You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Endurance performance: can a short, sharp shock work wonders?

SPB looks at new research suggesting that a short burst of high-intensity intervals added to your training could be just the ticket for performance gains

There’s an old adage that says “If you do what you’ve always done, you’ll get what you’ve always had.” But many endurance athletes employ the same one-pace training day in, day out only to be surprised that they (inevitably) fail to make progress. The problem is that grinding out steady-state, one-pace workouts only tend to produce performance gains in the earlier stages of training – ie in novice athletes. Once the muscles and cardiovascular system have adapted to a steady-state routine, an inevitable performance plateau that one-paced training brings is reached.

More intense option

Once adaptation to a steady-state one-pace training regime has occurred, something different is needed for further performance gains. Increasing the pace of steady state training is of course an option, but the risk is that it leaves the athlete both exhausted and injury-prone. What’s needed is a way of maintaining base endurance but lifting maximal aerobic capacity for those all important races and competitions, and one of the very best ways of achieving this is by incorporating interval sessions in a training program.

As almost every athlete and coach knows, interval training’ is a method of training that intersperses intervals of high-intensity exercise, with short periods of rest. Done right, interval training allows athletes to get larger fitness gains, faster than simply ploughing along endlessly at a steady intensity. Until comparatively recently however many interval sessions recommended by coaches were fairly daunting – for example, 8 x sets of 4 minutes on the bike performed at 90-95% maximum aerobic capacity (hard!) or 6 x 800m on the track at near race pace. Perhaps this explains why comparably few club and recreational athletes incorporated these sessions into their own programs!

Short intense intervals

In the past 10-15 years however, a large body of evidence has accumulated showing that club and recreational athletes can have most of their cake and eat it. This is thanks to the use of sessions of shorter duration, high-intensity intervals, typically employing 8-10 intervals of around 30-60 seconds’ duration often dubbed ‘high-intensity interval training or HIIT for short(1-3).

A number of scientific studies have shown that per unit of time invested, HIIT is very effective at producing the necessary changes in muscle biochemistry for fitness and performance gains than training at a constant, one-speed pace (steady-state training). For example, one study demonstrated that 2.5 hours of sprint interval training produced similar biochemical changes in muscles to 10.5 hours of endurance training and similar endurance performance benefits(4).

Meanwhile, a 2010 study found that performing 7 x 30-second sprint intervals was just as effective at increasing markers of aerobic fitness as 3 x 20-minute hard efforts despite the fact that during the latter, the total work performed was 8 times greater and the exercise duration 17 times longer than during the sprint intervals(5). And just to underline the value of short intervals, a Canadian study found that a HIIT program consisting of sessions consisting of 6 intervals of just 10 seconds sprinting was still able to produce significant gains in measures of aerobic fitness(6)!

A short HIIT shock

There no doubt that compared to steady-state, one-pace training, the addition of HIIT to a training program brings very significant performance benefits. This is not surprising; there’s good evidence that HIIT can improve maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max – one of the best indicators of aerobic fitness) more effectively than doing only traditional, steady-state long aerobic workouts(7-10).

But how effective is the inclusion of HIIT for athletes who are already possess good levels of fitness and who are training using a variety of training intensities to develop even higher fitness levels? Could the addition of short burst HIIT result in additional fitness and performance gains? Specifically, could the addition of a short training segment consisting of 1-2 weeks (often referred to as a ‘microcycle’) of HIIT boost aerobic fitness and lift performance even further?

The evidence is somewhat mixed; adding a short HIIT microcycle has been observed to improve endurance performance-related variables in tennis and soccer players when that HIIT training included more high-intensity work than the control group(11-13). In addition, studies on skiers and cyclists have shown that a HIIT microcycle can produce significant gains in maximum aerobic capacity (VO2max)(14-16).

By contrast however, other studies investigating changes in VO2max after a HIIT microcycle have reported no significant changes compared to control conditions (where the athletes simply continued their normal training)(17,18). But to complicate matters further, remember that VO2max, while very important, is not the only determinant of endurance performance. A key factor is the % of VO2max that athletes can sustain for long periods (ie without significant lactate accumulation in the muscles)(19,20).

As an example, consider athlete A with a VO2 max of 64mls/kg/min who can sustain 95% of VO2 max for long periods. He/she can therefore sustain an oxygen uptake of 0.95 x 64 = 60.8mls/kg/min. Compare that to athlete B with a higher VO2max of 70mls/kg/min but who can sustain only 85% of VO2max. In that case, sustainable oxygen uptake is 0.85 x 70 = 59.9mls/kg/min. In this case, athlete B could be expected to outperform athlete A in a sustained maximal effort event.

