Cryotherapy - can you freeze your way to recovery?

Alicia Filley asks whether cryotherapy is beneficial for post exercise recovery, or just a cool trend?

During the height of the competition season and periods of intense training, there’s little time for proper recovery. Many athletes may participate in a number of races in a relatively short time period. As such, any method that improves recovery and lessens the effects of exercise-induced muscle damage (EIMD) can benefit athletes.

Cold therapy, used since ancient times to combat the pain, swelling, and stiffness from intense activity, remains the cornerstone of training room treatment modalities. Methods include cold-water immersion (CWI), ice massage, and ice packs. In the late 1970s, the Japanese introduced a new type of whole-body cold application using cooled air. Originally designed for use with arthritic patients, Polish developers took the idea, improved the technology, and developed protocols for healthy individuals. Two delivery methods exist for this type of cryotherapy (also called cryostimulation): partial-body cryotherapy (PBC) and whole-body cryotherapy (WBC).

In PBC, an individual steps into a cylindrical chamber wearing booties and a bathing suit, with their head and hands sticking out of the top of the chamber (see figure 1). If hands remain in the chamber, they must be covered. Liquid nitrogen provides the cooling vapour which surrounds the subject in the chamber. Sensors measure the temperature at the nitrogen outlet and usually report it between -110°C and -140°C (although there is no way to verify that the temperature reported is the temperature experienced by the individual inside). As for the circulating nitrogen, the heaviness of the very cold vapour means most of it remains toward the bottom of the compartment.

Figure 1: Partial body cryotherapy (PBC)

Doctoral candidate Erich Hohenauer monitors a study subject in a partial-body cryotherapy chamber(1) (used with permission).

Manufacturers report no adverse effects from this level of nitrogen inhalation. Despite needing a tank of liquid nitrogen, PBC units are portable, and therefore can be utilised at sporting venues without a permanent installation. Cryo-spas in the United States often refer to this type of treatment as WBC. However, WBC differs in the methodology of cold air delivery.

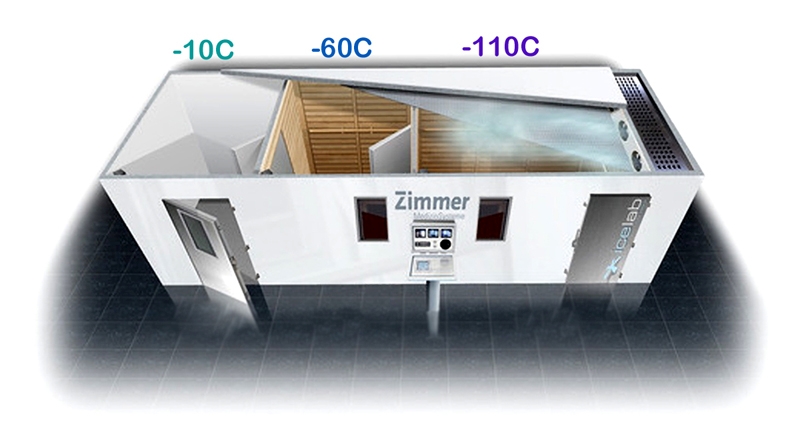

The alternative method of cooling, known as WBC, consists of a main chamber and one or more antechambers (see figure 2). To cool the air in the rooms, refrigerants, such as liquid nitrogen, flow through pipes located inside the walls, or compressor units act as super air conditioners. The subjects never come in direct contact with the cooling agent. The rooms hold two or more people who also wear minimal clothing but must don coverings to feet, hands, mouth/nose, and ears. The antechambers allow acclimatisation to the cold and individuals spend at least 30 seconds in the outer room (usually cooled to -60° C) before entering the main compartment where the air temperature drops to -110°C to -140°C for two to four minutes.

Figure 2: Schematic of the Zimmer Icelab(2)

With appropriate covering including a breathing mask, subjects spend 30 seconds acclimating in each antechamber followed by one to three minutes in the main cooling room, where the temperature is held at around -110C.

