of certainty that BCAA supplementation reduces muscle soreness. The individual studies shown in this graphic can be found in the references listed in the Sports Medicine – Open article here.

In their summing up, the authors of this study concluded that BCAA supplementation seems to reduce muscle damage within the first 24 hours post exercise and again at 72 hours. It also reduces delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) from 24-96 hours post exercise, which means BCAA supplementation can be used as an effective strategy to accelerate the recovery process after intense exercise. They also added that when athletes take BCAAs after a bout of intense exercise, taking higher doses for longer (ie a higher total dosage) seems to offer the best results.

Implications for athletes

What do these findings mean for athletes in hard training? The first thing to say is that this latest research gives us a very high degree of confidence that supplementing BACCs either before or immediately after strenuous training sessions does help to reduce both exercise-induced muscle soreness and muscle damage. However, this needs to be qualified because it seems that the best effects are had when quantity of BCAAs supplemented is around 5g per day at a minimum.

Another caveat is duration of BCAA supplementation; regular supplementation of BCAA for seven days or more seems to provide the best protection, whereas (for example) a one-off dose after a hard training session is unlikely to give an athlete significant benefits. During periods of high-load training therefore, BCAA supplementation should be considered as part of a daily nutrition regimen rather than taken after particular training sessions.

Finally, it’s worth adding that since there are a number of protein foods that are naturally rich in BCAAs, it makes sense if athletes can consume these on a regular basis as part of their daily diet as doing so will help top up BCAA reserves in the body. Whey protein is one of the protein foods that is rich in BCAAs; therefore if you are a daily whey protein drink user who consumes 30 grams or more or pure whey protein per day in addition to other sources of dietary protein (ie as protein and recovery shakes), you will probably get little additional benefit from taking a dedicated BCAA supplement because you are in effect already supplementing your diet with at least 5 grams of BCAAs per day, albeit in a slower released form (since that whey needs to be digested first)!

References

1. Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20:457–83

2. J Nutr Health Food Eng. 2019;9(3):128–33

3. J Nutr Metab. 2012:2012:136937

4. J Nutr. 2005;135(6 Suppl):1580S-S1584

5. ‘Nutrition and skeletal muscle’: Gorissen SH & Phillips SM. Elsevier; 2019. p. 283–98

6. Nutrients. 2017;9(10):E1047

7. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2011;8:23

8. J Nutr Health Food Eng. 2019;9(3):128–33

9. Nutrients. 2022;14(19)

10. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2021;46(11):1303–1

11. Sport Sci Health. 2019;15(2):265–79

12. Nutrients. 2021;13(6):1880

13. Nutrition. 2017;42:30–6

14. J Nutr Fast Health. 2020;8(1):1–16

15. Amino Acids. 2021;53(11):1663–78

16. Sports Med Open. 2024 Apr 16;10(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s40798-024-00686-9

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.