You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Breathing technique: getting that gut feeling

One of my most vivid sports memories is the moment I learned how to breathe. I was a 24-year-old graduate student doing a clerkship in Seattle, Washington, dreaming of climbing the 4,400-metre volcano that tantalised me from my office window. I’d never been a runner, but running, I’d been told, was the best way to get in shape to breathe at those elevations, so I was putting in 5 kilometres several times a week, in the hope of being fit enough to reach the summit.

As the big day drew near, I got ambitious, and decided to go for a second lap of a favourite 4-kilometer route. Initially, that looked like a bad decision, as fatigue mounted and I struggled to keep going. Then suddenly, there was a surge of cool air to parts of my lungs I didn’t even know existed. Tiredness fell away, and I felt a rush of exhilaration I have never forgotten. At the time, I had no idea what had happened. All I knew was that I had discovered lung capacity I never knew existed.

Breathing facts

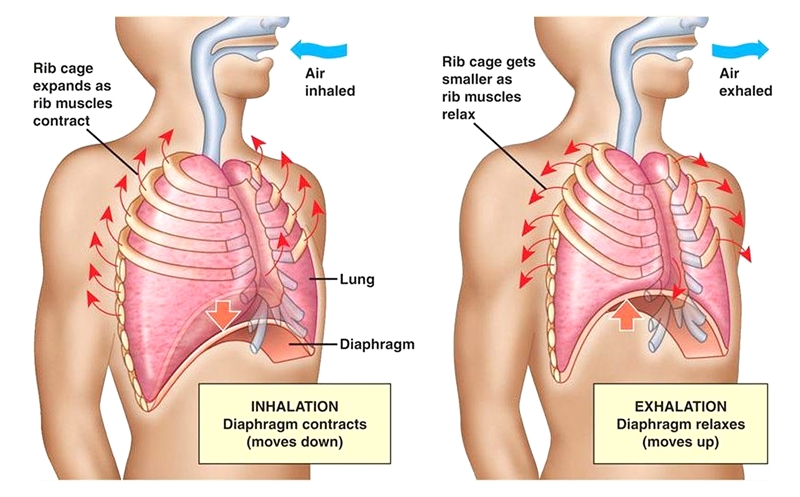

Breathing is something we normally do without conscious thought, somewhere between 17,000 and 26,000 times a day for the average adult. But when we are working close to our maximum work output (VO2max), scientists have found that the muscles involved in breathing can account for as much as 10 percent of our total oxygen consumption - simply in the effort to keep oxygen (in the air) coming in as fast as we need itJ Appl Physiol 1992; 72: 1818–1825. Doi:10.1152/jappl.1992.72.5.1818. In other words, the muscles we use to breathe (see figure 1) are important. Especially when something goes wrong, as in the notorious side stitch, which can be so painful that some people who’ve never experienced it before may think they’re having a heart attack!

During inhalation, the diaphragm and external intercostals (rib muscles) contract to make the thoracic cavity larger. This is an active process, which requires muscle action and uses oxygen.

During exhalation, the diaphragm and external intercostals (rib muscles) relax and the thoracic cavity becomes smaller. This is a passive process when at rest, but during exercise (when breathing is much more vigorous and rapid), it becomes an active process, also consuming oxygen.

When a stitch occurs, most athletes simply slow down and pray for relief. But I’ve known elite runners to attempt to power through it so strongly they hurt for days afterward. In 1982, in his third New York City Marathon win, for example, Alberto Salazar once told me he suffered from such a severe stitch that he had to adjust his race plan. He dropped off pace, letting his top rival think he’d been broken, until finally the stitch relented enough to let him fight back for the win (figure 2). Afterwards, Salazar said it hurt every time he ran for a full three weeks!

