You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Ironman triathlon novices: the art of prediction

How long will your first ever Ironman triathlon take to complete? SPB looks at evidence-based methods to predict your Ironman finish time, which can also help inform your pacing and nutrition requirements

Comprising a back-to-back 2.4-mile swim, a 112-mile bike ride and a full 26.2-mile run, embarking on an Ironman-length triathlon for the first time involves a journey into the unknown, both physically and mentally. Of course, most triathletes relish this challenge; it’s not just the buzz of overcoming physical adversity that such distances create, it’s also great for putting the trivial hassles of daily life firmly into perspective! However, while all competitive athletes like a challenge, too much uncertainty can be very unsettling, especially for would-be Ironman triathlon novices.

One of the biggest uncertainties of all is knowing exactly what you’re letting yourself in for; you know the (long) distance you have to cover but what you don’t know is how long it’s all going to take you. And that’s important because the duration of your event is going to affect both your pacing and your nutritional requirements, particularly in the later stages of the race.

Unfortunately, predicting your first Ironman time is an extremely imprecise science. You might think that you can just take your steady-state training pace for each discipline and extrapolate out from there. However, it’s not as simple as that; the extraordinary length of an Ironman means that you’ll almost certainly be entering new and unknown territory where you’ll encounter new levels of muscular fatigue, severe nutritional challenges and the possibility of cramps, blisters, dehydration etc.

The art of prediction

Because of its severity, the physiological demands of an Ironman triathlon have always fascinated sports scientists. This explains why there have been a number of studies into what makes a good Ironman triathlete, and what characteristics in a given triathlete help predict a fast Ironman time. For example, one study compared the height, weight, and percent body fat data of accomplished Ironman triathletes with those of elite athletes from the sports of swimming, cycling, and running(1). It indicated that the physiques of these elite triathletes were most likely to be similar to that of elite cyclists.

Other studies have shown that (for short-distance triathletes at least), elite triathletes are likely to be tall, of average to light weight, and with low levels of body fat(2). Also, research suggests that body composition – specifically a low level of body fat - is important for an overall fast race time and fast split times in each of the three disciplines(3). Meanwhile, a Swiss study on Ironman and ultra-triathletes (up to double-Ironman length) found that faster performance times were predicted by low levels of body fat in both cases(4). Interestingly, high levels of training volume predicted the best performances in ultra, whereas speed during training predicted the best performing Ironman-length triathletes. In another study published the same year (2015) by the same team of scientists, the most important predictive variables for a fast Ironman race time were an age of 30-35 years, a fast personal best time in Olympic distance triathlon, a fast personal best time in a marathon, high volume and high speed in training (where high volume was more important than high speed) and low body fat(5).

Unanswered question

Of course, while this is all very interesting, none of the above studies were able to answer the question of how a novice triathlete might be able to better predict his or her race time – only whether their particular physical or training characteristics were likely to endow them with the potential to turn in a good time. However, an early study did take a closer look at this question(6). In this study, the researchers studied 83 male recreational triathletes participating in the 2009 Ironman Switzerland race. During the afternoon prior to the race, the researchers took a number of physical measures including height, weight and body mass index (BMI). They also took skinfold measurements to determine body fat percentages.

What was different in this study however was that the triathletes had also been keeping comprehensive training diaries, which recorded data for each training session performed in the run up to the event, including the distance, duration, and average speed of training sessions. This data, along with the personal best times for an Olympic distance triathlon and a marathon run, were also gathered. At the end of the race, the times recorded for each triathlete were matched to the data gathered for that triathlete and the results were number crunched to see which (if any) variables predicted race times.

