You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Body composition and sport: why weight is a poor performance indicator

The bathroom scales might tell you how much is there, but they don’t tell you what is there. Knowing your body composition, and more specifically your body fat level, allows you to plan and measure the outcomes of your training and dietary programmes more accurately, writes James Marshall.

The human body is composed of many different substances all of which are necessary for us to function. These include water, muscle, bone, organs and fat. But while fat is an essential part of the human body, necessary to provide energy for long- duration athletic endeavours, as well as insulation against cold temperatures and the protection of vital organs, it is often portrayed as an undesirable element that must be eliminated at all costs.

In health terms, too much fat is associated with diabetes and coronary heart disease, while the reduced power-to-weight ratio it produces inevitably leads to impaired athletic performance. A very simple measurement of ‘fatness’ can be performed to determine whether there’s an increased risk of coronary heart disease and other obesity-related illnesses. This is body mass index (BMI), defined by body weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres. For example, an 80kg athlete who is 1.78 metres tall would have a BMI of 80 divided by 1.782, or 25.2. Individuals with a BMI over 27 are considered to be at a significantly greater risk of health problems than those under 27.

Conversely, female athletes who have very low BMIs (18 and below) may be at risk of developing irregular menstrual cycles (1). Those females with low overall body weights may also be at greater risk of developing osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis, a disease characterised by decreased bone strength and a reduction in overall bone mineral content (BMC) is most common in postmenopausal women, but also in those with sedentary lifestyles and those whose diets are calcium deficient. Actual body weight has been shown to be a better indicator of BMC than body composition in women of all ages, with heavier women having higher BMC values (2). However, measuring body composition can help female athletes achieve a healthy body weight that reduces risk of osteoporosis and irregular menses, but allows optimum performance and reduces the risk of coronary heart disease and diabetes by being over-fat.

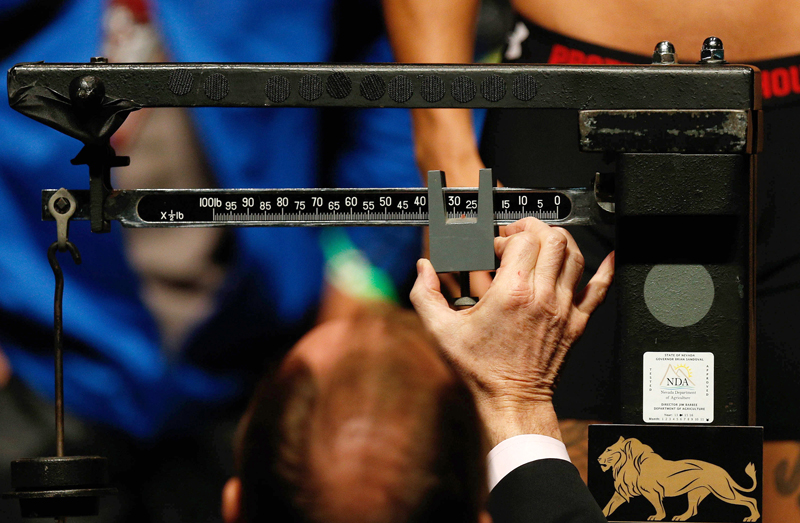

Measuring fat

Simply measuring your weight by standing on a set of scales does not allow you to determine whether you have an optimal level of fat in your body for your age, sex and chosen sport. Moreover, athletes who are resistance trained are more likely to have greater amounts of fat-free mass, and therefore be heavier than the non-athletic population, so BMI is not always an accurate tool for sports people.For example, a recent study of US National Football League (NFL) players compared current players with those of 30 years ago, across a wide range of body composition measurements including height, weight, fat-free mass and BMI (3). The average BMI for the current defensive linemen was a whopping 34.6, based on an average height of 1.92 metres and weight of 127kg. However, their average body fat percentage was only 18.5, just within healthy limits of the normal population (see table 1 below).

| Classification | ||

| Women | Men | |

| Essential fat | 11-14 | 3-5 |

| Athletes | 12-22 | 5-13 |

| Fitness | 16-25 | 12-18 |

| Potential risk | 26-31 | 19-24 |

| Obese | 32 and higher | 25 and higher |

How does training influence body composition?

If you decide to set a weight target and how much or little of that weight should be fat, what can you do to achieve your goal? The good news is that a combination of diet and training will allow you to change your body composition. The bad news is that it requires a consistent approach and also that any change is not permanent, but can easily be reversed if old habits are revisited.*Measuring body fat percentage

Body fat percentage can be determined by several methods, all of which try to measure what percentage of your overall body mass is fat (and what is lean tissue). These methods include:*Hydrostatic weighing

requires the use of a tank that allows the subject to be measured underwater. A comparison is made between the underwater weight and the dry weight of the subject, taking into account the residual volume of air in the lungs, which affects buoyancy. Because fat is less dense than the other tissues in the body, it floats more easily. The more fat an athlete has, the greater the difference between the dry and wet weights. This is a very accurate measurement, but is time- consuming, labour intensive and not readily available for most populations.*Bioelectrical impedance analysis

measures the level of resistance of current through the body. Since water conducts electrical current well, those tissues with higher water levels (muscle) conduct electricity better than those with lower levels (fat). By determining the impedance to electrical current flow, an estimate is made of the percentage of fat in the body. This measurement is quite accurate, but is affected by the level of hydration of the subject, so those subjects who have drunk alcohol, caffeine or have exercised within the previous 12 hours may be dehydrated and not get accurate readings. Females may get different measurements at different points of their menstrual cycle due to water retention (5).*Skinfold callipers

are used to measure the levels of subcutaneous fat at different sites around the body. Common sites used are the triceps, biceps, subscapular, suprailiac and the thigh. The tester measures the site by pinching the fat away from the subject’s body and then placing the callipers halfway between the base and the apex of the fold. A reading is then taken in millimetres. The sum of these skinfolds is then entered into an equation and a body fat percentage obtained. Consistent measurements of skinfold sums are possible, but this requires the location of the sites on the body to be accurately determined, and properly trained and skilled technicians.Location for subscapular skinfold

