You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Prepare for action: why expectations matter!

SPB looks new research on how an athlete’s expectations of the benefits of a particular warm up can influence subsequent performance

The ‘placebo effect’ has long been documented in medicine. Essentially this effect occurs when the mere belief that a medicine or some other form of treatment will provide benefits, actually produces benefits, even if that treatment or medicine is nothing more than a sham - a completely inert substance that could not possibly benefit the patient in any physiological way. But the placebo effect doesn’t just occur in medicine. When maximizing physical performance is the goal, athletes are often seduced by the placebo effect, spending large amounts of money on products or strategies where there is no solid evidence that a particular treatment provides meaningful physiological performance benefits.

Sports nutrition and the placebo effect

The placebo effect in sports nutrition is very powerful and relevant for athletes. Studies clearly show that giving a completely inert pill boosts performance compared to giving no pill or treatment at all, even when athletes understand that the placebo pill could not have exerted any physiological effects whatsoever(1)! The implication of this finding is that even when a sports supplement possesses a real physiological boost to performance, some of that performance boost comes from the mere act of taking a pill. Indeed, it even turns out that the physical characteristics of a supplement and the amount of choice in the decision to take it (ie whether it’s your choice or on the recommendation of a coach/trainer) can determine the extent of the placebo effect you will receive(2,3).

In a recent SPB article, we also highlighted research showing that the ‘nocebo’ effect is powerful in sports nutrition too(4). Essentially, the nocebo effect is the reverse of the placebo effect, where an athlete performs more poorly because he/she believes that something they are taking will harm performance - when in reality there is no way a harmful effect could occur. For example, an athlete who regularly consumes a certain brand of oat cereal for breakfast might believe that a different brand of oat cereal results in less energy during morning training (and therefore perceive more fatigue), even if both cereals are actually produced by the same manufacturer in the same factory using identical ingredients with identical processing. The nocebo effect can also be observed in other aspects of athletes’ behaviours(5) – for example an athlete who believes that he/she performs better when tying left shoe laces before right, doesn’t follow this procedure, and then feels worse during training/competition as a result!

The placebo effect and communication

If an athlete’s beliefs and expectations about a supplement can affect subsequent performance, the obvious question is whether a placebo effect can occur merely by verbal communication and feedback that induces certain beliefs and expectations? Intuitively, you might expect this to be true and research to date suggests that this is indeed the case.

Studies have found that verbally-induced expectations and beliefs about an athlete’s own abilities and the effectiveness of ergogenic aids were shown to exert both positive (placebo) and negative (nocebo) effects on motor performance(6). This verbally-induced ‘treatment’ to produce a placebo effect can be either explicit or implicit(7).

When the communication is explicit, athletes are told outright that a certain strategy or treatment will produce benefits (or harms in the case of a nocebo effect). Implicit communication on the other hand merely hints at an effect and leaves the athletes to connect up the dots. Explicit verbal information to an athlete produces a stronger placebo effect than implicit information, and fairly recent research also shows that when verbal suggestions are combined with a ‘conditioning treatment’ (ie verbal information is given and then an athlete carries out a pre-exercise task based on that information), an even stronger placebo effect can be induced that verbal feedback alone(8).

Warming up: beliefs and expectations

If verbal information and advice can exert a placebo effect before a bout of exercise, perhaps the ideal opportunity to apply this effect is in a pre-exercise warm up? After all, a warm-up supervised by a coach or trainer provides the opportunity to impart explicit information conducive to a placebo effect, and then reinforce that information with a conditioning treatment – ie the actual warm up exercises themselves. To test this theory, a team of Italian scientists have carried out a study on the placebo effect of a warm up, the results of which have just been published(9).