Chest breathing

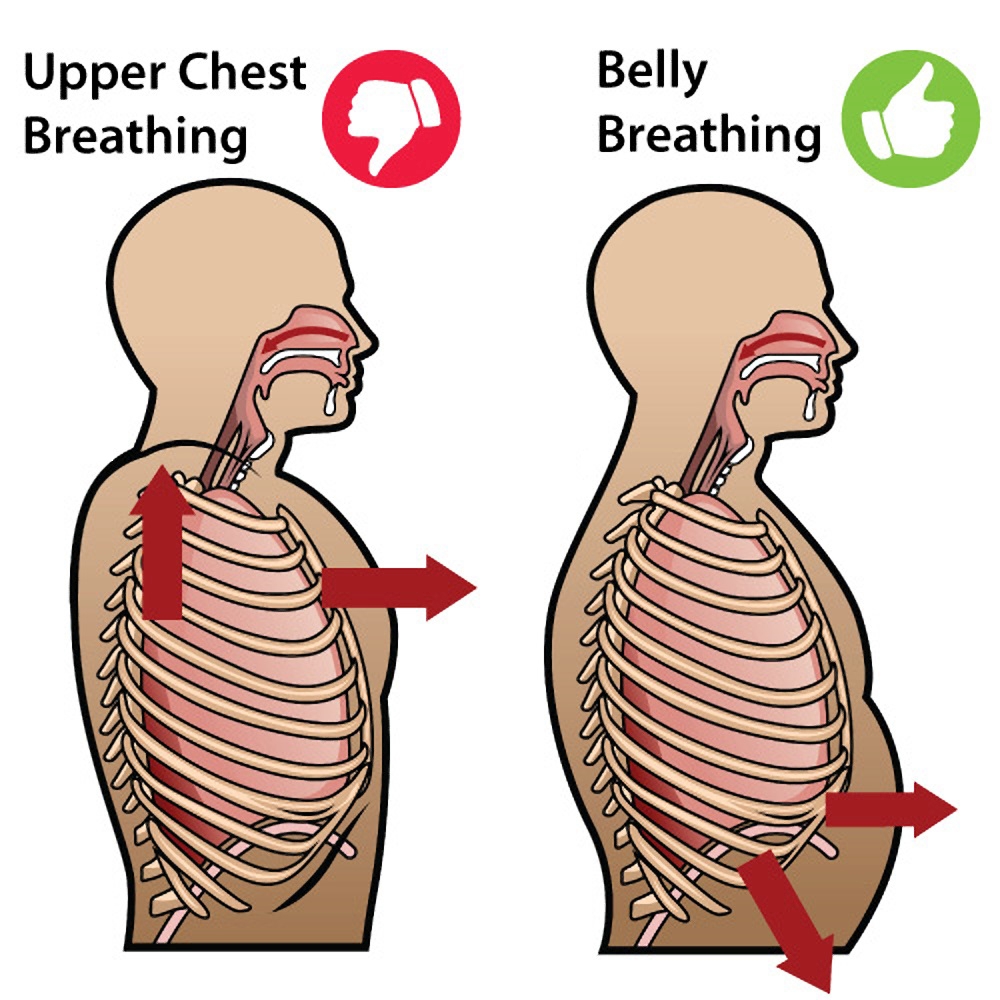

Doctors aren’t in full agreement over what exactly a side stitch is, but it almost certainly comes from abusing your diaphragm badly enough to produce something akin to a cramp or, in extreme cases like Salazar’s, a muscle strain. If you want to experience one, eat a big meal and immediately go for a hard workout; all that food in your stomach is likely to make your diaphragm very unhappy. However, there are other things that can contribute, and one of these is something called 'chest breathing'Current Sports Medicine Reports (2006), 5(6), pp 289-292, November 2006. Doi:10.1007/s11932-006-0055-7.Chest breathing occurs when you breathe primarily with your upper chest muscles, rather than your diaphragm. One way this can become a habit is when we become self-conscious about how others perceive our bodies, and we start trying to suck in our gut and throw out our chest while breathing in. I myself was actually taught to do this in posture classes when I was nine or ten years old. Most people probably pick it up from peer pressure, later on.

The problem is that however sexy this might make you look, it constricts your breathing. In normal breathing, your diaphragm moves downward, acting like a bellows that expands your lungs (figure 1). But this downward motion means that everything below it has to go somewhere, and that somewhere is outward. If vanity causes you tighten your tummy in a refusal to let this happen, the result is an impasse. The diaphragm wants to do one thing; the abdominal muscles of the tummy want to do the opposite, and eventually the diaphragm, the weaker muscle, gives up and cramps.

