You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Mental overload: can it harm your quality of movement?

Using rowing as an example, SPB looks at new research on the link between cognitive demands during exercise and the effect on skill execution and movement quality

The indivisibility of mind and body has long been understood, and so it’s hardly surprising that the mind can and does have a big impact on physical performance. In a number of previous SPB articles, we have explored evidence showing that the brain is the master controller of the fatigue your muscles experience when performing exhaustive exercise. We’ve also seen how certain types of music can enhance performance and lower perceived effort levels(1,2), and even how different expectations of an exercise session can impact how much effort can be sustained(3).

Mental demand and sports performance

Given the powerful link connecting brain to exercise performance, it would be incredible if mental and psychological demands experienced by athletes didn’t affect performance, and this indeed is what we find. In a recent SPB article, Andrew Sheaff highlighted a recent review of all the research investigating whether performing resistance training while mentally fatigued would result in worse performance compared to performing exactly the same resistance training without prior mental fatigue(4). As Andrew explains, the results were very clear: the inclusion of mentally fatiguing activities prior to intense resistance exercise significantly reduced the number of repetitions subjects were able to achieve during a set. Indeed, the presence of mental fatigue, even in the absence of physical fatigue, negatively impacted performance.

In the study above, the impact of pre-existing mental fatigue on exercise was assessed. But what about the impact of mental demands during exercise itself – so-called ‘dual tasking’? The research on this topic is fairly unambiguous: adding extraneous cognitive loading (ie mental demands) during a motor task will typically lead to worse performance, as compared to normal or single-task conditions(5). Good examples of this include:

· Worse performance in soccer players who try to solve arithmetic problems while juggling a ball(6).

· Poorer time trial performance in cyclists asked to monitor multiple forms of feedback(7).

· Reduced accuracy, balance and smoothness when performing exercise requiring good motor coordination(8-10).

Coping mechanisms

How is it that performing mental tasks or being mentally fatigued while exercising affects physical performance? The most likely explanation stems from the fact that each of us has a limited capacity to attend to task-relevant stimuli. That explains why becoming mentally distracted – eg having an argument with your spouse while driving along the highway - is not recommended for safety! Even if your eyes never leave the road, the cognitive processing that results due to a mental distraction takes away from the processing required to execute the action of driving in the safest possible manner.

When extra cognitive demands do occur, research shows that humans adapt to that extra load by trying to free up attentional resources through alterations of behaviour. A very common way of accomplishing this is to reduce the quantity or complexity of ongoing motor execution(11). This effect is illustrated by the finding that healthy individuals walk with shorter stride lengths in dual-task conditions (ie when performing mental tasks), as compared to a single-task condition (ie just walking with no mental demands)(12).

Regression of movement patterns

Interestingly, this method of coping fits with the ‘progression-regression hypothesis’, where under adverse conditions, people tend to regress in their movement patterns in order to cope. To illustrate what this means, let’s take walking as an example. After years of progression and learning how to walk, our gait is typically characterized by long and confident strides. However, when we are stressed by increased cognitive demands, we tend to regress towards previously learnt patterns that involve less sophisticated movement patterns. In the case of walking, this means that we revert to the relatively short and less fluid steps that are typical of children learning how to walk (or an adult re-learning to walk after suffering from a stroke)(13).

Interestingly, anxiety-inducing stimuli ,which also divert attentional resources away from motor tasks (thus affecting movement patterns), can produce a similar effect. In golf for example, research shows that when players are in presence of an audience or facing the pressure of missing out on prize money and status rewards, movement patterns can regress to those seen in less experienced golfers. In this case, the regression is evidenced by shorter backswings or reduced follow-through) when putting(14,15).

Tighter coupling

Regression is one way of reducing movement complexity when facing cognitive demands, but another is via a phenomenon known as ‘tight coupling’. In tight-coupling, movements in different limbs tend to take place simultaneously, which reduces movement complexity(16). Because tightly coupled movements are less complex and easier to learn, it’s a common observation that when athletes take up a sport and develop specific sports skills, the movement patterns tend to start in a tightly coupled manner and become progressively uncoupled as the skill level increases.

