You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

CrossFit athletes: an easier route to success

SPB looks at new research on how CrossFit and circuit-training athletes can achieve their performance goals with less training overload and fatigue

The sport of CrossFit has developed into a widely practiced sport over the past 20 years or so. Much of its appeal is that CrossFit athletes need to build and optimize a wide array of physical performance measures, such as strength, endurance, stamina, flexibility, power, speed, coordination, agility, balance, and motor skills(1). For this reason, it can be considered a truly comprehensive sport for developing total and all round fitness.

Training for CrossFit

Because of the nature of the event where athletes are subject to a large variety of physical demands in a short time (around 10 minutes or so), the basis of CrossFit training is built around ‘high-intensity functional interval training (HIFT)’. With a focus on varying functional movements, HIFT training incorporates key elements of gymnastics (eg handstand and ring exercises), weightlifting exercises such as barbell squats and presses, and traditional cardiovascular activities such as running or rowing – all performed in one training bout(2).

These HIFT exercises are typically performed quickly, repeatedly, and with comparatively high training intensity, while the inter-set recovery time is reduced(3). Although this form of training is demanding, it remains popular with CrossFit athletes since studies have shown that it can simultaneously develop both strength(4) and an increased maximal rate of oxygen consumption (VO2max)(5).

The downsides of HIFT

While undoubtedly effective, HIFT has a distinct downside in that the high intensity and training load can lead to considerable fatigue and delayed recovery. If recovery is not sufficient, this in turn can result in reduced performance, disturbed sleep, increased perceived fatigue, and a higher incidence of respiratory tract infections (coughs, colds, sore throats etc)(6,7). Importantly also, it’s during the recovery period where desirable training adaptations take place; therefore if recovery is not quite sufficient, the fitness gains resulting may fall short of what is potentially achievable(8).

Is CrossFit more endurance than strength?

While it seems intuitively right that athletes should conduct mainly HIFT to prepare for CrossFit competition, some recent research has questioned this approach. Based on the winning times of individual events (ie duration from start to finish) at the CrossFit Games during the(2017–2021 period, the actual loading time is 9.0 minutes for men and 8.8 minutes for women; likewise, an analysis of the CrossFit open workouts between 2011 and 2022 reveal similar average load times(9).

Looking at the exercise intensity required to maintain a high level of performance throughout these events, it becomes clear that while engaging both aerobic and anaerobic energy systems, CrossFit competition intensity lies within the intensity spectrum of many endurance-based activities. Given that’s the case, some researchers have questioned whether athletes undertaking training for CrossFit or other similar mixed endurance-strength activities should adopt the kind of training intensity distribution used by endurance athletes such as triathletes, cyclists, rowers etc.

In these endurance sports, athletes typically adopt a polarized approach to training (characterized by approximately 80%–95% of work done in zone 1 (below the first lactate threshold) and approximately 5%–20% in zone 3 (above the second lactate threshold) while avoiding the moderate threshold-based intensity – zone 2 (between the first and second lactate thresholds)(10). Another popular approach is the pyramidal structure, where slightly more moderate-intensity training is included than high-intensity training, resulting in approximately 60%–90% zone 1, 5%–30% zone 2, and 2%–10% zone 3 training(11).

Polarized training for CrossFit

Given the above, could a more endurance-based approach such as polarized training intensity distribution be equally as effective for CrossFit athletes while imposing less loading and fatigue resulting in better recovery? A new study by a team of German scientists has tested this exact theory(12). Published in the prestigious journal ‘Frontiers in Physiology’, this study examined the effects of traditional HIFT vs. polarized HIFT on a number of key performance parameters in CrossFit athletes.

Thirty experienced, injury-free CrossFit athletes (15 females, and 15 males, average age 26 years), and who were training for at least six hours per week split over at least three sessions per week (remember, HIFT is very demanding!) were recruited. Following baseline testing the athletes were split into two groups, both of which completed a 6-week training intervention. These groups were:

· Polarized HIFT – where the intensity distribution was 78% zone 1 training and 22% training in zones 2/3.

· Traditional LIFT - where the intensity distribution was 26% zone 1 training and 74% training in zones 2/3 (much more representative of most CrossFit athletes’ training distribution).

