Sodium citrate: move over bicarb?

Sodium bicarbonate has long been used as a performance enhancing supplement for high-intensity events, but could sodium citrate offer the same benefits with fewer side effects? SPB looks at brand new research

Many athletes will no doubt be familiar with the use of sodium bicarbonate as a performing enhancing supplement. Indeed, you may have even used it yourself! The use of sodium bicarbonate first became popular in the early 1980s following research that showed that by helping to buffer the acidity produced in muscles during very intense exercise, pre-exercise bicarbonate was able to help stave off some of the fatiguing effects of high (lactic) acid accumulation, thereby enhancing performance in events lasting between 1-5 minutes(1,2).

During the rest of the 1980s, bicarbonate use became popular among athletes involved in high-intensity, anaerobic events, such as 800m and 1500m runners, 200m and 400m swimmers etc. However, unlike other sports supplements for boosting high-intensity performance, the popularity of bicarbonate waned and eventually fell out of favour. This was because many athletes discovered that its use was often accompanied by unpleasant side effects such as nausea and gastric distress – severe enough in many cases to be counterproductive. This loss of popularity was no doubt aided by the emergence of the supplement creatine in the 1990s, which provided sprint, strength and high-intensity athletes with another nutritional tool for improving performance, and without the issue of side effects(3,4).

Bicarbonate revisited

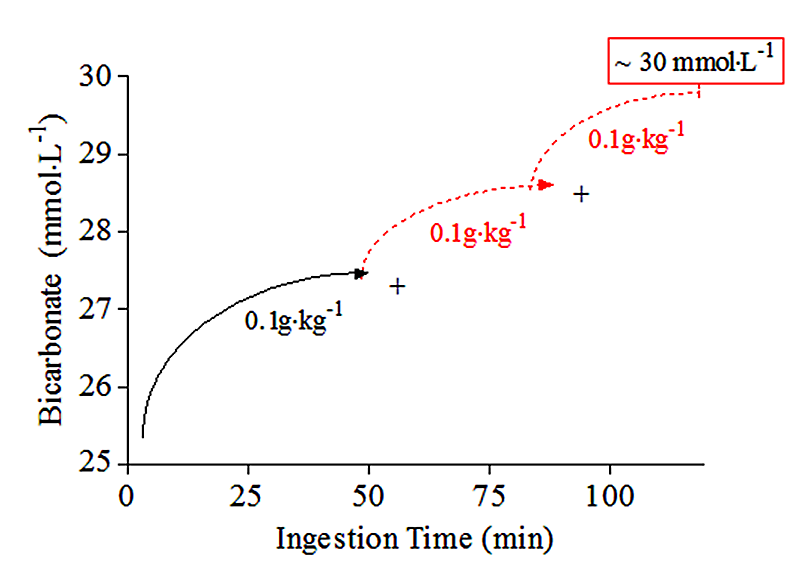

Regular SPB readers will be aware that over the past decade or so, there’s been a renewed interest in bicarbonate supplementation. That’s because research has demonstrated that that with careful administration, many athletes may find that they can reap the benefits of bicarbonate while minimizing the side effects. In particular, a staged intake (spreading the intake over a 90-minute period rather than consuming the bicarbonate in one hit – see figure 1) appears to be much better tolerated by the tummy(5). In addition, consuming the required amount (usually put at 0.3 grams per kilo of body weight – around 20 grams for a 70kg athlete) much earlier before exercise takes place also seems to reduce gastric distress without impacting on the potential benefits (see this article for an in-depth discussion).

Figure 1: Using a staged approach to bicarbonate ingestion

Despite this renewed interest in bicarbonate supplementation, many athletes are still reluctant to incorporate it into a supplementation program. There are two main reasons for this: firstly, while a staged approach reduces the likelihood of side effects, gastric distress still remains a significant problem for some athletes. Secondly, while not complicated, a staged bicarbonate dosing protocol is far from convenient, requiring the athlete to consume carefully measured and equal boluses of bicarbonate every 30 minutes in the run up to exercise – something that may be far from practical when used prior to an event or competition.

A citrate solution

Is there anything that can fulfil the role of sodium bicarbonate but without the side effects or dosing complexity? Around the year 2000, a handful of studies looked at using pre-exercise sodium citrate supplementation (see box 1) as an alternative to bicarbonate in an effort to see if gastric distress could be reduced. These studies used 0.3-0.5 grams per kilo of bodyweight of sodium citrate in runners and cyclists, and did report a reduction of gastric distress symptoms, but with mixed performance results; two studies reported significant performance gains from citrate(6,7) while a third reported no gains(8).

Box 1: What is sodium citrate?

Pure sodium citrate is a white, crystalline powder or granular crystals, which readily dissolve in water. Rather like the citric acid used in many sports drinks to add ‘tang’, sodium citrate has a rather bitter/acid taste. However, unlike citric acid, sodium citrate is not acidic and can actually help to combat acidity by soaking up and neutralizing excess acid in the blood and urine.

When sodium citrate is ingested and absorbed, it dissociates into sodium and citrate ions. These citrate ions are then metabolized to bicarbonate ions, resulting in an increase in the blood bicarbonate concentration. This increase in blood bicarbonate is able to mop up excess hydrogen ions (what causes acidity), thus making the blood more alkaline.

In effect then, sodium citrate is able to help mop up the excess of hydrogen ions generated during intense activity, reducing lactic acid induced fatigue, which is how sodium bicarbonate also works. The difference is that instead of ingesting bicarbonate directly (which can cause a lot of gastric distress), the bicarbonate is generated by metabolism of citrate within the body.

