You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Achieve the impossible with the right mental approach!

Professor of Sports Psychology Andy Lane demonstrates how the seemingly impossible could actually be in your grasp – with the right mental approach...

On April 26th 2015 I ran 2.57:58 for the London Marathon. This isn’t an extraordinarily fast time, even for a 48-year old male. Nevertheless, achieving a sub 3-hour marathon took 24 years and multiple marathons to achieve. This article is about achieving goals, how our goals can conflict and through rectifying this conflict, and being mentally and physically prepared to work on the edge of your capacity, that success is attainable.Goal setting

Goal setting theory specifies that for goals to be motivating they should be specific, measureable, achievable, and realistic(1). As my goal-achievement took so long to achieve, it’s reasonable to ask whether setting a goal to run sub 3 hours was realistic in the first place! Goals should be motivating, inspiring, get you excited and make you nervous. However, excessively difficult goals can lead to anxiety and abandonment.Although my goal was ambitious, my analysis of the evidence suggests it was not unrealistic. In 1992, I had run a sub 60 minute 10-mile race, 1:20 half-marathon and competed in Olympic distance triathlons, performances that led me to be confident that running a sub-3 hour marathon was possible. This thought-process is common among many runners and of course, the first 16 miles are that pace are comfortable, but the final 10 miles are not.

In the first marathon, I went round the initial 13 miles in just under 1.30 and felt good. On course for a sub 3 at 20 miles, I experienced a wave of intense fatigue, which led to a slower pace, self-doubts and the final six miles taking well over an hour. So ended failed attempt number 1!

However, after that failure, I was confident that if I revised my pacing, thought about nutrition, and did more running in training, that a sub 3 was possible. Many times I would look back at that first marathon thinking ‘I only needed to complete 6 miles in 45 minutes’, and how it would indeed have been possible if I could have coped with the fatigue a little better. In retrospect, that was encouraging as studies show the importance of having positive expectations and remaining positive in successful sporting endeavours(2,3).

Life events changing goals

Not long after my first marathon, a sequence of lifestyle factors changed my priorities. In 1995 was son was born followed by my daughter in 1997. In 1995, I was offered an opportunity to do a funded PhD, a dream position, but it meant I took a massive drop in pay and to make ends meet, I did a great deal of extra lecturing. Over the course of two years my priorities had dramatically shifted.It’s appropriate of course to focus on raising your children, but my wife and I both ran and so from a couple who exercised regularly and supported each other, we became a couple that did not. This simultaneous change in goals meant that one partner was not encouraging the other as would normally happen during lapses in form, motivation, or injury episodes. Moreover, neither of us recognised the importance of providing social support – not ideal as research shows the value of one partner recognising when the other partner is in low mood and providing support(4).

Whilst I maintained regular exercise to the extent I would run most days, I went from someone who would enter races hoping to come close to PBs, to one who felt miserable at the slow times I was producing. Running did not improve my mood, but instead left me feeling frustrated and I would regulate this emotional reaction by focusing even harder on my work.

Over the next 12 years, I made multiple efforts to get back to running competitively and experienced a series of failures. I did the Sheffield marathon in 2000 and hobbled home; in 2002, I did the Wolverhampton marathon in over 4 hours, hobbling the last few miles in fatigue and self-loathing about how someone could end up performing so poorly.

Do your goals conflict?

Goal conflict occurs when efforts to pursue one goal negatively influences efforts to achieve another goal and can be a major cause of poor performance psychological distress. Sometimes it is easy to see that our goals conflict, at other times it not so easy(5). All behaviour is goal oriented but often we are not conscious of this fact. For example, eating might be driven by a goal of satiation, but at other times, eating might be driven by being part of a social function, such as dining out with friends.In my case, I was setting myself up to fail because I had numerous competing goals - work, exercise and my general health - which were in serious conflict. To make matters worse, I was not aware that my goals were in conflict, and the effect this was having. I entered races remembering the person I was in 1992. But that person was long gone and his goals and how he defined success were no longer helpful to me.

When people fail, it can lead intense emotions such as sadness, guilt and anger(6) and so it was with me. At over 90kgs which was 25kg heavier than in 1992, and some 30kgs heavier than my last boxing match in 1988, 3 months from my 40th birthday, I decided that things ought to change. I needed to decide what my goals were and do things differently, because doing the same thing was not working.

Sorting out goal conflict

The change was about prioritising goals, and saying to myself that sport related goals were important. At this point the sub 3 marathon goal was not uppermost in my thoughts, but I was committed to prioritising the time that was needed. I had goals that were horribly in conflict, and whilst I knew this deep down, I would justify my decisions accordingly.If you can recognise this situation, the first step is to identify your important goals. In my case, this process of reflection led to a decision that my diet had to change and I also began running with greater focus. Initially my goal was to sustain the habit of running by setting the goal to run for 10 minutes per day. Once back into the habit, I started trying to run faster.

