L-carnitine: back on the block

Once promoted as a ‘fat burner’ and endurance enhancer, the supplement L-carnitine has fallen out of favour in recent years. But as Joe Beer explains, new evidence suggests that we may have been too quick to dismiss its ergogenic properties...

This article:

- Explains the role of carnitine in exercise

- Looks at recent finding on carnitine and performance and explains why previous research failed to find benefits

- Provides practical information for athletes wishing to use carnitine for themselves

Carnitine (more formally known as 3-hydroxy-4-N,N,N-trimethylaminobutyric acid) is a naturally occurring amino acid compound whose structure is related to B-group vitamins. Over 90% of your body’s carnitine content resides within the muscles; hence, it’s not surprising that dietary sources high in content are meats such as beef, steak and lamb. Carnitine can also be synthesised from two other amino acids - lysine and methionine.

How does carnitine work in the body?

Carnitine has previously attracted the attention of scientists because it has two very important functions that help regulate energy use:- It assists the movement of fats across membranes within your muscle mitochondria (the energy factories that power muscle cells) for both aerobic energy production, and recovery between anaerobic efforts. Muscle carnitine allows the one-way process of shuttling fatty acids into the furnace. However, how quickly this happens depends on carnitine availability inside the muscle. This function explains the ‘fat burning’ tag, and has been seen by many as the biggest reason to research and ultimately use carnitine supplements. The logic goes that if you can get more carnitine to do its job properly, then fat use during rest and exercise can go up, saving precious stores of muscle glycogen (the body’s preferred fuel during hard exercise) and prolonging endurance

- During sudden changes in energy requirement by muscles – eg changes of pace or when beginning exercise - the carnitine in the muscles can assist by helping to control the build up of a substance called acetyl-CoA by forming acetyl carnitine. This so-called ‘buffering’ capacity in the muscles provided by carnitine can help reduce lactate accumulation, which can result if acetyl-CoA concentrations continues to rise during high intensity exercise. The overall result is less fatigue.

The early days

Once identified by researchers, doctors or technologists, many natural compounds soon attract the attention of athletes and coaches, keen to see if they can help performances and medal tallies. In the early part of the 20th century, carnitine was an emerging compound, having been discovered in muscle in 1905(1). However, it wasn’t until the 1950s that research showed carnitine bound to fats enabled them to enter the mitochondria, and thus was a key factor in muscle fat use (see box 1).Ironically, carnitine had a very problematic period in sports science research for the next five decades. While it enjoyed increasing medical use, particularly in patients with certain heart conditions, scientists and early adopters in sport were less impressed.

Many reasoned that if it could save muscle glycogen and increase fat burning, it should be useful for athletes. But this was based on conjecture rather than solid science, and evidence of a performance-enhancing effect at this stage was zero. However, this didn’t prevent huge marketing efforts by supplement companies and massive increases in sales!

In hindsight most users who took carnitine during the 80s, 90s and early 2000s had been wasting their money - a fact become apparent when we look at recent studies on carnitine. Despite this some coaches and elite triathletes reported positive effects. Indeed, I myself – working with elite triathletes such as Alan Ingarfield (at the time one of the fastest UK Ironman athletes in his age group) - believed that carnitine could enhance performance and in 1993, I suggested it helped athletes in several ways, including increased fat metabolism and faster recovery(2). In hindsight we may have got good results because of a very slight (and accidental!) tweak in how we used it, but one that had big ramifications.

A new approach

It took over two decades to see the potential of carnitine – all thanks to a research group based in Nottingham, UK who looked at the problem differently(3). They recognised that simply supplementing carnitine failed to show a gain in muscle stores(4). However, they wondered if a similar supplementation approach shown to be effective in raising muscle stores of creatine – ‘pushing it in’ using carbohydrate to help the process along – could also work with carnitine(5).This led them to test eight subjects using intravenous infusion insulin (the hormone released when carbohydrate is consumed) and also carnitine infusion to similarly raise blood-carnitine levels above that observed when eating dietary sources of carnitine. The results showed that an infusion of carnitine, while it boosted blood carnitine, failed to raise muscle stores over a 5-hour period. However, the ground breaking finding was that a simultaneous infusion of insulin and carnitine did raise muscle carnitine levels - by 13-29%(3). In plain English, the insulin seemed to have removed the barrier to carnitine uptake and there was now a way of manipulating muscle carnitine levels; ie by co-ingesting carnitine with carbohydrate (to produce an insulin spike).

This finding went against the prevailing assumption that you should use carnitine in a fasted state and away from meals to promote fat burning. And while anecdotal, it also helped to explain how we had observed benefits back in the 1990s; we had supplemented high levels of carnitine with high-carbohydrate meals, which raised insulin, promoting a carnitine-loading effect.