New research

Ideally, what is needed is a carefully controlled study that studies the effects of a short HIIT microcycle on already aerobically well trained and fit endurance athletes and compares it with the athletes’ normal training program(s). The good news is that brand new research conducted by Norwegian scientists has done exactly this. Published in the journal ‘Frontiers in Sport and Active Living’, this study compared the physiological and performance effects of a 6-day high-intensity interval (HIIT) block in well trained (VO2max 69.6mls/kg/min) X-country ski athletes with a second equally fit group who spent the same time period doing their regular training(21).

In this study, 24 well-trained male XC skiers were randomly allocated to one of two groups as follows:

- A 6-day HIIT training intervention (12 skiers) - The 6-day HIIT block started with one daily HIIT session during the first three consecutive days, followed by one recovery day, and finally two days in a row with one daily HIT session. All HIIT sessions were similar and performed as indoor roller ski skating on a large treadmill. The HIT sessions were performed as 6 × 5-minute work intervals with varied intensity within the work intervals designed to maximize the time spent about 90% VO2max. Each 5-minute work interval consisted of 3 × 40sec surges at 100% of maximal aerobic speed, interspersed with three 1-minute periods where the velocity was adjusted to that which produced the skier’s second lactate threshold (blood lactate level of 4mmol/L) plus another 20% of the difference between that speed and maximal aerobic speed. In short, this meant that the skiers were still working pretty hard during the rest intervals but not quite as hard as during the 40-second 100% of maximal aerobic speed segments. To reiterate, this research-validated HIIT protocol was specifically designed to maximize time spent above 90% of VO2max and induce maximum endurance gains – see this article for more details of the protocol and how to apply it.

- A control group (12 skiers) - The control group continued their normal training (which also contained some interval training) with no restrictions except for the two days prior to pre- and post-testing being similar to the HIIT skiers to ensure similar recovery status during testing.

Although the two groups differed in that one performed HIIT sessions and the other did not, the overall distribution of endurance training time, categorized into the three-zone intensity model commonly used by endurance athletes (especially those following a polarized training structure – see figure 1 and this article) was very similar, with the athletes’ intensity distributions being very closely matched. In addition, there were no group differences in mean training hours during the month preceding the study and power, plyometrics, and heavy strength training amounts were broadly similar.

Table 1: The 3-zone intensity model

|

Zone |

Sometimes known as: |

Subjective feel: |

Typical blood lactate levels |

Typical heart rate |

|

1 |

‘Aerobic’, ‘easy’, ‘recovery’, ‘long slow distance’ etc |

Easy – you feel like you can keep going and going |

Less than 2mmol per litre (mM/L) |

Under 80% and typically around 70-75% of maximum |

|

2 |

‘Threshold training’, ‘intensive endurance’ etc |

Moderately hard – hard (you know you’ve had a workout) |

Between 2 and 4mmol per litre (mM/L) |

Around 80-85% of maximum |

|

3 |

‘Very high intensity’, ‘race pace’ etc |

Very, very hard (you won’t want to stay in this zone for long!) |

More than 4mmol per litre (mM/L) |

Significantly over 85% of maximum |

The polarized theory of training uses the concept of three ‘intensity zones’ - 1, 2 and 3. Studies on elite athletes such as runners and rowers suggest that the best way of achieving maximum endurance potential is to spend the bulk of training time in zone 1, at least some time in zone 3 but not to spend too much time in zone 2 (the moderately hard zone).

What they tested

Before and after the 6-day intervention, the skiers were assessed for the following parameters:

- Maximum oxygen uptake capacity (VO2max).

- The maximal 1-minute speed attained during testing for VO2max.

- The speed at which blood lactate reached 4mmol/L (ie the point at which exercise transitions from sustainable to unsustainable – this point aligns with the transition from zone 2 to zone 3).

- Blood levels of haemoglobin (to measure oxygen carrying capacity of the blood).

What they found

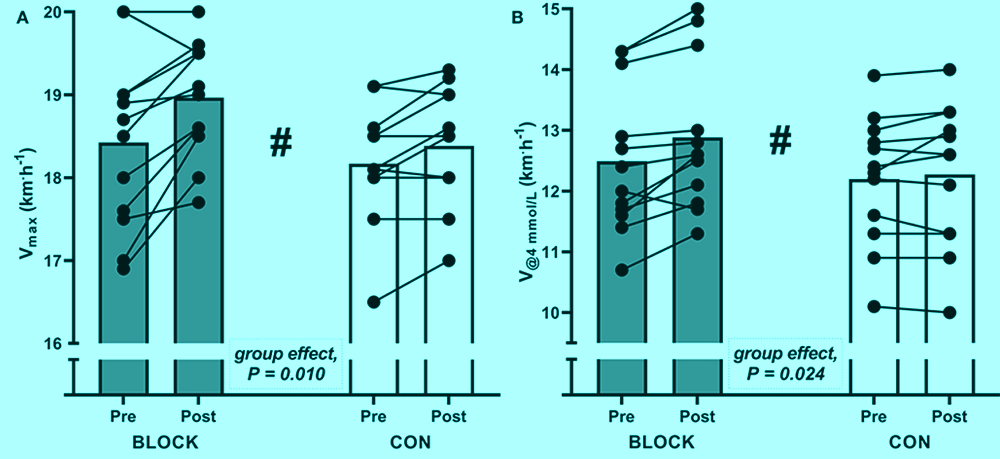

The key findings were as follows (see figure 1):