My physical condition meant that my intervals were slow in comparison to my earlier years, but I did not make such a comparison and focused instead specifically on how I had performed in a previous session, in the previous week. This allowed me to feel and stay positive. In 2007, I ran the Tamworth 10km, finishing in just under 45 minutes, and felt fabulous. It was a hard run, struggling with fatigue from very early on in the run, but my time of 45 minutes for 10km became the stop gap time and a distance that I would later use for marathon running.

Sub 3 back on

My sub 3 marathon goal was reignited after taking part in an experiment for Professor Greg Whyte, where I ran a marathon around Hyde Park, London and had detailed cardiac screening before and after. The run felt easy and I did it around 3 hours 15 minutes, with just 2 week’s notice. Just as failure brought about feelings of misery, the joy of making progress, getting slimmer and getting faster was highly rewarding.By the time of Amsterdam Marathon in October 2008, I was under 70kgs, running half-marathons in 1.25 and confident - confidence that was built on successful performance and positive emotions because I was achieving my goals at a rapid rate. However, from Amsterdam in 2008 to London 2015, there were 12 marathon attempts. I managed 3 hour 2 minutes at Abingdon in 2014, reaching the athletics track finishing lap at 2.59.50, with 300m to go. I did Wolverhampton in 3 hours 3 in 2010, and after training well for Milton Keynes in 2012, was scuppered by atrocious weather.

The errors I made in 1992, were being repeated; that is, I was not focusing sufficiently on the mental and physical demands of what was needed - that is I was choosing to regulate pain by slowing and whilst this worked in the short term, of course, it meant the sub 3 hour goal slipped and negative emotion followed. Just like I needed to approach my diet differently, I needed to do the same for my training.

London 2015

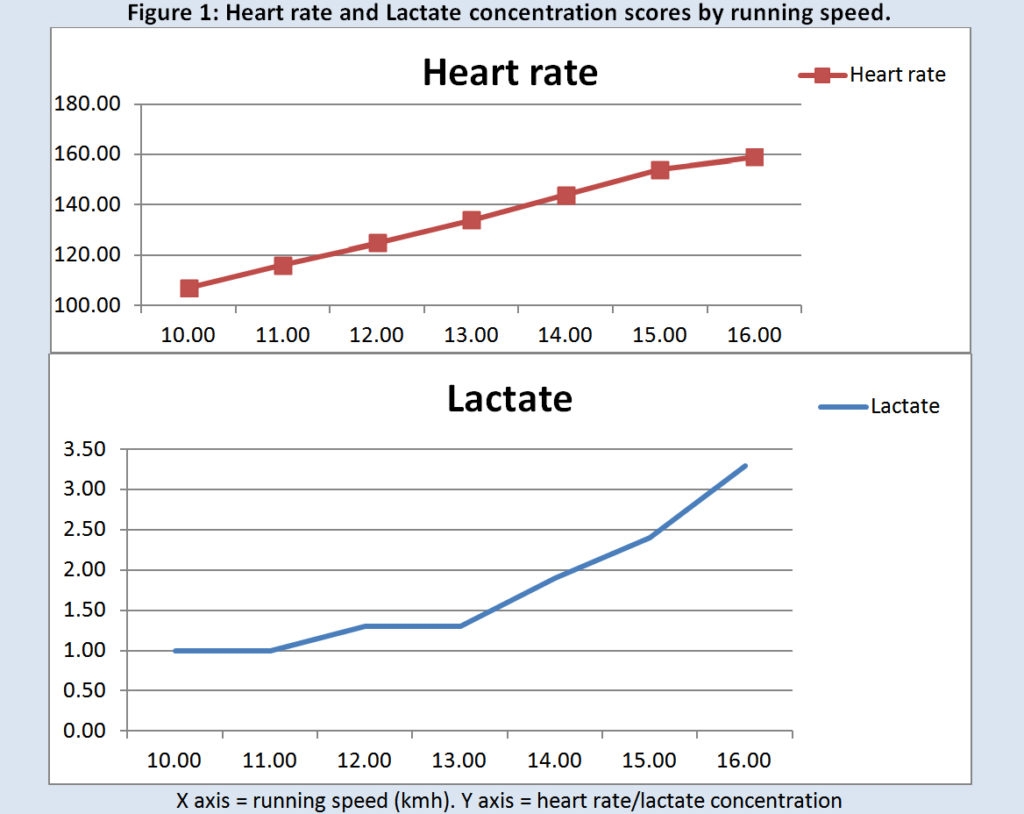

Training began for London on January 1st with the start of a 16-week plan. The importance of a plan is to make the training progressive, which builds confidence. For a marathon, the confidence to cope over the difficult part of the race is key. Following discussion with Professor Greg Whyte on training methods and sessions needed, I took a threshold test to assess my lactate concentrations during incremental increases in running speed. We started at 10kmh and increased speed every 3 minutes, taking lactate assessments and heart rate. The goal was to identify two key points (see figure 1):• - Lactate threshold (LT) - the speed at the LT is a strong predictor of the average speed that can be sustained in the marathon. The speed and heart rate at the LT are also useful in defining the transition between ‘easy’ and ‘steady’ running

