You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Tuning your training: should you factor in body type?

SPB explores the science of body types; what are these types and should your body type affect the way you train?

It’s a fact of life that we all have unique genetics, and that those genetics profoundly affect our body’s shape, metabolism and responses to training. Indeed, you probably know of people who naturally stay lean and slender no matter what they eat, or those who can seemingly gain copious amounts of strength and muscle by merely looking at a barbell! But given we all tend towards a certain type of metabolism and certain type of body shape, can this impact and influence the way that you train?

Unraveling body types

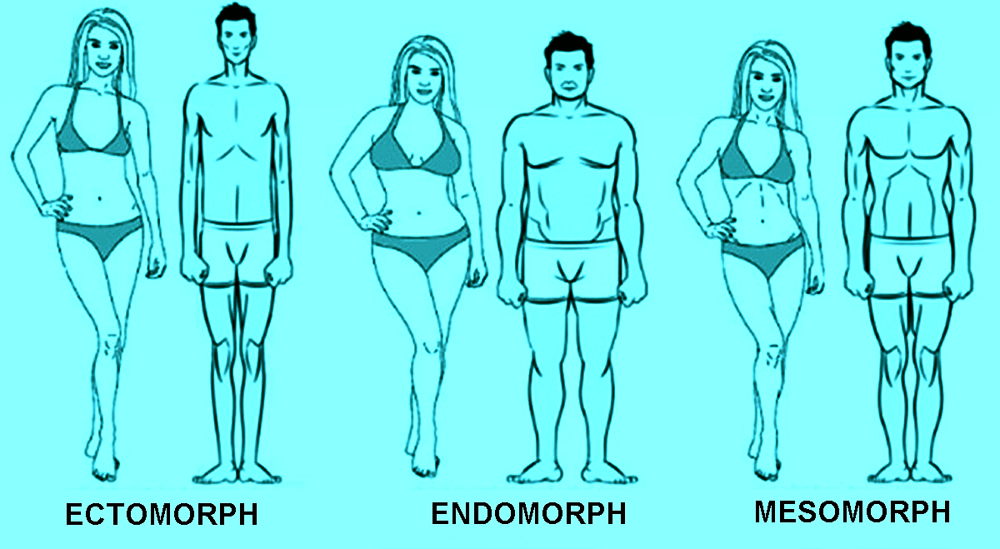

Nearly 70 years ago, a physiologist by the name of Sheldon was trying to classify different body types by examining characteristics such as body proportion, bone structure and body fat levels(1). He came up with three essential body types, known as ectomorphs, mesomorphs and endomorphs (see figure 1). In brief, ectomorphic body types were characterized as slim, tall, with less muscle mass and less tendency to gain body mass. Endomorphic body types were characterized as shorter in height with higher levels of muscle and body fat and with a tendency to gain weight easily. Mesomorphic body types meanwhile were characterized as naturally muscular and athletic, not especially tall or short, slim waisted, and with no particular tendency to gain or lose weight.