Location for suprailiac skinfold

All three of these methods make certain assumptions in the equations that are used and errors can be made when using these assumptions for different populations. Bone density varies between different ethnic groups and in different age groups of the same ethnic background, so the formulae used in underwater weighing and bioelectrical impedance may not be accurate for non-white subjects, children or the elderly.

A lot of sportsmen and women assume they have nothing to worry about; they exercise hard, eat what they want and keep in good shape. However, this approach may be a bit haphazard, because although overall weight may stay the same, body composition can change and could indicate a change in performance. Take wrestling and rugby league over the course of a season, for example, and we can see that body composition is not always a constant measure.

College wrestling in the USA is a seasonal sport running from October to March and consisting of between 20 and 30 matches. Wrestlers are put in weight categories, so body composition is constantly monitored to ensure that the wrestler is not carrying excess fat, which would hinder performance.

In a study of 10 US division III college wrestlers, various body composition measures were taken, pre-, mid- and post season, as well as muscular strength and muscular power tests (7). Body fat percentage and body weight did not change significantly throughout this study, with the wrestlers having an average weight of 67.5kg and 10.5% body fat midway through the season. Muscular power stayed the same throughout the season, but muscular strength declined slightly.

However, changes in body composition did occur in a study of 52 rugby league players in Australia over their season from April to August, following a pre-season that started in December (8). Players had their sum of skinfolds measured as well as their maximal aerobic power, and maximal muscular power, at four stages of the year:

- Off season;

- Pre-season;

- Mid-season;

- End of season.

Body weight and body composition are key factors in college wrestling because wrestlers need to maintain a constant weight in order to enter their fighting categories. By contrast, these factors are not the main focus in rugby league, where any decline in fitness and increase in body fat at the end of the season would occur just at the time when matches become more intense as cup competitions come to their finale, and end of season play-offs and promotion/relegation battles come to a head.

In short, playing the sport of your choice does not ensure that your body composition, or other areas of fitness, remain stable. However, by measuring body composition you can determine whether your levels of fat are remaining constant or are changing, and you can therefore implement an in-season training and diet programme accordingly.

Managing and measuring your body composition

A combination of diet and training can help you control your body composition, but there are many behavioural factors involved, and any behavioural change will be aided by support and education from outside sources such as your family, friends, peers and coaches. A simple resistance training programme of a 75-minute training session, three times a week with diet control has been shown to increase fat-free mass and bone mineral content in obese children (9) in just six weeks. However, changes to your body composition may not be that simple and will depend on your current level of training, how much time you have, and how easy it is for you to change your diet. Whichever route you take, there’s no escaping the laws of chemical thermodynamics; for each pound of body fat you want to shed, you’ll need to create a 3,500kcal deficit, by increasing your energy output (longer, more frequent or more strenuous training sessions), cutting back your calorie intake, or by a combination of the two.Measurement strategy

One of the most simple and reliable ways of measuring your body composition is to calculate the sum of your skinfold measurements from four or five sites around your body. You can then compare this with the sum in the future when you remeasure yourself. However, you’ll need a pair of skinfold callipers and an assistant who can measure the sites.The most common sites are the biceps, triceps, subscapular and suprailiac, but the British Olympic Association also recommends that a lower body site such as the front of the thigh also be measured and included (10). By using the sum of skinfolds, rather than converting to body fat percentage using equations, you can eliminate the errors inherent in the conversion equations but still have a useful measure of your subcutaneous fat levels.

For example, suppose the five sites give you a skinfold total of 45mm. You decide that this corresponds with a low level of fitness and performance and feel that you should lose some fat. You then implement a six- week programme of diet control and an additional 30 minutes of low- intensity cycling twice a week. You retest and find that the sum of skinfolds has dropped to 39mm. You may then decide that your ideal score is somewhere between 35 and 39mm and try to maintain that throughout the year.

A consistent approach to body composition monitoring matched with appropriate training can help prevent a boom and bust cycle of fat gains/losses and performance declines as the season progresses. It will help you to maintain a healthy body composition, and improve your performance in the off season, pre-season and in season.

James Marshall MSc, CSCS, ACSM/HFI runs Excelsior, a sports training company

References

- Journal of Sport Sciences 1998; 16(7):629-637

- AHB 29(5):559-565

- Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2005; 19(3):485-489

- Annals of Human Biology 1999; 26(2)179-184

- Howley and Franks (1997) Health Fitness Instructor’s Handbook, Human Kinetics

- Journal of American Geriatric Society 1997; 45(7):837-843

- JSCR 2005; 19(3):505-508

- JSCR 2005; 19(2):400-408

- JSCR 2005; 19(3):667-672

- JSS 2003; 21(5)369

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.