These results also help to explain why the odd study had shown positive benefits of carnitine supplementation. For example, an earlier paper published in 2002 on resistance training in men gave very explicit methods of carnitine use(6). Subjects received written instructions to consume two 500mg capsules of carnitine with breakfast and lunch – making a total dose of 2 grams per day. Eating breakfast or lunch (containing carbohydrate) when consuming carnitine would have stimulated insulin and helped elevate muscle carnitine, and researchers observed that carnitine users had 41-45% better muscle recovery from high intensity squat exercises. Sadly however, muscle carnitine content was not actually measured.

Carbohydrate connection

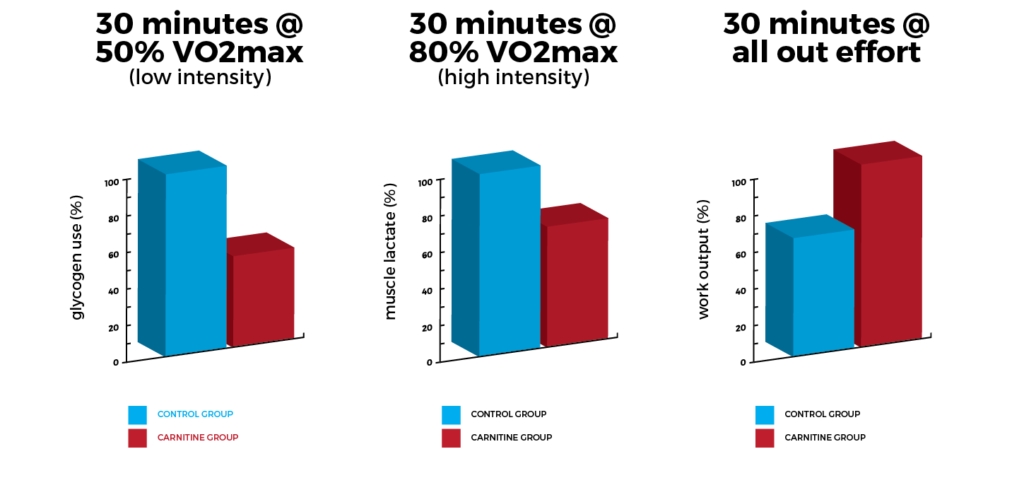

The theory (of carbohydrate intake enhancing carnitine uptake into muscles) is all very well, but it’s no substitute for scientific testing, so with that in mind, the Nottingham research group then looked at the conventional oral use of carbohydrate (to produce a natural insulin spike) combined with carnitine ingestion, to try to raise muscle stores. Importantly, they also measured physical performance too(7).For 168 days, subjects drank a sports drink containing 80g of carbohydrate, with and without 2000mg of carnitine, twice a day. At 12 weeks no muscle carnitine differences were apparent between the groups. However by 24 weeks, carnitine users had increased muscle stores by 21% (see figure 1). But there were performance benefits too (see figure 2):

- During 30 minutes of exercise at 50% VO2max (mild intensity), the carnitine group were using 50% less glycogen during exercise (ie more from fat oxidation) by the 24th week of loading compared to the control group;

- When exercise intensity was increased to 80%VO2max (hard) for a further 30 minutes, the carnitine group users had muscle lactate levels that were 44% lower than the controls.(25 vs. 44 mmol/kg dry muscle);

- During a final 30-minute all-out effort, the carnitine users sustained a 35% greater workload than the control group who did not supplement carnitine!

Figure 1: Carnitine accumulation in muscles

Compared to controls, the carbohydrate + carnitine group increased muscle carnitine levels by 24%

Figure 2: Carnitine and performance

A comparison of carnitine and non-carnitine users (control group): shows the glycogen used at 50% VO2max, lactate accumulation at 80% VO2max, and work output during a 30-minute all out effort

You might think that research showing muscle carnitine levels can be raised, muscle glycogen spared and lactate levels suppressed to increased muscle work ability would generate a huge amount of follow-up interest in the wider press, but it hasn’t. This is despite the fact that as recently as 2013, research found that just three months of twice-daily carnitine and carbohydrate supplementation (80g carbs + 1.5g carnitine) was not only able to raise muscle carnitine levels significantly, but also increase the activity of genes in the muscles that are involved in stimulating fat burning during exercise(8). Indeed, reading this, you are still in a small minority of athletes who are aware of the potential benefits that carnitine appears to offer when used in a particular manner.