Figure 1: Sheldon’s body type classification

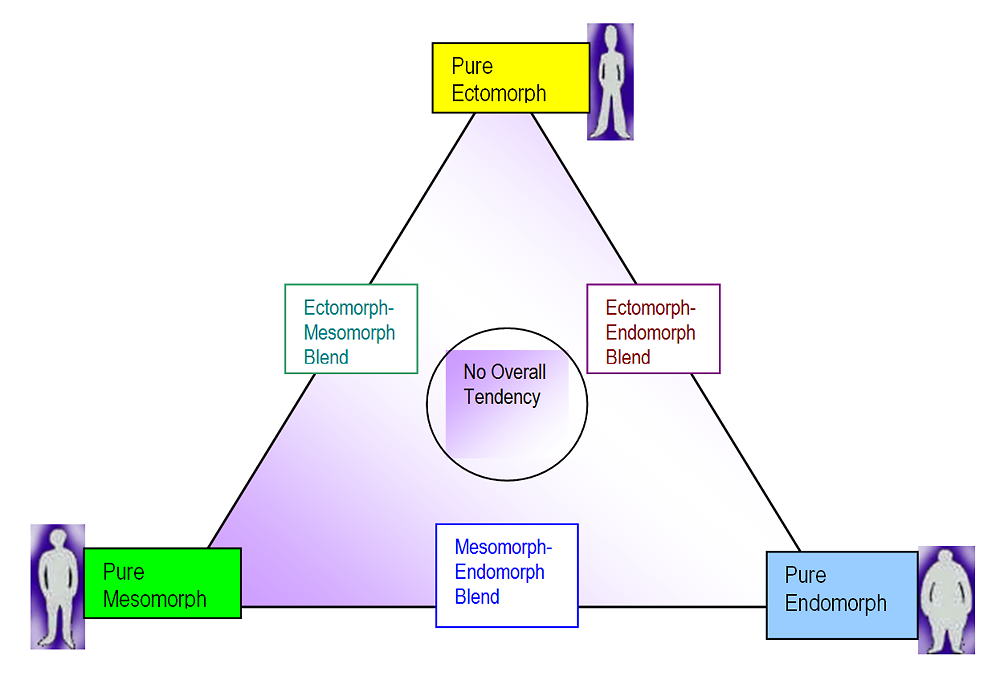

Although Sheldon’s classification system was simple and easily understood, it had major flaws – not least because very few people fit neatly into one category, but instead have traits or tendencies of one of more of these body types. Over the years therefore, there were several attempts to refine this system of classification by allowing for a number of varying levels of fatness and thinness within each body type and the distribution of body fat across the body.

A good example is the Heath–Carter classification system(2). This uses an individual’s weight, height, upper arm circumference, maximal calf circumference, femur (thigh bone) breadth, humerus (upper arm bone) breadth, and skinfold fat measurements from four sites across the body and combines these in a series of equations to assess a subject’s traits against each of the three somatotypes, each assessed on a seven-point scale, with 0 indicating no correlation and 7 indicating a very strong correlation. In other words, it arrives at a tendency to a body type rather than an absolute classification, and places individuals on a spectrum of body types rather than pigeonholing them into one extreme (see figure 2). The Heath-Carter classification system is widely use in a number of sports, including rowing(3), tennis(4), gymnastics(5), soccer(6) and triathlon(7).

Figure 2: The spectrum of body types

Related Files

Before moving onto the training implications for different body types, it’s worth re-emphasizing that the categories are very broad, so it’s easy to oversimplify a body type and end up pigeonholing someone without adequately considering other important characteristics. As the reader, while you may have a tendency towards one of these types, you’ll almost certainly have supporting characteristics of one of the other types too. The second concerns the debate over Nature vs. nurture. Your body type is strongly inherited via genes(8); while some people feel frustrated about the genetic body type dealt to them by Nature, it’s important to realize that many these genetic traits result in tendencies, not pre-determined outcomes. The way you are is and always will depend on the interaction between those genetic tendencies and your environment. In plain English, whatever your ‘body type’, the way it expresses itself will depend on what you do with your body in the real world.

Body type characteristics

As we explained above, you can think of pure ectomorphic, mesomorphic and endomorphic characteristics as extreme points on the three apexes of a triangle (figure 2). Most of us lie somewhere inside this imaginary triangle with a blend of these characteristics. We also need to dispel the notion that it’s ‘better’ to have one type of body over another. While certain body types may have a physiological advantage in certain types of sports, if you look at table 1 below, it’s clear that each body type carries both training advantages and disadvantages.