New research

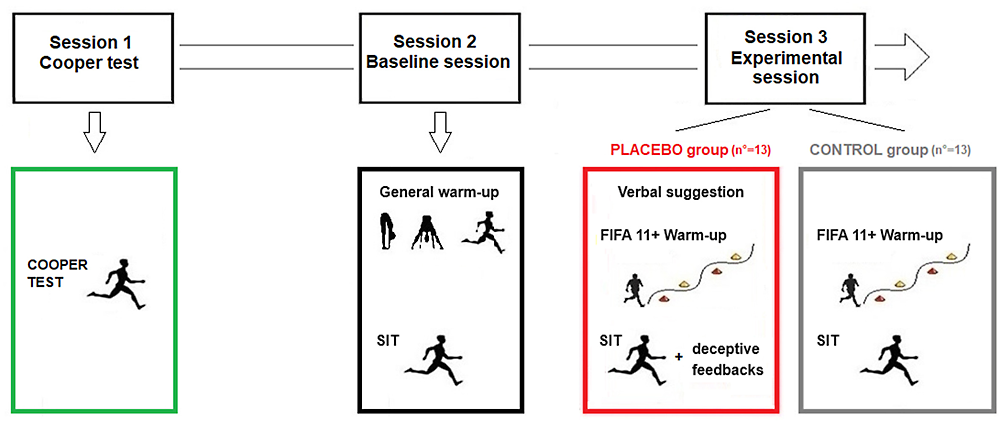

Published in the journal ‘Psychology or Sport and Exercise’, this research investigated the effects of a pre-running task warm up that was known NOT to enhance performance (ie a placebo) combined with verbal instructions designed to reinforce the placebo effect. Twenty-six recreationally trained university students, with an average weekly training volume of about 150 minutes per week, were enrolled for the study and divided into two groups – placebo (5 females, 8 males) and control (6 females, 7 males). In this investigation, all the participants performed three sessions (as outlined in figure 1). These sessions were as follows:

1. In Session #1, all the participants performed the Cooper Test to determine participants’ training level.

2. In Session #2 (a baseline session), all the participants first performed a general running-oriented warm-up. This warm-up consisted of 10 minutes of running at an intensity corresponding to 60% of VO2max plus 10 minutes of lower limb dynamic stretching exercises and 4 × 10m sprints. After this, there followed a repeated sprint interval test until exhaustion was reached. This test comprised of all-out 30-second running intervals, with rests of three minutes in between each sprint.

3. In session #3, the participants performed the same repeated sprint interval test as in session #2, but this time the warm-up was not a general running warm up but instead the FIFA 11+ warm-up (see here for a full description of warm up –up exercises). This warm-up, while known to help reduce injuries in soccer players, does NOT enhance running performance compared to a running-oriented warm up(10).

When it came to performing the repeated sprint interval test in session #3, this was where the students received either a placebo or a control condition. In the placebo group, the students received verbal suggestions to manipulate their expectations of the FIFA11+ warm-up effectiveness in improving performance. This verbal suggestion was a follows: “The FIFA 11+ warm-up will improve your performance compared to the general running warm-up carried out in Session 2”. In addition, during each sprint interval recovery bout, deceptive feedback was given to the students (ie they were lied to!). This feedback was along the lines of “Your performance in session #3 is improving compared to session #2”. In the control group meanwhile (which had also performed the FIFA 11+ warm-up, NO verbal suggestions were given about it enhancing performance and no deceptive feedback was given at any point during the sprint-interval test.

Figure 1: Schematic showing the overall study design

What they measured

The main outcomes measured were total running time and total distance covered. If the placebo effect was present through verbal information and feedback, both of these parameters would increase. Running time was considered as the outcome and was calculated as the subject’s running time recorded during each running phase minus the duration of all recovery bouts. Total running distance (TRD) was also assessed to measure running performance; this was simply the subject’s total distance covered during the sprint interval test until exhaustion was reached. In addition, the students’ perceptions were measured using the Borg 6-20 scale. In addition, heart rates and blood lactate concentrations were also monitored to measure the students’ physiological responses during the sprint interval task.