During the training sessions, the athletes’ heart rates in both groups were monitored by a coach to ensure they remained within the target range. Specifically, the movement tempo, workload, or power was adjusted if the heart rate was too low or too high. The actual training volumes in terms of time duration were matched between the two groups. Before and after the training intervention, the athletes were tested for their performance in the following CrossFit-related tasks:

· Maximal strength in the squat, deadlift, overhead press and, high pull

· Maximal aerobic capacity (VO2peak)

· Lactate threshold

· Peak power output (PPO)

· A benchmark HIFT workout consisting of 1000m rowing, 50 thrusters, and 30 pull-ups, with faster times scoring higher.

What they found

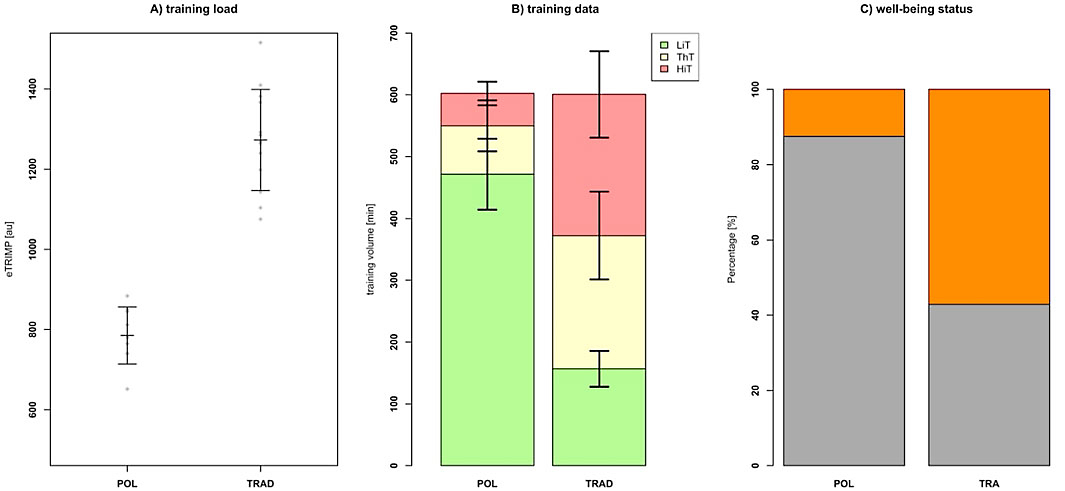

Both groups improved their performances in the deadlift, overhead press, high pull and the benchmark workout test, with the degree of improvement being the same in both groups. However, the really interesting finding was that the athletes in the polarized group achieved these gains while accumulating a far lower training load compared to the traditional LIFT group. Moreover, this was reflected in the comparison of wellbeing status between the polarized and traditional groups. The incidence of poor wellbeing, physical overexertion, or injury was significantly lower in the polarized group than in the traditional group (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Training loads, intensity distributions and wellness

Implications for athletes

This new research shows that a polarized approach to CrossFit training can be particularly beneficial for athletes seeking to maintain high performance levels over extended periods, as it allows for adequate recovery between high-intensity sessions, but does NOT seem to impair training-related performance gains. Even better, athletes who adopt this approach are likely to feel more refreshed, better recovered and to be less injury prone. And while this study was set up to investigate Cross-Fit performance, there’s no reason the findings wouldn’t pertain to athletes who perform other high-intensity conditioning programs such as circuit training.

For those CrossFit athletes who have performed well with traditional HIFT, one way of putting this different approach into action might be to vary HIFT and polarized training; HIFT can be the mainstay of training, but having one week in every three or four where polarized training is adopted, allowing the high-intensity gains to be consolidated while ensuring better recovery and adaptation. This is conjecture of course; we need more research to investigate what the optimum balance might be. But what we can say for now is that taking an easier, polarized approach looks like a great option for athletes who want performance gains in CrossFit without pushing themselves to the limit all the time!

References

1. What is fitness? CrossFit J 2002. 3, 1–11

2. Scand. J. Med. & Sci. Sports 2017. 27 (11), 1258–1262

3. Orthop. J. Sports Med 2016. 4 (8), 2325967116663706

4. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022. 19 (8), 4526

5. J. Sports Sci 2016. 34 (3), 209–223

6. Front. Physiology 2019. 10, 1307

7. J. Appl. Physiology (Bethesda, Md. 1985) 2013. 114 (3), 411–420

8. Eur. J. Sport Sci 2006. 6, 1–14

9. Sports 2023. 11 (2), 24

10. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023. 5, 1258585

11. Front. Physiology 2020. 2 (11), 534688

12. Front Physiol. 2024 Nov 15:15:1446837. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2024.1446837. eCollection 2024

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.