Table 1: Metabolic characteristics and training advantages/disadvantages

|

Body type |

Physical characteristics |

Metabolic characteristics |

Training advantages |

Training disadvantages |

|

Mesomorphic |

Fairly tall & athletic looking; broad shoulders; narrow waists; broad hips; upright posture; more muscular and ‘rectangular appearance’ |

Mesomorphs have a fairly fast metabolism and they can both gain and lose weight quite easily depending on their environment. Mesomorphs also respond well to training and can gain muscle quite easily;. |

Mesomorphs respond very well to a variety of training types. They see results rapidly and can achieve both low body fat and high levels of musculature. |

Mesomorphs have a tendency to become stale, over-trained or injured and can easily gain weight once training is discontinued. |

|

Endomorphic |

Strong bone structure; rounded appearance; ‘softer’ body with less well defined musculature; shorter leg bones |

Endomorphs have a slower metabolism but also a ‘strong constitution’. They gain muscle and weight easily and find it harder to lose weight. |

Endomorphs are naturally strong and powerful; they respond very well to resistance training and are less likely to become injured or overtrained. |

Endomorphs have more difficulty losing body fat. Dietary vigilance and plenty of aerobic type exercise are required counteract this tendency. |

|

Ectomorphic |

Tall and slender; delicate build; small bone structure; young appearance; thin chest; small hips and waist |

Ectomorphs have a fast metabolism, are slow to gain muscle, lose weight easily and have difficulty in gaining weight. |

Ectomorphs find it easy to lose & keep off excess body weight very easily. They’re often naturally good at endurance types of exercise, especially where low body weight is an advantage such as running. |

They struggle to build strength and their smaller bone and muscle structure makes ectomorphs much more injury-prone. Vigorous exercise may cause excessive weight loss, below that considered healthy. |

Sport and body type

Take a look at runners in an elite distance running race and it’s likely that many of the runners will have strong ectomorph characteristics(9). But how much of that characteristic is due to the training and how much is inherent? Some researchers have speculated that training for sports brings about the kind of physical changes in body composition and shape needed for success(10). However, others have suggested it’s the other way round – ie individuals with existing morphological traits become most successful if they enter specific sports(11). In reality, it’s very likely to be a combination of both – ie an interaction between somebody’s genes/inherited body type and behavioural/environmental factors(12).

Take for example someone with strong endomorphic characteristics who engages in both rugby and distance running during school years. With a robust constitution and good levels of natural strength, this person might well excel at rugby, and experience plenty of positive feedback as a result. However, their heavier and more powerful constitution would likely work against them in distance running, leading to a less positive experience. Even though their body shape would become more suited to distance running with more running training, they may well prefer to take up rugby as a sport once the choice is optional; indeed data shows that greater muscle mass/strength, body fat levels adiposity and bone size are desirable for tackling and attacking in rugby, which puts endomorphic player with mesomorphic tendencies at a distinct advantage(13,14).

Insight from triathletes

To gain a little more insight, an early study by US scientists on female triathletes makes for fascinating reading. In the early days of triathlon, there was much debate on what made a ‘good’ triathlete – specifically, whether triathlon success was more likely if they shared the body type of elite runners, swimmers or cyclists(15). When compared to Olympic swimmers and runners, the triathletes tended to be somewhat shorter with a balanced body type that tended to be more mesomorphic than the other body types. Compared to Olympic runners, the triathletes were generally heavier, less lean, more mesomorphic and less ectomorphic than elite runners. Because of lack of information on cyclists, adequate comparisons were not possible. However, the really important take-home point was that while body type did help to some extent in predicting performance, it was the training parameters were more important than anthropometric measures in determining how successful the triathletes were.

Body type and training recommendations

If we all have a tendency to a body type and that body type comes with certain physiological characteristics, should a training program be adapted to reflect body type? There’s no simple answer to this question as it all depends on what you’re trying to achieve want and the body type/tendency you have. So if you’re an ectomorph training for a marathon, your body type is already ideally suited to the task. Rather than try and train to develop more mesomorphic or endomorphic characteristics, you’ll be quite happy to exploit the body type you already have. The same could also be said for an endomorph in training for power lifting or rugby, or a mesomorph in 400m running.

