You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Interval training: can dynamic sessions outperform traditional workouts?

New research on interval training suggests that using dynamically changing interval characteristics during a session can result in better fitness outcomes

Over the past three decades, there’s been a huge amount of recent research into using interval training as a method of improving fitness. The reason is simple; a large body of evidence has concluded that regular sessions of interval training can produce significant fitness gains in less time and with less effort than a higher volume of steady-state endurance training(1-4). Even better, the benefits of interval training can be realised by all sportsmen and women – not just elite athletes. Indeed, recreational athletes who introduce intervals to a training schedule stand to gain even more than more advanced level athletes (who will almost certainly already be utilizing interval training in their training programs)(5).The ideal interval formula

Scientists have determined that there are six major factors determining the overall ‘recipe’ for productive interval training(6,7). These are:- Total workload of a session

- Duration of each interval

- Interval intensity

- Recovery duration

- Recovery type (ie active or passive)

- Total interval training time per week

However, nearly all of these studies have been steady state in nature, not dynamic. In plain English, they have investigated interval training sessions using a fixed variable throughout each interval session. So for example, studies on high-intensity intervals have almost always employed sessions where athletes complete a set of intervals at a fixed workload (power, speed, % of maximum power etc) in each and every interval in that session – to find the ‘optimum’ intensity for each interval. But more recently, researchers have begun to question whether a static approach really is best, and instead if a more dynamic approach, where the variable itself varies through the session, could produce better results.

A dynamic approach

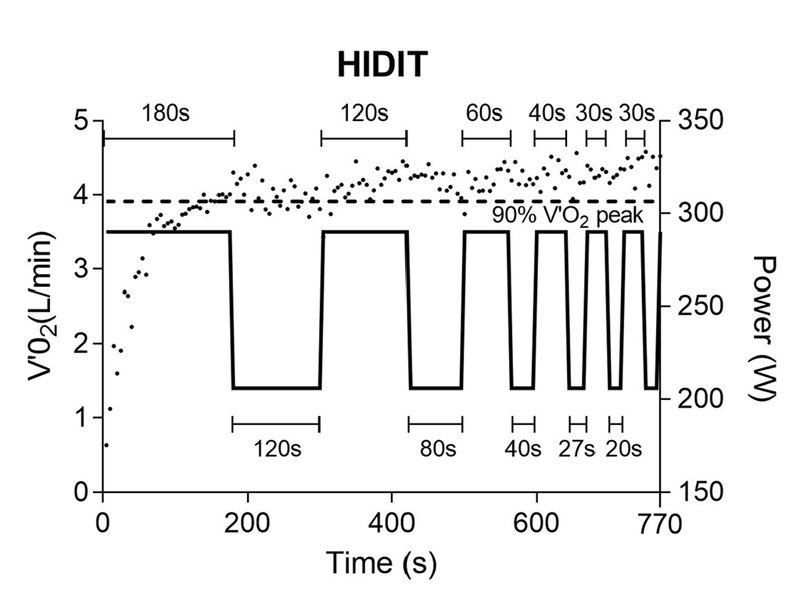

Only last year, we reported on new research using a dynamic approach to interval lengths and durations in an interval session in well-trained cyclists(8) (read this article in full here). In a nutshell, researchers compared a dynamic interval session consisting of ‘high-intensity decreasing intervals’ (work interval lengths starting at 3 minutes duration decreasing to 30 seconds, and recovery starting at 2 minutes reducing to 20 seconds – see figure 1) with a static interval session (one providing exactly the same amount of total workload, and the same ratio of work to recovery but with constant interval lengths and recovery lengths.The results showed that it was the dynamic decreasing interval session that enabled the cyclists to maintain a greater total of time above 90% VO2max (the threshold above which training is deemed to be most effective for boosting endurance). In the dynamic protocol, the cyclists accumulated an average of 312 seconds above 90% VO2max compared to 182 and 179 seconds in the short and long HIIT protocols respectively. In addition, the dynamic protocol also enabled the cyclists to accumulate more total work above critical power.

Figure 1: Dynamic (reducing) interval length/recovery session

The dots represent the breath-by-breath oxygen uptake data averaged every five seconds. The dashed lines represent the threshold of 90% of ̇VO2max (the intensity at which training produces maximal fitness gains). The solid lines represent the actual power outputs of the cyclists during the session.

Brand new research

Evidence for a more dynamic approach to interval sessions has been bolstered by a brand new study carried out by Swiss researchers on runners and cyclists, and which has just been published in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance(9). In this study, the scientists compared the cardiorespiratory responses of a traditional (static) session of high-intensity interval training with that of a session of similar duration and average load, but with a decreasing workload within each bout – ie a dynamic approach.Fifteen well-trained cyclists and 15 well-trained runners each performed two high-demand interval sessions on two separate days. Both sessions consisted of four repeats of 4-minute intervals interspersed with three minutes of active recovery (gentle cycling or jogging in between each interval). However, the two sessions differed:

- In the static (traditional) session, the power output for each of the four intervals was held constant.

- In the dynamic session however, the interval decreased in intensity in each successive interval while ensuring the overall intensity for the four intervals was the same as in the static session.

The findings

The key findings were as follows:- Average oxygen uptake during the interval session was significantly higher in the reducing (dynamic) session for the cyclists (89% vs. 86% of VO2max) However, there was no significant difference for the runners who recorded 91% VO2max during dynamic reducing session and 90% VO2max during the static session.

- The total time spent above 90% of VO2max and the time spent above 90% of peak heart rate was significantly higher for the cyclists when they interval trained using dynamic reducing intervals.

- In both cyclists and runners, average heart rates, pulmonary ventilation (air inhaled/exhaled) and blood lactate concentrations were higher during the dynamic reducing sessions.

Practical implications

Although there’s limited data on this topic, emerging research suggests that for a given total session workload, a more dynamic approach to an interval session (where one of variables in the session is itself varied during the session) produces a higher physiological loading in key aspects of cardiovascular function associated with higher levels of fitness and performance.The $64,000 question of course is whether dynamically structured interval sessions result in significantly larger gains in performance over time compared to static (traditional) session? We don’t have the data to answer that with 100% confidence yet; however, this would almost certainly be expected given the evidence we already have about accumulating time above 90% VO2max(5), so it’s definitely worth a try if you’re someone who likes to experiment. At the very least, a dynamic session provides variety, which can be very welcome in terms of motivation and compliance.

If you’re tempted to try a more dynamic approach in interval sessions, remember that you are not increasing or decreasing the overall workload in an interval session - the total work performed remains the same. So for example, if you want to experiment with interval length or rest length as your session progresses, make sure that your total interval duration remains the same as in your previous sessions, and use a stepwise progression down - likewise for decreasing interval intensities. If you’re a coach considering experimenting with a more dynamic approach, remember that you will need to monitor your athletes’ performances over a period of time to ensure it is working for them – don’t expect all athletes to respond in the same manner!

References

- PLoS One. 2014 Apr 15;9(4):e95025

- Eur J Sport Sci. 2016;16(3):344-9

- J Sci Med Sport 2007; 10: 27–35

- Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008; 294: R966–R974

- Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010; 20 Suppl 2: 1–106.

- Sports Med. 2002, 32, 53–73

- J. Strength Cond. Res. 2007, 21, 188–192

- European Journal of Applied Physiology Aug 2020 doi.org/10.1007/s00421-020-04463-w

- Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2021 Feb 19;1-8

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.