Both methods require an attendant present to monitor subjects in the chamber. Individuals may exit the chamber at any time. Before entering, subjects must be completely dry or else risk frostbite. Many medical conditions prohibit the use of such a modality (see table 1). For healthy individuals, cryotherapy is deemed completely safe. However, in 2016 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a statement of caution, reminding consumers that the industry is not regulated(3). For this reason, and citing the death of a cryo-spa worker in 2015, the agency advised against the use of cryotherapy. The cryo-spa employee misused the equipment by entering a chamber without an attendant, with fatal consequences(4).

Table 1: Medical conditions that prohibit the use of partial-body, or whole-body cryotherapy

| Cold intolerance | Peripheral vascular disease | Nerve injury | Learning disability/debilitating mental disorder | Heart attack/Coronary artery disease |

| Cardiac pacemaker | Severe hypertension | Diabetes | Pregnancy | Claustrophobia |

| Raynaud’s syndrome | Blood clot | Cryoglobulinemia | Unstable angina or chest pain | Arrhythmia |

| Bleeding disorder | Cancer | Hypothyroidism | Fever/infection | Respiratory disorder |

| Heart failure | Severe thinness |

Ice, ice, baby

Most sports scientists believe EIMD occurs as a result of eccentric contractions – those activities that load the muscle in a lengthened position – for example, downhill running. The smaller components within the muscle known as the myofilaments, stretch, while trying to maintain their bonds. After repeated eccentric contractions, these myofilaments may overstretch and ‘break’.Damage occurs on a cellular level within the muscle, and a sequence of events begins that includes the release of muscle protein into the blood stream, calcium into the cells, and an inflammatory response. With EIMD the athlete typically experiences swelling, pain, strength deficits, and limited range of motion. While these effects might not be felt until 24 to 48 hours after the activity, the inflammatory cascade begins immediately after the damage occurs.

Theoretically, WBC/PBC interrupts this cycle through the constriction of surface blood vessels. This constriction purports to reduce the amount of pro-inflammatory markers in the blood, and thus limit muscle damage. The ability of WBC to interrupt or modulate the inflammatory response remains uncertain. However, WBC appears to effectively increase the number of anti-inflammatory compounds, compared to controls, which produces an overall anti-inflammatory effect(5).

Cool customer

With the cost to consumers at anywhere from £35.00 to £100.00 per session, is WBC or PBC superior to other traditional methods of cooling? Researchers at Liverpool John Moores University compared the effect of CWI to WBC on tissue temperature and blood flow in the legs after exercising on a stationary bike(6). In a randomised, crossover design, ten males cycled, then experienced either cold-water immersion (CWI) for ten minutes min at 8°C or WBC at -110°C for two minutes. The results showed greater vasoconstriction and cooling with CWI than WBC - even to deep thigh muscles.In a well designed study at the London Sports Institute, scientists randomly assigned 31 endurance-trained male athletes to a WBC, CWI, or placebo group, before completing a regulation length marathon(7). After the race, the WBC group received two cryotherapy sessions: the first for three minutes at -85°C, followed by a 15-minute thaw, and then another four-minute session, also at -85°C. The CWI group sat in an ice bath chilled to 8°C for 10 minutes. The placebo group ingested what they thought was a tart cherry juice supplement (known for decreasing inflammation and improving recovery) for eight days (including race day). However, in reality, the supplement was a sham.

Researchers collected post-intervention measures at 24 and 48 hours after the intervention. Quadriceps strength, when compared to baseline, was better in the CWI and placebo group than the WBC group. Neither cryotherapy method showed significant influence on inflammatory markers when compared to placebo. However, participants felt WBC relieved their post exercise symptoms better than CWI or placebo.

In fact, the whole body cryotherapy showed such disappointing results when compared to placebo, the investigators in this study went so far as to label the cryotherapy methods as ‘harmful to muscle strength’. Both therapies increased the levels of circulating muscle proteins as well, suggesting that cold intervention adds to muscle trauma. Of note, both cryotherapies were roughly 20°C warmer than typical protocols.

Swiss scientists compared partial body cryotherapy (PBC) to CWI by randomly assigning 19 healthy active males to either intervention after five sets of 20 box jumps (to induce muscle damage)(1). The subjects then received two and a half minutes of PWB at -135°C or spent 10 minutes in a CWI tub at 10°C. Physiological measures of muscle oxygen saturation, blood pressure, skin temperature, and circulation, collected in 10-minute intervals for one hour after the intervention, were significantly better in the CWI group. Recovery measures of soreness, swelling, maximal muscle contraction, and vertical jump performance, showed no appreciable difference between the interventions. The authors concluded that CWI was more effective at improving physiological factors after damage-inducing exercise than PBC.