- The skiers performing HIIT showed a very significantly greater improvement than the controls for maximal 1-min velocity achieved during the VO2max test, with gains of 3.1% vs. 1.2%, respectively.

- The speed at which blood lactate reached 4mmol/L (ie the point at which exercise transitions to becoming unsustainable) rose by 3.2% in the HIIT group compared to 2.1% in the control group. As explained earlier, this is an important measure as it plays a large part in defining what proportion of VO2max can be utilized for sustained periods during a race, and therefore overall performance.

- Both groups increased VO2max slightly but these gains were not significantly different between groups.

- For speeds of 10-12kmh, the HIIT group showed greater economy (efficiency) gains, larger drops in blood lactate and a greater reductions in perceived effort pre to post-training.

Figure 1: Pre/post changes following HIIT or normal training(21)

Related Files

Understanding these findings

These findings are interesting and relevant for endurance athletes because they suggest that a short 6-day burst of HIIT incorporated into a regular training program can produce an extra uplift in performance, over and above that produced by even a very well constructed polarized program. The key benefit seems to be in the ability of athletes to sustain a faster pace near to VO2max, not only at full pelt (ie right at VO2max), but also at second lactate threshold (ie around 90-95% VO2max, which is typically very close to race pace). And while this study didn’t follow up with real-world X-country skiing performance testing, the results fit very well with previous research on elite X-country skiers, where the introduction of short HIIT microcycle produced a clear improvement in the International Ski Federation’s ranking points, indicating improved performance(22).

For athletes wishing to experiment with the addition of an HIIT microcycle to produce an extra lift in performance, there are a couple of caveats. Firstly, the interval structure described above used was very carefully chosen to ensure that the time at or above 90% VO2max in the intervals was maximized. Therefore, this is what would be recommended, and readers can find the details in this SPB article by Andrew Sheaff, as well as in the study details. Simply banging out 30-second intervals at a high intensity with varying rest lengths is not likely to produce any benefits.

Secondly, the benefits produced in this study were observed after a full five days of recovery following the HIIT microcycle. Why five days afterwards? Because it takes that long for the training adaptation and full recovery to occur. Had the testing taken place a day or two after the HIIT block, it’s very likely that the athletes would have actually performed worse. This implies that athlete’s should think carefully about timing of a HIIT microcyle, perhaps aiming to start a block two weeks prior and complete a block around about a week before a key race or event.

Thirdly, bear in mind too that the HIIT microcyle was introduced at a time when the athletes were in a steady period of training, with no extra demands placed upon them, and without the need to recover from recent competition. Adding in an HIIT block during a period of high-load training/competition is not recommended as the total workload could end up tipping the athlete into an overtrained state. With that in mind, athletes should ensure they are well recovered from prior training/competition before experimenting with an HIIT microcyle, paying particular attention not only to physical recovery but also to mental recovery – see this article.

References

- Sports Med. (2002) 32:53–73

- Med Sci Sports Exerc 1997; Volume 29(3), pp 390-395

- Scand J Med Sci Sports. Oct 2009;19(5):687-94

- Journal of Physiology, 2006; 575 (3): 901–911

- Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010 Oct;110(3):597-606

- Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010 Sep;110(1):153-60

- European Journal of Applied Physiology, 2003 89 (3–4): 337–43

- J Strength Conditioning Res, 2007; 21 (1): 188–92

- Med Sc Sports and Exercise, 2007; 39 (4): 665–71

- Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 2007; 10 (1): 27–35

- J Sports Sci Med. (2015) 14:783–91

- J Sport Sci Med. (2014) 13:259–65

- J Strength Cond Res. (2013) 27:1384–93

- Eur J Appl Physiol. (2010) 109:1077–86

- Scand J Med Sci Sports. (2019) 29:1856–65

- Scand J Med Sci Sports. (2014) 24:34–42

- PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:1–14

- Scand JMed Sci Sport. (2016) 26:140–6

- Int J Sports Med. (1998) 19:342–8

- Sports Med. (2000) 29:373–86

- Sports Act. Living, 09 November 2022 doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.948127

- Front Sport Act Living. (2020) 2:1–9

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.