This is particularly likely to occur at the points where either the stomach or the liver repeatedly bang into the diaphragm on each stride, one on the left, and one on the right. As a coach, I cannot count the number of times I’ve had athletes complain of stitches, only to discover that they were chest breathers.

Belly solution

So how do you deal with this? The first step is diagnosing the problem. Put your hand on your stomach, approximately on your belly button. Take a deep breath, and watch the movement of your hand. If it goes outward, away from your spine, congratulations, you’re a belly breather—the opposite of a chest breather. You are using your diaphragm the way nature intended. But if you hand goes upward, (toward your head), you are a chest breather. Figure 3 shows the typical difference in movement patterns between these two breathing modes.

Even if you don’t get stitches, chest breathing restricts your lung capacity. Your right lung has three lobes, and chest breathing only gives you access to the upper two, according to Robyn Pester, a physiotherapist from Eugene, Oregon, USA, who has consulted with Nike track and field athletes as well professional golfers and basketball players. Your left lung (smaller, to make room for your heart), only has two lobes, but chest breathing only gives you access to one, she adds. These lobes aren’t the same size, but the idea is clear. This was the inrush of air I felt on that long-ago run, when I unknowingly forced myself to fill an extra two of my lungs’ five lobes.

Taking control

Changing from chest breathing to belly breathing isn’t easy. I myself was simply a beginner who got lucky. I accidentally put myself in an oxygen-deprived situation, and my body figured it out on its own. Experienced athletes may find the transition more difficult simply because they’ve already achieved significant success as chest breathers.The basic process is to find a way to force yourself to belly breathe, then become accustomed to what it feels like, so you can replicate it. Since most chest breathers can’t shift to chest breathing while standing up, a good idea is to lie down on your back and put a book or any other object on your stomach. Watch how it moves when you breathe.

Up and down is what you want. Back and forth, horizontally, isn’t. Try to make it go up when you breathe in (breathing in through your nose may help). Then, when you have achieved that, stand up and try doing the same thing. I’ve seen people get this on the first attempt…or struggle with it for months. A lot depends on how strongly your subconscious has assimilated the previous breathing motor patterns.

If lying on your back still doesn’t work, try standing up and performing a toe-touch. Cheat and bend your knees, if you can’t get your hands close to the ground. The goal here isn’t to stretch your hamstrings; it’s to force you into a doubled-over position in which it’s virtually impossible to chest breathe. Cyclists can do the same thing in the down position on the handlebars. Take a few deep breaths, observing what happens. Then lie on your back, trying to replicate it, after which you can try to reproduce that, standing up.

If you are still chest breathing, congratulations; you are in a small, unusual group. In all my years of coaching, I’ve only seen a handful of people who can’t be contorted into positions where they are forced to belly breathe. All have been either extremely petite or so inflexible they can’t get their hands within 30cms of their toes. If that’s you, all you can do is go back to lying on your back and trying to figure out how to make that book on your stomach to go upward, rather than toward your chin. Try to think of an expanding belly as your friend, rather than an enemy that must be constrained at all costs.

Crossover rhythm

Chest breathing isn’t the only cause of stitches. Research has found that most runners synchronise their breathing with their foot-strikesScience 1983. 219. 251-6. Doi:10.1126/science.6849136. Most employ a 2:1 ratio, in which they take a breath every two complete strides (ie every four foot plants). This synchronisation helps make breathing more efficient and helps stabilise the coreBreathe. 2016;12(2):165-168. doi:10.1183/20734735.008116. However, it also means that every breath comes with the same foot plant, whether it’s right-side or left-side. This means that each breath starts when the jarring of the foot plant is on the same leg. If you’re prone to side stitches and nothing else has gotten rid of them, you might try to adjust this. One trick is to shift the ‘lead’ leg in the 2:1 cycle. If you always start an inhalation when the right leg lands, try to shift to the left leg. That might be all it takes to make a stitch go away.Alternatively, you can try changing the rhythm. The same study that found that most people run and breathe in a 2:1 cadence also found that this cadence isn’t physiologically required. We can also run in rhythms of 4:1, 3:1, 1:1, 5:2, and 3:2. The last two of these mean that with each stride, we can switch the side on which the in-breath and impact occur, alternating between left and right. If nothing else, that allows us to beat up opposite sides of the diaphragm with each stride, delaying the time at which it rebels!