Stone cold facts

When it comes to gaining a performance edge, famous athletes and even whole athletic teams, have jumped quickly on the cryotherapy bandwagon. And why not? It was touted as an effective and familiar modality. Perhaps cold air could be a better delivery system than cold water (used in CWI). However, physics says otherwise; water conducts heat better than air. In other words, cold water extracts more heat from the body than cold air. Direct skin contact with an ice pack is even better.Still, the internet and the locker room brim with anecdotal stories of WBC or PBC being the secret to a faster recovery, less pain, and general feelings of well being. In regards to the first claim, there does appear to be a boost in levels of anti-inflammatory components in the blood stream after even one session of WBC. However, the magnitude of this boost is not significantly better than traditional CWI, which both cools and constricts lower limb blood flow more effectively.

Secondly, participants report better pain relief with WBC than using nothing, but not significantly better than with CWI. The subjective measures of pain, while valid, do not discount the placebo effect. As for mood elevation and feelings of well being, WBC appears to have the advantage over CWI. Subjects describe feeling tingly, energised, completely relaxed, and euphoric after WBC. Some users even liken the feeling to the ‘afterglow’ from sex!

Evidence shows a session of WBC releases noradrenaline, a neurotransmitter that modulates pain sensation, and other hormones such as ß-endorphins(8). No doubt, the release of noradrenalin and hormones contributes to these post-WBC feelings. Researchers caution however that as subjects acclimate to repeated WBC, the hormone release (although not the noradrenalin rush) lessens with consecutive treatments(8). Whether WBC interrupts the inflammatory cycle and therefore decreases pain, or the sensation of pain lessens as the feelings of well being improve, has yet to be determined.

What about performance? That is, after all, the ultimate goal - to recover quickly and perform just as well, if not better, the next go-round. The few studies that have looked at post-WBC function compared to a control (ie no post-exercise cooling at all) report better results with WBC. Nut once again - when compared with traditional CWI, WBC didn’t result in a significant improvement in performance. One study even labelled cryotherapy as detrimental to muscle function compared to placebo.

Cold hard cash

The decision to incorporate WBC into your recovery plan comes down to affordability in both time and money. If you are medically healthy and want to feel like you are riding the latest trends in sports performance, then the only cautions for WBC are the lack of standardisation and regulation in both protocol and delivery; absence of proof of actual in-cabin temperature; and dearth of knowledge on the long-term effects. If you decide to try this method, for best results make sure the session takes place within 24 hours of exercise. Before you spend your money, however, examine if you are maximising the other proven facilitators of recovery: CWI, nutrition, hydration, periodisation, and sleep.Case study: Cristiano Ronaldo

Real Madrid forward Cristiano Ronaldo attributes his football prowess and longevity in the game to using PBC as part of his recovery routine. The Portuguese footballer first received PBC as a treatment modality for an injury, and soon found himself hooked on the twice weekly sessions. So much so, that in 2013 he famously had a PBC tank installed in his home outside Madrid at a cost of (at that time) roughly £36,000.

His current routine is a cold ‘dip’ two times a week for two to three minutes at a time. No one can argue that the 33-year-old keeps up with the youngsters with 37 goals scored thus far this season, according to the Real Madrid website(9). Whether it’s the regular PBC, sports experience, or intensive training that enabled him to recently score his 50th career hat-trick, he’s found a formula that works.

References

-

Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;1–11

-

zimmerusa.com/products/cryo-therapy/icelab/inside-icelab/

-

www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm508739.htm

-

www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2015/10/26/salon-worker-praised-cryotherapy-then-froze-to-death-during-treatment/?utm_term=.aa4f942d8a11

-

Front Physio. 2017 May;8:258

-

Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017 Jun;49(6):1252-1260

-

Eur J Appl Physiol. 2018;118:153-63

-

J Therm Biol. 2016;61:67-81

-

www.realmadrid.com/en/football/squad/cristiano-ronaldo-dos-santos#playerinfo

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Further reading

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.