Running and body fat - walking the tightrope of optimum performance

Professor Ron Maughan explains how runners can reduce body fat while ensuring optimum health and performance

Professor Ron Maughan explains how runners can reduce body fat while ensuring optimum health and performance

Although it’s immediately apparent that there are substantial differences in physical characteristics between sprinters and long distance runners, elite runners at all distances come in a variety of shapes and sizes, and there are perhaps too many exceptions to make all but the broadest generalisations.

Generally speaking though, sprinters have powerfully developed musculature of the upper body and of the legs, while distance runners have low body mass, with smaller muscles and extremely low body fat levels.The one outstanding anthropometric characteristic of successful competitors in all running events is a low body fat content. The textbooks tell us that the body fat stores account for about 15-18% of total body weight in normal young men, and in young women the figure is about 25-30%.

‘Normal’, of course, is changing, and those ranges should be qualified as being normal for healthy people. Most of this fat is not necessary for energy supply and is simply extra weight that has to be carried throughout the race. This is not to say that people carrying extra fat cannot complete a marathon – they just can’t do it in a fast time.

Our fat stores are important and the fat cells play many key roles. As well as acting as a reserve of energy that can be called upon at times of need, fat is important in the structure of tissues, in hormones metabolism, and in providing a cushion that protects other tissues.

An excess of body fat, however, serves no useful function for the endurance athlete. It can help the sumo wrestlers, and perhaps may not even be a disadvantage for the shot putter, but not the runner. Extra fat adds to the weight that has to be carried, and thus increases the energy cost of running. Even in an event as long as the marathon, the total amount of fat that is needed for energy supply does not exceed about 200g for the average runner.

A very lean male 60kg runner with 5% body fat will have 3kg of fat; a typical elite 55kg female runner with 15% body fat will have more than 8kg of body fat. Non-elite runners will commonly have at least twice this amount, and many runners further down the field will be carrying 20kg or more of fat.

Although not all of this is available for use as a metabolic fuel, the amount of stored fat is greatly in excess of that which is necessary for immediate energy production. Within limits, reducing this will lead to improvements in performance, but if the loss is too sudden or too severe, then performance and health may both suffer.

It is probably not sensible for men to let their body fat levels go below about 5% and for women below about 10-15%. There’s good evidence that the immune system is impaired when body fat stores are too low (1). A reduced ability to fight infections means more interruptions to training and more chance of being sick on race day.

For female athletes, there are some very immediate consequences of a low body fat level, including especially a fall in circulating oestrogen levels (2). This in turn can lead to a loss of bone mass, causing problems for women in later life through an increased risk of bone fracture. Equally, though, performance will suffer if the body fat level is too high, so staying healthy and performing at peak level is a real challenge.

Fat typically contributes about half of the total energy cost of a long run (this is very approximate, and will depend on speed, fitness, diet and other factors). At low running speeds, the total energy demand is low and most of the energy supply is met by oxidation of fat, with only a small contribution from carbohydrate in the form of muscle glycogen and blood glucose (which is continuously being replaced by glucose released from the liver).

As speed increases, the energy cost increases more or less in a straight line, but the relative contribution from fat begins to decrease, with muscle glycogen becoming the most important fuel. The problem with running slowly to reduce body fat levels is that it takes a long time, because the rate of energy expenditure is too low. Run too fast, and you burn only carbohydrate, leaving the fat stores more or less untouched.

Importance of fat

To get an idea of the importance of fat, you can try the following sums. For simplicity, we’ll assume that:

- The energy cost of running is about 1 kilocalorie per kilogram body mass per kilometre;

- The energy available from fat oxidation is 9 kilocalories per gram;

- About half of the energy used in a run will come from fat (this amount will actually be greater at low speeds and for fitter runners, and will also be higher if the run is completed after fasting overnight as opposed to just after a high carbohydrate meal).

Example 1

If you weigh 50kg, the total amount of energy you will use in a 10km run is 50x10 = 500kcals. If all of the energy were to come from fat, this would use 500/9 = 56 grams of fat. Half of this is 28 grams fat (almost exactly one ounce in old units).

Example 2

If you weigh 80kg the total energy cost of running a marathon (42.2km) is 80x42.2 = 3,376kcals. If all of the energy were to come from fat, this would use 3,376/9 = 375 grams. Half of this is 188 grams or around 7oz.

Three things emerge from this:

- The amount of fat you need for even a marathon is small compared to the amount stored; a 70kg runner with 20% body fat has 14kg of stored fat. A 60kg runner with 30% fat has 18kg.

- Even though the amounts of fat used may seem small, regular running will nibble away at the fat stores – good news if your aim is to use exercise to control or reduce your body fat levels. A runner who uses 28 grams three times per week will lose about 3.5kg of fat over the course of a year. The results are not immediate but, if you persist, the cumulative results are impressive.

- Running speed does not figure in the equation. If you run for 40 minutes, you might do 5km or you might do 10km.