However, let’s suppose you have a body type that definitely leans towards one of the three categories, but that you want to train for overall fitness and to develop a well-balanced blend of stamina, strength and power. Are there any ‘body type’ training guidelines you can follow? The answer is yes, but these guidelines are more about shifting the emphasis of your training rather than forming the program itself. You still have to think about things such as your overall goals and objectives, your current fitness level and training history, whether or not you have any injuries that might affect the way you train and of course your own personal preferences when training. But once you’ve come up with a training program that ticks the right boxes, you can then apply some guidelines to help produce more balanced results for your particular body type.

It’s important to underline that these guidelines are not based on the result of specific studies on somatypes and training programs – simply because these haven’t been carried out. They are however, based on widely accepted acknowledged sports training principles, which means they have a fair degree of validity. Bear in mind though that these are very general recommendations for those seeking a good blend of endurance and strength. They are not necessarily appropriate for athletes training for a specific sport - although by understanding what’s needed to adapt a program to develop all-round fitness, you can gain an insight into how to tweak your sport-specific program!

Ectomorph training

Ectomorphs lose weight easily because of their high metabolic rates, but find it hard to gain strength, power and muscle. Ectomorphs seeking ‘balance’ should spend less time engaged in high-volume, steady-state endurance type exercise and more time doing high quality intervals and reasonably intense resistance training (to maintain strength levels). For strength building, the overall training volume however should be kept down (otherwise it will tend to raise an already active metabolism and prevent gains from being made) while the emphasis needs to be on the core compound exercises such as chest press, leg press, lat pulldowns/chins, dips and squats. High-repetition isolation work is not recommended.

|

ECTOMORPHIC |

Volume |

Intensity |

Type |

Notes |

|

Endurance training |

Where strength preservation is important, keep it fairly low Three sessions of up to one hour per week is adequate. Good recovery and post-exercise feeding especially important. |

Quality matters Emphasize higher-intensity work and include regular intervals. |

Smooth non-weight bearing movements like cycling rowing and swimming are better for preserving muscle mass. Pounding movements against gravity like running, are less so as they tend to induce muscle mass loss. |

Ectomorphs in training for endurance sports will need to engage in higher volumes of endurance training. |

|

Strength training |

Low – keep the volume low. Train each body part no more than once every 4 or 5 days and allow for full recovery between workouts. Stick to 2-3 very high quality sets per body part. |

High – use heavier weights at between 6-10 reps per set aiming to reach very near the point of failure at the end of each set (excluding warm-up set) |

Stick to basic movements such as squats, bench press, chins, etc. Ectomorphs sometimes need a little upper body emphasis. |

Quality, not volume is the real key to success for ectomorphs wishing to gain strength. |

Endomorph training

If you’re more endomorphic in body type, you’ll tend to have plenty of natural strength and a high tolerance to hard training. However, the flipside is that with their inherently slower metabolisms, endomorphic types typically need to perform higher training volumes and place a greater emphasis on endurance types of exercise, in order to maintain an optimum level of body fat for an overall all-round balanced performance. Resistance training shouldn’t be ignored, because it raises the body’s basal metabolic rate – exactly what endomorphs need. However, unless you’re training for a sport where high levels of strength are needed, this strength work should be of the higher volume, lower intensity type, and considered secondary to endurance training.

|

ENDOMORPHIC |

Volume |

Intensity |

Type |

Notes |

|

Endurance training |

Higher Sessions of at least 45 minutes should be performed most days of the week. Of course, this will depend on fitness level and will not apply to athletes training for a strength sport. |

Low to moderate. Longer, less intense aerobic workouts at around 65 – 75% of maximum heart rate will promote more fat-burning than shorter more intense sessions and are better suited to the high volumes required. |