Taking rowing as an example, the ideal (uncoupled) rowing action sequence usually progresses from proximal (near the body center) to distal (away from the body center) areas. This allows the larger muscles (the glutes, and the quadriceps) near the body center to initiate the rowing action, resulting in effective power development(17). However, novice rowers typically employ a more tightly coupled movement, extending their legs and pulling the oar at the same time (until the stoke technique is mastered). Following skill practice, athletes in general typically progress from tight coupling to a more uncoupled action, which allows more nuanced and sports-specific movement.

Figure 1: Ideal rowing technique

Pressure and coupling

Interestingly, when athletes face task-related stress or pressure (for example, competing for a prize or title, or in front of an audience), they may revert to a tighter coupling between body segments – ie skill levels regress. In a 2017 study, experienced basketball players were asked to shoot free throws in normal practice sessions (ie with no added pressure) or under ‘stressful’ conditions(18). In the stress condition, participants were told that a video camera was filming their shots, that the recordings would be analyzed by an expert later, and that they were competing with others for prize money. Under this stress, participants demonstrated greater coupling between peak velocities in their knee and elbow, as compared to throwing under normal circumstances. As alluded to above, this phenomenon seems to align with the progression-regression hypothesis: ie when under pressure, athletes’ movement patterns regress and became more ‘novice-like’!

Do highly trained athletes regress?

At this point, you might be wondering if this ‘regression’ under stress or cognitive demand phenomenon affects highly trained athletes. The theory here is that with years and years of training and practice behind them, the motor actions have been repeated so often that they may become automated to the point where elite athletes can pay relatively little attention to the motor task at hand, and therefore have plenty of spare capacity for extraneous cognitive tasks, or to complete under stress(19).

Some studies on athletes with many years of competitive experience behind them suggest that regression may not occur when elite athletes face cognitive demands. Research on highly experienced golfers did not observe regression(20), neither did research on basketball players with over 15 years’ of experience in competition(21). However, there’s still much uncertainty because the studies that have found no regression used relatively simple cognitive tasks (ie imposed little mental demand upon the athletes). In addition, they measured the impact on relatively simple tasks, and perhaps most notably, they did not assess whether the athletes’ kinematics (movement patterns) changed in any way. Finally, research on expert or elite athletes is relatively scarce; many studies that claimed to have recruited elite athletes actually involved participants who were not competing at anywhere near the highest level in their sport. In reality then, very little is known about how cognitive load affects athletes who most depend on exquisite levels motor performance - ie true professionals or elite athletes.

Answers from rowers

To try and reach a definitive conclusion, a team of Norwegian sports scientists has investigated the impact of cognitive loading on ‘regression’ and ‘coupling’ in elite and amateur rowers(22). Published last month in the journal ‘Human Movement Science’, the goal of the study was to compare elite and non-elite rowers to see how cognitive demands during rowing impacted the movement patterns – ie did they regress or become more coupled? The researchers surmised that because the elite rowers were so practiced in their skills, they would be less or unaffected by cognitive demands imposed on them - but that the amateur rowers would be significantly impacted.

What they did

Eighteen male rowers - nine elite and nine non-elite - participated in this study. The elite rowers were members of Team Norway, the highest-level training group in the Norwegian national team system, preparing for the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo (ie very elite!). The non-elite rowers meanwhile were a group of lower-level rowers, with an average of just over four years’ rowing experience. These non-elite rowers were recruited based on the condition of never having won a major national or international competition as an individual rower, and never having represented the Norwegian national rowing team. All the rowers performed four separate trials on four separate occasions:

· Rowing at 75% of their expected 2,000m racing pace (low physical load) while performing mental arithmetic (cognitive loading).

· Rowing at 75% of their expected 2,000m racing pace (low physical load) without any mental arithmetic tasks (ie no cognitive loading).

· Rowing at 85% of their expected 2,000m racing pace (high physical load) while performing mental arithmetic (cognitive loading).

· Rowing at 85% of their expected 2,000m racing pace (high physical load) without any mental arithmetic tasks (ie no cognitive loading).