Body fat and performance

In a study of a group of runners with very different levels of training status and athletic ability, scientists observed a significant relationship between body fat levels and the best time that these runners could achieve over a distance of 2 miles(3). Although these results indicated that leaner individuals seem to perform better in races at this distance, some complicating factors have to be taken into account.

The relationship between body fat and race time may at least in part be explained by an association between the amount of training carried out and the body composition. It would hardly be surprising if those who trained hardest ran fastest, and it would also not surprise most runners to learn that those who train hardest also have the lowest fat levels. Indeed, body fat content does tend to decrease as the volume of training increases, as we found out some years ago when we studied a group of local runners in Aberdeen (4).

We recruited a group of runners who had been running for at least two years, and asked some sedentary colleagues to act as a control group. All had maintained the same body weight for at least two months before we measured them, and all had had a constant level of physical activity over that time. We measured body fat levels and also got a record of the weight of all food and drink consumed over a one-week period.

The runners covering the greatest distance in training had the lowest body fat levels. They also ate more food than those who did less running. There are, of course, some people who do not fit the line as well as others, but there are many factors that explain this variability. We would expect the people who eat more to be fatter, but no! The subjects who did most running had the lowest levels of body fat, even though they did eat more. Thus, we can separate food intake from body fatness if we add exercise to the equation.

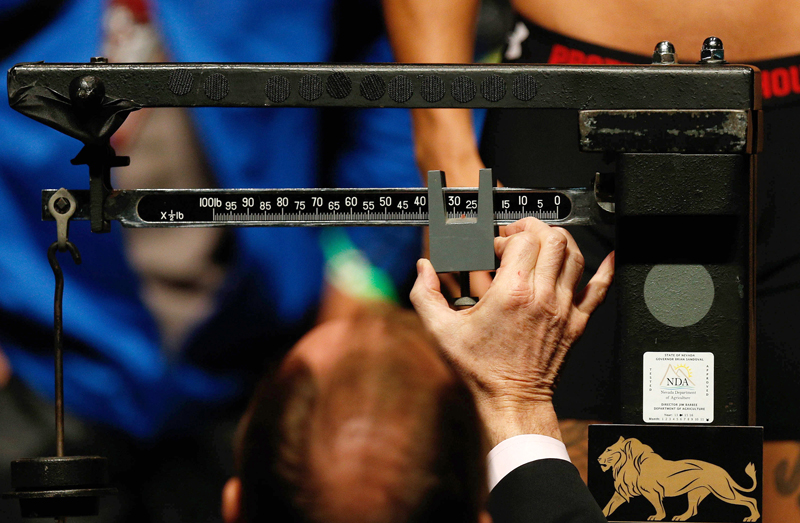

How is body fat measured?

There are problems in applying the standard methods for assessment of body composition to athletic populations, and it is not clear that any of the methods commonly used for the general population is entirely reliable. At health clubs and elsewhere, fat levels are usually assessed by use of skinfold callipers to measure the thickness of the fat layer that lies below the skin at various different sites on the body. The results are then fed into an equation that predicts the body fat level based on a comparison with more accurate measurements made on a group of ‘normal’ people. Predictive equations for estimating body fat content based on indirect methods are unreliable for several reasons, not least because the equations that are generated from normal populations are not applicable to elite athletes. Such methods have been widely used, but the results of these measurements must be treated with caution, especially if you are an athlete.

Fat levels in elite runners

Skinfold thickness estimates of body composition in 114 male runners at the 1968 US Olympic Trial race gave an average fat content of 7.5% of body weight, which was less than half that of a physically active but not highly trained group (5). Since then, similar measurements have been made on various groups of runners, and the findings are fairly consistent.

The low body fat content of female distance runners is particularly striking; values of less than 10-15% are commonly reported among elite performers, but are seldom seen in healthy women outside sport. The occasional exceptions to the generalisation that a low body fat content is a pre-requisite for success are most likely to occur in women’s ultra-distance running, and some recent world record holders at ultra-distances have been reported to have a high (in excess of 30%) body fat content. However, this probably reflects the under-developed state of women’s long distance running; as more women take part, the level of performance can be expected to rise rapidly, and the elite performers are likely to conform to the model of their male counterparts and of successful women competitors at shorter distances.

Although there’s an intimate link between body fat levels and running performance, it’s important to remember that reducing fat levels will not automatically guarantee success and may even be counter-productive. If you reduce fat by a combination of training and restricting diet, you are walking a fine tightrope. While a reduction in body fat may well boost running performance, cut down food intake too drastically and not only will training quality suffer, but the risk of illness and injury also increases dramatically.

Ron Maughan is professor of sport and exercise sciences at Loughborough University.

References

1. Journal of Sports Science 2004; 22:115-125

2. Journal of Sports Science 2004; 22;1-14

3. Journal of Sports Medicine 1986; 26:258-262

4. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 1990; 49:27A

5. Medicine and Science in Sports 1970; 2:93-95

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.