Weight bearing exercises against gravity (e.g. running, hill walking and cycling) will be more effective at promoting fat loss compared to weight supported exercises like swimming. |

High volumes of pounding exercise are unlike to be suitable for those who are substantially overweight or with a history of lower limb/back injuries. |

|

Strength training |

Moderate to high. Aim for one or two full body workouts a week. Your high tolerance to resistance work means you can perform plenty of sets per body part. |

Low Using lighter weights but higher repetitions of around 10-15 per set will still maintain strength but will also burn more calories. For maximum strength however, 6-10 reps is recommended. |

Include plenty of lower body exercises – this is where the largest muscles are. Use a wide variety of movements. |

Keeping your heart rate raised during training will produce extra endurance and calorie-burning benefits - keep your rest between sets to a minimum and move quickly through your circuit. |

Mesomorph training

The mesomorphic body type lies somewhere in between the other two, which is reflected in the training recommendations. However, to make good progress and avoid becoming stale, training variety is crucial for mesomorphs. For good aerobic gains and overall balanced fitness gains, endurance workouts should be at a variety of different intensities, while a mesomorph’s resistance program should include both compound movements for building and maintaining strength and higher rep isolation work for improving muscle definition. While galling, it’s a fact that very mesomorphic types can get away with doing less and achieving more! The downside however is that because they see results so quickly (even repeating the same routine over and over again will almost certainly produce results) mesomorphs are also more prone to overtraining. To avoid falling into this trap, mesomorphs need to change their training routines frequently.

|

MESOMORPHIC |

Volume |

Intensity |

Type |

Notes |

|

Endurance training |

Moderate 3 – 5 sessions of mixed duration endurance sessions per week work well - e.g. 2-3 shorter, higher intensity sessions 1-2 longer sessions. |

Mixed E.g. shorter sessions at around 85% of maximum heart rate; longer sessions performed at around 70% maximum heart rate. |

Mesomorphs respond well to all types of aerobic training. |

Whichever endurance training mode mesomorphs engage in, the key to progress is varying workout intensities and duration |

|

Strength training |

Moderate. A maximum of 2 sessions a week is ample for most mesomorphs. These should include 4-6 exercises per body part. |

Mixed. Mesomorphs should mix lower repetition, higher intensity workouts (e.g. 6-8 reps per set) with slightly higher rep, lower intensity workouts (10-12 reps per set). To avoid overtraining, heavier training periods should be interspersed with lighter periods to allow full recovery. |

The tried and tested formula of performing a basic compound exercise, followed by an isolation exercise works well for mesomorphs. The exercises and the order in which they’re performed should be changed frequently. |

Beware of overtraining and getting stuck in a rut. |

References

1. Sheldon, W.H. (1954). Atlas of Men: A guide for somatotyping the adult male at all ages. New York: Harper

2. Norton, Kevin; Olds, Tim (1996). Anthropometrica: A Textbook of Body Measurement for Sports and Health Courses. Australian Sports Commission; UNSW Press

3. Journal of Sports Sciences 2007. 25 (1): 43–53

4. Br J Sports Med 2007. 41 (11): 793–799

5. Journal of Human Kinetics 2014. 40 (1): 181–187

6. Brazilian Journal of Kineanthropometry & Human Performance 2013. 15 (2): 184

7. Journal of Sports Sciences 1991. 9 (2): 125–135

8. Int J Obes. 2007; 31: 1295–301

9. J Sports Sci. 1991 Summer;9(2):125-35

10. Somatotype in relation to physical performance, sports and body posture In: Reilly T, Watkins J, Borms J, Kinanthropometry III. London: E and FN Spon; 1986

11. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 1966; 6(2): 89–91

12. Developmental Science. 2007; 10(1): 1–11

13. J Sports Sci. 2001 Apr;19(4):253-62

14. J Sci Med Sport. 2014 Sep;17(5):546-51

15. J Sports Sci. 1991 Summer;9(2):125-35

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.