The rowing trials were conducted on a rowing ergometer, but one that permitted a much more dynamic movement (ie less constrained), and which therefore better resembled on-water rowing in terms of actual movement mechanics compared to (more conventional) static rowing ergometers. In the cognitive loading trials, arithmetic problems were presented via loudspeakers, and participants had approximately 10 seconds to respond verbally before the next problem was presented. The arithmetic problems consisted of either the addition of single and double digit numbers or the multiplication of single and double digit numbers.

What was measured

In addition to data on stroke lengths, stroke-by-stroke measures of rowing speed were assessed throughout all of the trials. Most importantly however, movement patterns were also analyzed using a sophisticated motion capture system with 11 infrared cameras was used to explore rowers’ kinematics. Reflective markers were attached to bony prominences on the rowers’ shoulders and hips, and also on the ergometer handle, on the side of the seat (which on this ergometer was able to move around to better replicate on-water rowing). Figure 2 shows what the motion capture system looked like in use. The goal of this motion capture was to observe how much the movement patterns deviated from the ideal movement sequence described above.

Figure 2: Motion capture system in action

Related Files

Numbers indicate the location of the (1) ergometer monitor, (2) frontal part of the rowing ergometer, which moves horizontally as a function of the rower’s leg extension/flexion, (3) ergometer handle, (4) shoulder marker, (5) hip marker, and (6) marker on the side of the seat, which moves vertically as a function of seat stability.

What they found

The researchers predicted that when there was no cognitive loading they would observe greater decoupling between leg extension and trunk extension during the drive phase and recovery phases, longer stroke lengths and greater smoothness – but only in the non-elite rowers. In the elite rowers, the expectation was that their highly developed and automatic execution of skills would make them reasonably immune to cognitive demands during rowing. But what did they actually find?

The key results were as follows:

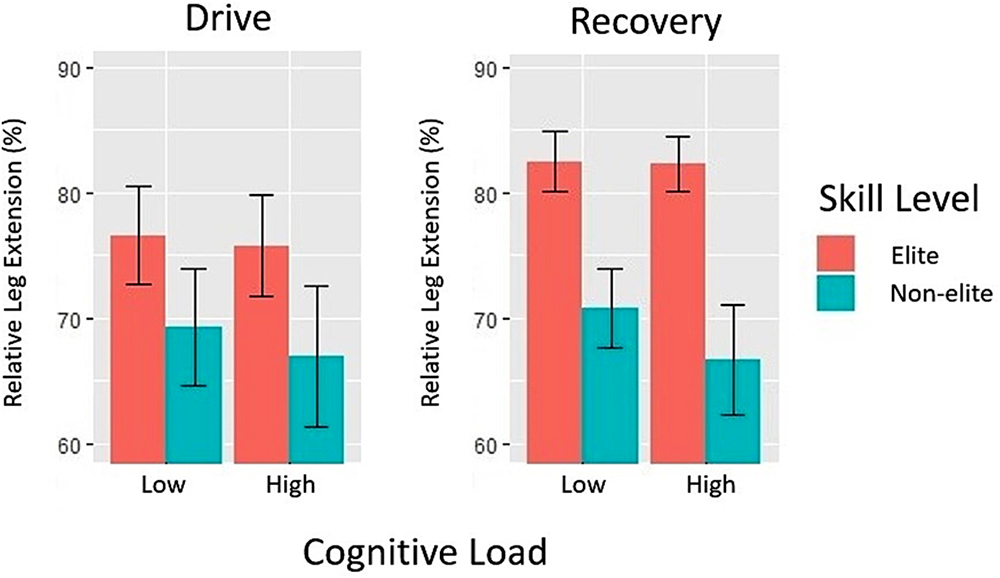

· Going from low-cognitive load rowing to high-load rowing led participants to demonstrate less leg extension before the trunk rotated during both the drive and recovery phases of the rowing cycle. This reduced leg extension resulted shorter stroke lengths (see figure 3).

· The overall technical execution became more compressed (ie tighter coupling) under high cognitive load.

· There was less motion smoothness under increased cognitive demands (ie regression had occurred).