Carnitine user case study, Chris Goodfellow - triathlete with 8h 47mins PB for the Ironman event

Although carnitine has previously been dismissed by many researchers as an ergogenic nutrient, its use in the manner described above (ie with carbohydrate) has found favour with a small number of elite endurance athletes. While these positive reports can only be considered as anecdotal evidence, the recent science is beginning to lend credence to carnitine’s use. As Chris explains: “I first started using L-Carnitine in 2011/2012.This coincided with a big step up in Ironman performance from top ten age-group athlete to top ten overall in big Ironman races. More recently, I started using L-Carnitine again this November (2015). This also coincided with a significant drop in heart rate at a specific cycling power and cadence. While I am not suggesting carnitine is the sole reason for these improvements, I do believe it plays a significant role.”

Practical guide to using carnitine

The first thing to say here is that while the recent research has been conducted in a scientifically rigorous manner, it’s still early days and more research is needed before we can be entirely confident about the benefits of carnitine + carbohydrate supplementation. Having said that, carnitine is relatively cheap and safe, so there are few drawbacks to trying it.If you’re tempted to give carnitine supplementation a try, the clear message from the recent science is as follows: carnitine should not be taken on its own just before present exercise; it needs instead to be taken along with a high carbohydrate intake to help ‘push’ it into the muscle for future exercise sessions! Bearing that in mind, here are some practical guidelines for its use:

-Where can I buy it and in what form? - For sports performance, the ‘L-carnitine’ version is adequate and readily available at health food stores and online. The issue to consider is that athlete in many sports have to ensure they abide by NGB rules (eg. triathlon, cycling, running, swimming etc) You should really source from a manufacturer that produces a lab certified product – check www.informed-sport.com. However the governing body WADA does not test and endorse supplements; it only produces a list of banned substances. The majority of studies into athlete use have been with L-carnitine or L-carnitine tartrate, and they can be considered the same in terms of efficacy.

-How to should I use carnitine with everyday meals? - The most important aspect of the recent carnitine research (and the accidental outcome of the early testing with athletes) is the consumption of a high carbohydrate source at the same time. Research has used 80g of simple sugars to great effect, and this could be duplicated with a sports carbohydrate drink powder or other quick-releasing confectionary or foodstuffs. Conversely, other studies have found positive benefits with normal breakfast or lunch scenarios. I would therefore suggest the following options:

- High-carbohydrate sports drink/sports nutrition options: this is the best way to exactly replicate the research, but it does mean a high dose of simple sugars. Some athletes will therefore train on zero carbs and then have this carbohydrate dose as a recovery drink, plus consume 1500-2000mg of carnitine (eg 80g sports drink polymer + 500ml water + 2000mg carnitine. Note that recent research suggests carbohydrate and protein mixtures may be ineffective agents for carnitine loading(9). However, this could just be that the carb/protein dose was 40g/40g, and a more carbohydrate-loaded formula is better (eg 60g+25g).

- High-carbohydrate breakfast options: this is an easy way to get 80g of carbohydrate using normal foods, though you have to calculate the carbohydrate total as serving sizes, and remember that carbohydrate content varies. While it might contain some simple sugars, it allows a ‘real’ morning or midday meal to be eaten while supplementing carnitine. Examples include cereal containing 60g of carbohydrate + ½ chopped banana + milk; 2 slices of toast and jam or honey + orange juice.

- High-carbohydrate midday options: as studies often use twice-a-day loading, it may be that some days both doses are with meals, whilst other days, one is with a meal and another is with carb drink after training. Midday options could include rice cakes with chutney + banana + fruit juice; bread sandwiches with salad and small amount of chicken + fruit salad.

- Creatine Monohydrate: normally creatine is loaded into muscle with a 5g dose with foods, or a small carbohydrate snack. The carbohydrate can increase the amount of creatine being up-taken by muscle. Adding 5g creatine to 2-3g of carnitine, together with carbohydrate should assist in loading of both nutrients.

- Carbo-loading/phasing: if an athlete is carbohydrate loading or having low and high-carbohydrate periods in their day and training week, the times when carbohydrates are ingested (such as a high-carb recovery meal after a long session) are ideal times to include the 1500-3000mg of carnitine. As an effective (80g) carbohydrate dose is only 320 calories of carbohydrate, this is likely to be used in just 40-60 minutes of endurance exercise, so can easily be managed within a calorie plan for the athlete’s whole day.

References

-

J Physiol 1905; 581(2),431–444

-

Beer, J. (1993) ‘Fats show business’. Two Twenty magazine. February issue

-

FASEB Journal express article 10.1096/fj.05-4985fje. Published online December 20, 2005

-

Muscle Nerve 1991. 14, 598–604

-

Am J Physiol 1996. Nov;271(5 Pt 1):E821-6

-

Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2002. Feb;282(2):E474-82

-

J Physiol 2011. 589, 963–973

-

J Physiol 2013. 591(18); pp 4655–4666

-

Am J Clin Nutr 2016 103: 276-282

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.