• - Lactate turnpoint (LTP) - the speed at which there is a distinct sudden and sustained increase in lactate accumulation LTP tends to occur at around 1-2kmh above the LT (the difference is smaller in longer distance specialists and larger in middle-distance runners). LTP can also be used to define the transition between ‘steady’ and ‘threshold’ running”.

These results provided me with knowledge that my lactate threshold (LT) occurred at 13-14kmh within a heart rate range of 135-149 beats per minute. Training would be to do 60 to 150 minute runs at this heart rate intensity. The first few attempts at 60 minutes at lactate threshold felt difficult, partly because it was an awkward pace.

The approach was to prepare mentally for these sessions, and so I would experience thoughts such as “why not stop at 45 minutes?” My approach was to use imagery(6) to develop images of smooth running. The key triggers were to focus on my arms, and concentrate on moving these in rhythm as moving the arms in rhythm is much easier than moving the legs in rhythm as these are subject to the effects of fatigue and loading. In short, imagery was the psychological strategy I used to help me interpret and accept intense fatigue as an integral part of the process of achieving a sub 3-hour goal.

The mental approach was to be focus on achieving the goals set in training, which were determined via physiological parameters. This was recorded in a training dairy, made public via STRAVA which enabled further social support. Two 20-mile races were used the key long runs, with the goal to run at 3 hour marathon pace, which meant, that for both events, I needed to hold back. With both events the goal was set to run at threshold, keeping heart rate below the upper zone. The idea was to set a well-rehearsed pace, with a feeling that being able to run for further was possible.

Strength to the end

A key requirement for a marathon is mental strength over the last few miles. The growth of ‘Parkrun’ has provided people with many opportunities to run 5km, and I had previously completed many Parkruns before London. The message that ‘it’s only a Parkrun left’, combined with the experience of running faster than the required speed is one that was deep rooted and powerful.Of course, in a parkrun, you haven’t run 23 miles before starting! Therefore, my Parkrun training was revised so that I would do an extended warm-up and I used the parkrun as mental toughness training. The goal was to run as hard as possible for the entire run. The rationale was to produce fatigue that would signal the message in the brain to ‘stop or slow’ and then work with that signal to revise it to say ‘go and faster’.

The mental preparation would use imagery to recreate the tired feeling and then think through how to re-programme the internal voice. This is not an easy task as millions of years of evolution have produced a cardiovascular system and control mechanism that prevents you from running yourself to death!

My approach therefore was to break the task down - counting in 15 second units while running, as a means to build a rhythm. Each 15 seconds would represent an attempt to run faster - ie to do the opposite thing to what the brain is telling you! In reality, I didn’t run faster, but I did develop a strong sense of belief that when pain comes, I could respond positively. By setting the goal as to run and experience pain, I sought to welcome it as a friend from as early as possible.

The big day

For the run itself, there was good weather in that it was neither windy nor warm, both factors that affect my running. I was near the front of the ‘Good for age’ start, meaning I could run freely from the outset. The first 20 miles were a replication of the two 20-mile ‘races’ I had done, giving myself 45 minutes to run the final 10km. This was an intentional goal – I reminded myself of my Tamworth 10km time, and that if I could do it then, I could do it now.I talked myself through the penultimate 5km holding the required speed, before going into the final 5km, where my ‘pain training’ was triggered, and although a marathon is a different type of pain, the message to break the run down to short parts and hold a good rhythm were the messages in my mind. The difference between this marathon and many others was that I had planned my physical and mental processes to deal with the last parts.

In summary

If you are clear about the value of your goal, what it will take to reach that goal and the way in which you will need to manage competing goals, then you maximise your chance of success. Social support is vitally important as we share our successes and failures, and helping each other regulate our emotions is important. When it comes to marathon running, mental training to help cope with the sensations of fatigue can be vitally important. Using powerful positive messages from your training milestones can be invaluable in this respect.References

1. American psychologist, 2002; 579, 705-717

2. Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback 37, no. 4 (2012): 269-277

3. Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback 36, no. 3 (2011): 181-184

4. Psychology, 4,6A1, 25-33

5. Percep and Mot Skills, 2002; 94, 805-813

6. Psych of Sport and Exercise, 2015, 19, 1-9

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.