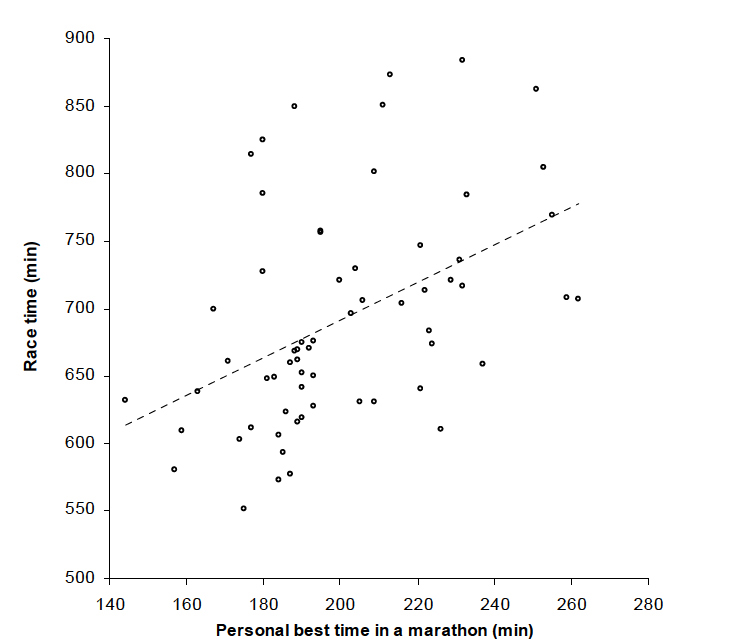

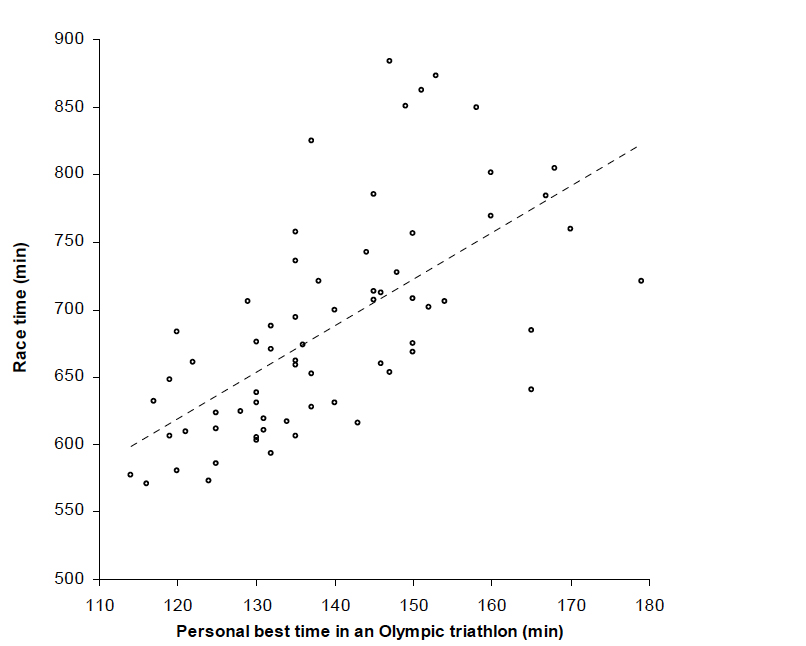

What emerged was that the triathletes’ marathon and Olympic distance triathlon personal best times were strongly related to their Ironman race time (see figures 1 & 2). Also, the average speed when running during training, was related to best times, though less strongly so. In fact statistical analysis indicated that these three variables alone explained 64% of the actual Ironman race time. This somewhat surprised the researchers because they had expected that (in line with previous studies) body fat %, cycling volume, and personal best time in an Olympic distance triathlon would be most related to the Ironman race times.

Figure 1: Marathon performance and Ironman times

Eg, using the best fit line, a 3-hour marathon PB predicts a 670-minute Ironman.

Figure 2: Olympic-distance triathlon performance and Ironman times

Eg, using the ‘best fit’ line, a 150-minute Olympic-distance triathlon PB predicts a 725-minute Ironman.

The best of both

The study above indicates that either previous marathon or Olympic distance triathlon PBs could be useful for predicting your Ironman time. But another study on 53 recreational female triathletes found that it might be possible to combine both of these parameters to yield a more accurate predictive formula(7). As in the study looking at Swiss Ironman Triathlon race data, this study, found that the body characteristics (body composition, height, weight etc) and weekly cycling volumes of the female triathletes were actually quite poorly predictive of Ironman performance. By far the strongest predictors were previous PBs for the marathon and Olympic distance triathlon.

When the data was statistically analyzed for numerical relationships between these parameters, the researchers were able to produce a formula to approximately predict Ironman race times (all times in minutes):

Ironman time prediction (in minutes) = 186.3 + 1.595 × (PB for Olympic distance triathlon) + 1.318 × (PB for marathon)

For example, if a female triathlete has run a 3hrs:30mins marathon and recorded a 3hrs:00mins PB for an Olympic distance triathlon, her predicted Ironman time would be:

186.3 + (1.595x180) + (1.318x210) = 186.3 + 287.1 + 276.78 = 750 minutes = 12.5 hours

Of course, this formula is no guarantee of the actual Ironman time as statistical analysis can only take you so far. Remember too that being derived from a study on female recreational triathletes, this predictive formula may be less accurate when applied to male recreational triathletes.

For male athletes, an independent analysis of data from male Ironman triathlon performances is required, and fortunately, this too is available. The same team who looked at female data carried out an analysis of data on the numerical relationship between Olympic-distance triathlon PBs, marathon PBs and Ironman performance in recreational male triathletes(8). As in the case of the female triathletes, they were able to come up with a predictive formula, which is as follows (all times in minutes):

Ironman time prediction (in minutes) = 152.1 + 1.964 × (PB for Olympic distance triathlon) + 1.332 × (PB for marathon)

Practical implications for triathletes

Getting some kind of handle on a likely finish time for an Ironman triathlon is a potentially useful tool for an athlete making his/her first attempt at this very challenging distance. Not only can it help inform your nutritional and plans for the day and training strategy in the run up to the event, it can also be valuable psychologically, by removing or reducing the uncertainty of challenge ahead. In so many areas of life, knowing exactly the nature of a challenge invariably helps reduce anxiety about how to tackle that challenge, and competitive sport is no different.

If you’re a triathlete planning to compete in your first Ironman event this season, and you’ve already completed an Olympic-distance triathlon and full marathon, using the above formula to gain a very rough idea of your likely finish time is not a bad place to start. However, you need to also bear in mind that Ironman finish time prediction science is imprecise. While these guidelines can give you a rough idea of the time you might achieve, you need to also be prepared for the fact it might take longer. The weather conditions (heat, cold, crosswinds etc), unexpected cramps and blisters, gastric distress, and the fact that we all react differently to physiological stress can all throw a spanner into even the best laid plans! Be aware of the demands on the day and try to plan ahead so that all bases are covered.

It’s also important not to fret or become downbeat if it becomes clear during the race that you won’t make your predicted time. Neither should you rely on previous good performances in the marathon or Olympic distance triathlon to get you through an Ironman. Although they can help predict your first Ironman finish time, you still need to train for an Ironman to get through an Ironman!

References

1. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 1987; 19,45-50

2. Sports Medicine 1996, 22, 8-18.

3. Annals of Human Biology 2000 27, 387-400

4. Open Access J Sports Med. 2015 May 18;6:149-59

5. Open Access J Sports Med. 2015 Aug 25;6:277-90

6. Percept Mot Skills. 2010 Oct;111(2):437-46

7. Chin J Physiol. 2012 Jun 30;55(3):156-62

8. Open Access J Sports Med. 2011 Aug 22;2:121-9

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.