What they found

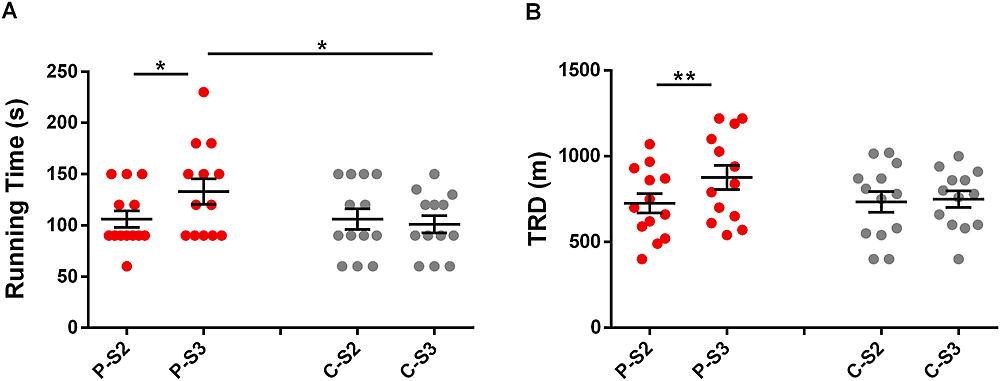

When the results were collected and analyzed, the result were pretty unequivocal; compared to test #2, both accumulated running time and total running distance in test #3 were significantly increased in the placebo group (who received positive verbal information and feedback). By contrast, whereas no performance were seen in the control group (who received no verbal information or feedback) – see figure 2. In the placebo group, the total running distance increased significantly from 730m in session #2 to 813m in session #3 – an increase of 83 metres covered. In the control group however session #2 distances averaged 734m whereas in session #3, they averaged 750m (an increase of just 16m, which was so small, it was statistically insignificant). Surprisingly perhaps, while the placebo group worked harder and performed significantly better in session #3, there were no increases in blood lactate or perceived effort in that session compared to session #2.

Figure 2: Running time and total running distance – placebo-vs. control

Related Files

A (left) – accumulated running time. B (right) – total running distance. Dots show individual results; horizontal bars show average. P-S2 and P-S3 = placebo group results in sessions #2 and #3 respectively. C-S2 and C-S3 = control group results in sessions #2 and #3 respectively. Significant performance improvements in both running time and total distance were seen in session #3 compared to #2 in the placebo group (who received verbal info and feedback). This effect was NOT seen in the control group.

Implications for athletes

In their summing up conclusions, the study authors wrote that their findings should encourage coaches to adopt this innovative method prior to training or competition to enhance athletes’ performance – ie to give a slight variation on a warm-up while telling athletes that this new variation will enhance performance (despite any evidence showing this!). Certainly, as a coach, there is much to be said for this approach. The power of the placebo effect is strong, especially when verbal information is given then backed up with some kind of exercise-based task, and trying out this approach does not require additional time, tools or resources, making it easily applicable anytime and anywhere.

More generally, these findings demonstrate once again that the placebo effect can be harnessed as a powerful tool to enhance performance. While it might sound rather woolly and vague, the power of positive suggestion really cannot be overestimated. This is entirely consistent with what we know about the role of the brain and belief systems in performance.

For example, studies show that when your mood state is elevated by the use of music, you can exercise at a higher intensity but your perception of effort doesn’t change(11). Likewise, expectations and beliefs can also affect your performance. For example, runners who are told that they will be completing 10km run experience a sudden jump in perceived effort if, halfway through that run, they are told that the run distance is not 10km but is in fact 20km(12). In addition, research has demonstrated that it’s possible to boost performance by ‘fooling’ the brain. For example, cyclists who believed that they were cycling at their best ever time trial speeds were deceived by researchers who set it 2% faster, resulting in significant improvements the cyclists’ personal bests – something they thought was not possible(13)!

In summary then, if you have strong ideas and beliefs that certain pre-competition supplements, routines and other treatments or regime will help your performance, there’s every chance – due to the placebo effect – that they will. Therefore, there’s no particular reason to abandon them! In addition, it’s likely that practising mental strategies that induce positive thoughts and expectations in the brain are also likely to help. There are plenty of advice guides in the literature aimed at positive thinking in sport performance but this SPB article by Lee Crust provides a good starting point.

References

1. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021 Aug 1;53(8):1766-177

2. PLoS One. 2018 Jun 11;13(6):e0198388

3. Ann Behav Med. 2022 Oct 3;56(10):977-988

4. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2023 Nov-Dec; 17(6): 39–42

5. Eur J Sport Sci. 2020 Apr;20(3):279-292

6. European Journal of Sport Science 2020. 20 (3) pp. 293-301

7. Psychological Bulletin 2004. 130, pp. 324-340

8. International Review of Neurobiology 2018. 139, pp. 297-319

9. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2024 Mar 26:102633. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2024.102633. Online ahead of print

10. Clin Rehabil. 2017 May;31(5):651-659

11. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015 May;47(5):1052-60

12. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011 Feb;36(1):23-35

13. Int J Sports Med. 2016 May;37(5):341-6

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.