You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Optimum stride length for runners? Let your brain decide!

Although it might not be something you’ve given a lot of thought to, it turns out that optimising stride length is quite a hot topic among many runners, and quite a few running coaches too. The theory is that by consciously adjusting stride length, runners can become more efficient at running, needing less oxygen to sustain a given running pace – or to put it another way, will be able to sustain a faster pace without becoming excessively fatigued. But just how true is this? Can the brain’s mechanism of control be improved upon? Is there any evidence that we enhance our running efficiency by subtly increasing or decreasing stride length? While this sounds plausible, the science to date says no.

Although it might not be something you’ve given a lot of thought to, it turns out that optimising stride length is quite a hot topic among many runners, and quite a few running coaches too. The theory is that by consciously adjusting stride length, runners can become more efficient at running, needing less oxygen to sustain a given running pace – or to put it another way, will be able to sustain a faster pace without becoming excessively fatigued. But just how true is this? Can the brain’s mechanism of control be improved upon? Is there any evidence that we enhance our running efficiency by subtly increasing or decreasing stride length? While this sounds plausible, the science to date says no.The brain knows best

In a 2007 study, researchers studied the optimal stride frequency and running economy (efficiency) in 16 trained runners during an intense 1-hour run(1). Note that stride frequency is inversely related to stride length – for any given speed, a higher steps per second frequency equates to a shorter stride length. What they found was that as the run progressed and fatigue set in, the stride length tended to become shorter. However, when they asked the runners to artificially increase or decrease their stride length at any point during the run, the runners always became less efficient. In other words, their naturally preferred stride length (selected by the brain) at any point in the run was always the most efficient.What about experience?

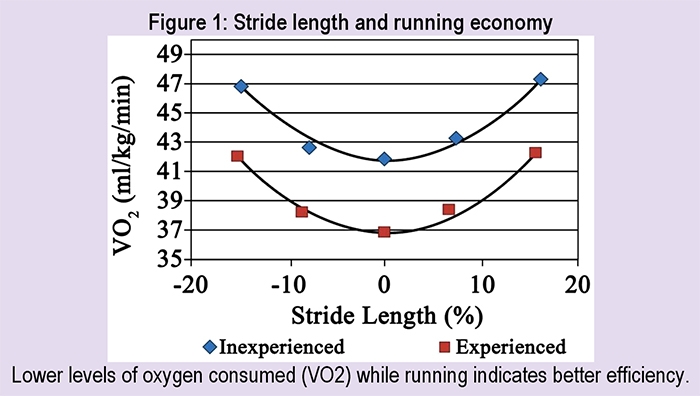

Some coaches have argued that while allowing the brain to determine optimum stride length is fine for experienced runners, inexperienced and novice runners could still need guidance, because their brains haven’t clocked up enough running miles to self determine optimum efficiency. But a much more recent study blows this theory out of the water. The study, published in the International Journal of Exercise Science, measured the energy use of 33 runners while using various stride lengths during a 20-minute run(2). Of those runners, 19 were experienced runners (meaning they averaged at least 20 miles a week) while 14 were inexperienced runners (people who have never run more than 5 miles in a week).During their runs, participants used five different stride lengths: their natural stride, and then strides of plus and minus 8 and 16 percent of their normal stride length. The results showed both the experienced and the inexperienced runners were most efficient when they were using their preferred stride as chosen by the brain (see figure 1). In a nutshell, you don't need to alter your stride length when running economy is the main concern. As the lead researcher, Professor Hunter, put it: "Just let it [stride length] happen; it doesn't need to be coached."

The bottom line - efficiency matters

The bottom line is that when performance matters, your brain knows how best to adjust your stride length to maximise your efficiency. So forget stuff like ‘stride-length’ or ‘cadence’ training programmes, and don’t listen to what others might tell you. Trust your body instead. When it comes to maximising running efficiency, there are much better - and scientifically proven - methods to achieve this. In particular, the appropriate use of some strength training and the right nutritional approach can yield real benefits. You can read more about these techniques and how to apply them in the links below.Andrew Hamilton, Sports Performance Bulletin editor

References

1) Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007 Aug;100(6):653-6

2) Int J Exerc Sci. 2017 May 1;10(3):446-453

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.