Diaphragm strengthening

Delaying stitches isn’t the only thing you can do by working on your breathing. A 2001 study of nationally competitive British female rowers found that a mere 30 breathing exercises performed twice a day, using a device designed to increase inhalation resistance to about 50 percent maximum effort, improved 5000meter time trial times by 3.1%, compared to only 0.9% percent for the control groupMedicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 33(5): 803-809 (2001). These devices (such as PowerBreathe – see figure 4) can be purchased online for prices ranging from £20 to £150 ($30 to $200) - fairly cheap investment for a competitor seeking a personal best.

A number of companies make devices designed to improve your diaphragm strength. Whichever one you try, follow the manufacturer’s instructions to set it to about 50 percent resistance, based on your current breathing strength. As with any new exercise program, remember that the goal isn’t to kill yourself the first day out of the gate! Start gently, building up to two sets of x 30 breaths, twice a day, for 5-6 days a week.

More recent work, from Canada suggests that the way these IMT devices work may not be so much from strengthening the lungs as by attenuating a process in the body called the 'metaboreflex'J Physiol 2007; 584: 1019–1028; doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2007.140855. This is where the body restricts blood flow to the limbs when the breathing muscles fatigue. The physiology is complex, but the idea fairly simple. When it comes to survival, continuing to be able to breathe is crucial - winning a race is not. So when the body senses a conflict between the two, it shuts down blood flow to the legs, sparing blood for the diaphragm and, in the process, allowing the diaphragm a chance to recover. If your diaphragm is strong, well-trained, and not on the verge of collapse, however, the body doesn’t need to do this, so a strong diaphragm means better blood supply to your legs, and better performance in any endurance sport in which the legs are involved.

Case study: Bob Williams

It was more than fifty years ago, but Bob Williams still recalls the day when legendary coach and Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman offered to teach him an important secret. “He put his hands on his belly and said, ‘This is your diaphragm and it’s going to help you be a very good runner,’” says Williams, who at the time was a 19-year-old on Bowerman’s University of Oregon team.

Bowerman then demonstrated belly breathing, adding that it would not only allow Williams to breathe more deeply, but would also help him manage stress when the going got tough. “He told me to practice lying down, putting a book on your tummy. Then practice sitting, walking, and while you’re in front of a mirror.”

Williams practiced and went on to win the 3000-meter steeplechase title in what would become today’s Pac-12 Conference. Now, as a coach who’s worked with everyone from high school students to Nike professionals, he still remembers that early lesson, and teaches it to the his own trainees. “I make it an emphasis,” he says. He also notes that practicing proper breathing is also a good way to help stave off pre-race nerves. “When you’re nervous you breathe shallowly,” he says. In fact, he says, “in a high level of anxiety, you’re breathing so shallowly that the potential of passing out is there.”

Pressure breathing

One of the many tricks legendary coach and Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman tried with his University of Oregon distance runners was something that Bob Williams says Bowerman picked up from Swedish exercise physiologists he’d met in the 1960s. The trick, Williams said, was to exhale with your cheeks puffed out. “There’s something about what he was having us do that made us feel better and race better,” Williams says.Bowerman had apparently stumbled on a trick known to mountaineers as ‘pressure breathing’, in which climbers exhale against resistance in order to (briefly) increase the air pressure in their lungs, thereby allowing their bodies to absorb more oxygen. It requires strong breathing muscles, but is a major reason why climbers have reached the summit of Mt. Everest without supplemental oxygen. For the rest of us, competing at sea level, it might well be a way to get a shot of extra oxygen into our bodies when we most need it most.

Summary

All told, the bottom line is simple. Breathing is the oft-forgotten component of competitive performance, and your diaphragm is one of your most important muscles, whether your sport is running, cycling, triathlon, swimming, cross-country skiing, or anything else in which endurance is a factor. And if you can get even a small improvement from working on your breathing for only a few minutes a day, trying it out seems like the classic no-brainer.Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Further reading

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.