Strangely however, the research into supplemental citrate faded following this early research. A 2011 study found that sodium citrate produced an equal alkalizing effect to sodium bicarbonate, but did not however study performance effects(9). A 2018 study on swimmers meanwhile compared the ingestion of sodium bicarbonate vs. sodium citrate for performance in the 400m freestyle event when ingested 90 minutes prior to exercise(10). It concluded that while sodium bicarbonate produced performance benefits (shaving around 0.6% off times), the citrate did not improve performance but instead resulted in a decrement of around 0.2%.

On the face of it, sodium citrate supplementation (instead of bicarbonate) looks to be a questionable strategy, with mixed results at best. However, some scientists have pointed out that because sodium citrate requires extra time for metabolic conversion into bicarbonate once in the body (ie it takes longer for blood alkalinity to increase), comparing bicarbonate and citrate using the same protocol is pointless. In reality, citrate ingestion would need to take place much earlier than 90 minutes prior to exercise.

New citrate research

In an effort to answer the citrate question (does it really boost performance while reducing side effects?), a team of Turkish research have carried out a study on pre-exercise citrate supplementation for repeated sprint performance in soccer players(11). Published in the highly esteemed Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, this research into citrate and performance differed because citrate ingestion took place not 90 minutes prior to exercise but a whole three hours beforehand.

In this study 20 well-trained soccer players performed a running-based anaerobic sprinting study, which was designed using a randomized, crossover, double-blind format (the most scientifically rigorous design). The soccer players performed two identical trials in a random order consisting of repeated sprint intervals. During these trials, the researchers recorded the average power output of the players and by how much performance declined during each trial. The only difference between the trials was what the players ingested three hours beforehand:

· Sodium citrate trial – a drink containing 0.5 grams of citrate per kilo of body weight.

· Placebo trial – an identical tasting drink containing a small amount of sodium chloride (table salt).

After the first trial, there followed a 6-day washout and recovery period whereupon the trial was repeated with the second condition (ie players who had taken citrate in the first trial took placebo in the second and players who had taken placebo now took citrate in the second trial). Blood samples were collected before exercise and at first, third, fifth, and seventh minute after exercise to analyze blood acidity/alkalinity, bicarbonate, and lactate levels. Gastrointestinal symptoms were also monitored every 30 minutes following ingestion of the per-exercise drinks right up until exercise commenced. Importantly, the performance results from each player were analyzed in each condition to calculate whether the citrate had delivered a performance benefit.

What they found

The first finding was that (unsurprisingly) the players’ blood alkalinity and bicarbonate levels were higher compared to placebo during the sprint trials when the citrate had been consumed. When it came to gastrointestinal side effects, consuming the citrate resulted in more symptoms than the placebo during the first 60 minutes after ingestion, but there were no significant differences at 90, 120, 150, or 180 minutes. In other words, any side effects disappeared a long time before exercise commenced.

But what about the players’ performances? Here, the citrate ingestion showed significant performance gains; when the players ingested citrate three hours before exercise, their average power output rose, and their performance decrement (drop in performance as the repeated sprints progressed) was reduced – allowing them to maintain more of their speed and power in the sprints up to the end of the trial.

Implications for athletes

The results from this new research suggest that citrate could indeed provide performance benefits for athletes in high-intensity events, especially where repeat sprint performance is required – eg soccer and other field sports. Is sodium citrate superior to sodium bicarbonate in terms of performance gains? We can’t answer that because the two were not compared directly. Having said that, it’s likely the benefits are similar because the increases in blood alkalinity observed three hours following citrate ingestion were comparable to those seen 90 minutes after bicarbonate ingestion.

What we can say however is that the citrate ingestion caused no gastric distress issues during the sprint trials because any side effects experienced had worn off two or more hours prior to the sprint trial. This is a big plus over bicarbonate, where even the staged ingestion protocol leaves some athletes experiencing gastric distress during exercise. In a sense then, taking sodium citrate three hours beforehand allows any gastric effects to dissipate well before exercise begins, yet (due to conversion into bicarbonate in the blood) still produces the kind of blood alkalinity gains that are needed to enhance exercise performance.

Should you experiment with sodium citrate? Assuming you’re a sprint or middle distance athlete who is well trained and looking for that extra performance edge during competition, the answer is ‘maybe’. If you’ve tried using sodium bicarbonate in the past but have experienced gastric issues during your event, sodium citrate might help you get round the problem and still deliver performance benefits. It’s also easier and simpler to take citrate in one hit than staging bicarbonate intake over 90 minutes. However, if you have or are using bicarbonate successfully and without side effects, there’s probably little to gain from trying citrate (other than convenience).

If you do try sodium citrate, remember that you must take it three hours before exercise. That’s because at takes a while for the citrate to be metabolized into bicarbonate. In the study on swimmers above(10), it was clear that 90 minutes before exercise was not sufficient for this to occur. In terms of practicalities, sodium citrate is cheap and readily available, and there are no real downsides to its use other than temporary gastric symptoms (which should completely disappear well before exercise). However, given the nature of these types of supplements, it’s essential that you trial citrate supplementation out in training a few times first before using it for competition to be sure it works for you. Never experiment for the first time on the big day!

References

1. Int J Sports Med. 1984 Oct;5(5):228-31

2. Sports Med. 1984 May-Jun;1(3):177-80

3. Clin Sci (Lond). 1993 May;84(5):565-71

4. Sports Med. 1994 Oct;18(4):268-80

5. J Strength Cond Res: July 2012 - Volume 26 - Issue 7 - p 1953-1958

6. J Strength Con Res 2001; 15, 230

7. Int J Sports Med 1996; 17, 7

8. Eur J Appl Physiol 2000; 83, 320

9. Sports Med. 2011 Oct 1;41(10):801-14

10. J Hum Kinet. 2018 Dec; 65: 89–98

11. J Strength Cond Res. 2024 Jan 19. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000004651. Online ahead of print

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.