· These results were observed in both the elite and non-elite rowers – ie the highly developed rowing skills in the elite rowers did NOT make them immune to the extra cognitive demands.

In a nutshell, the general theory that having highly developed and practiced skills makes elite athletes much more immune to the effects of cognitive overload was thrown into question by this data!

Figure 3: Leg extension (stroke length) in drive and recovery phases of the rowing stroke

Why is it that the highly developed and automatic skills that characterize elite athletes could be just as susceptible to cognitive demand as the less automatic skills of non-elite athletes? The most likely explanation is that although the rowing skills in elite rowers are more highly developed and practiced, they are by no means ‘automatic’. When it comes to skill execution, it seems that elite athletes still need to devote sufficient cognitive resources to attentional detail (cues from the environment and the athlete’s own feedback) in order to maintain performance(23). If too much cognitive distraction occurs, the attention to the task at hand suffers and performance drops.

Implications for athletes

What these results demonstrate is that contrary to popular belief, when extraneous cognitive demands are increased during sport, skills and movement pattern execution are adversely affected. Importantly, this seems to be the case regardless of your level of expertise or how well developed those skills are. In terms of practical implications, this means that athletes of all levels need to minimize extraneous cognitive demands when seeking optimum performance or practicing and honing their skills.

Note that cognitive loading doesn’t necessarily mean arithmetical problem solving; thinking about a problem at work or college, worrying about exams, worrying about the situation at home with your family or loved one, worrying about money and finances can all take up valuable cognitive processing power and reduce your attention to the task at hand. Of course, we can’t always prevent these life challenges, but by being aware of their impact on performance, we can better manage them.

Here then are some practical tips (for athletes at all ability levels):

· Don’t let your focus drift and start thinking about problems (of any sort) during important training sessions or competition; stay focussed on the quality of your movement and getting the job done as well as possible.

· Be flexible in your scheduling; save skill practice/development session for times when you are mentally fresh and have a clear head.

· Try not to schedule important races or competitions during mentally demanding periods such as job or house moves, exams etc.

· Be careful when using electronic feedback (eg bike and running computers) during training sessions and competition; research suggests that by increasing cognitive demand, excessive feedback and data can actually harm your performance.

· Practice on developing your attentional focus and eliminating distractions during competition. An excellent way to do this is via ‘mindfulness training’ – see this excellent article by Alicia Filley.

References

1. Percept & Motor Skills 83, 1347-1352, 1996

2. J of Sport Behavior 20, 54-68, 1997

3. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2018 May;58(5):744-749

4. Motor Control. 2022 Dec 12;27(2):442-461

5. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 (4) (2021), p. 1732

6. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61 (2) (2020), pp. 168-176

7. Front Psychol. 2020 Dec 23;11:608426. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.608426. eCollection 2020

8. Journal of Motor Behavior, 52 (2) (2020), pp. 204-213

9. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36 (5) (2018), pp. 513-521

10. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 117 (2) (2013), pp. 411-426

11. Human Movement Science, 21 (5) (2002), pp. 831-846

12. Cogent Psychology, 4 (1) (2017), p. 1372872

13. Journal of Physiotherapy, 61 (1) (2015), pp. 10-15

14. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 81 (4) (2010), pp. 416-424

15. International Journal of Sport and Health Science, 8 (2010), pp. 83-94

16. Frontiers in Psychology, 11 (2020), p. 1295

17. Proximal-to-distal sequencing behavior and motor cortex. F. Danion, M. Latash (Eds.), Motor control: Theories, experiments, and applications, Oxford University Press (2010), pp. 159-176

18. Effects of pressure and free throw routine on basketball kinematics and sport performance. Arizona State University 2017. keep.lib.asu.edu/_flysystem/fedora/c7/178656/Orn_asu_0010N_16755.pdf

19. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 8 (1) (2015), pp. 106-124

20. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 8 (1) (2015), pp. 106-124

21. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 10 (1) (2004), pp. 42-54

22. Human Movement Science Volume 90, August 2023, 103113

23. Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory Emotion, 7 (2) (2007), pp. 336-353

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.