You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Novice athletes: an effective pathway to interval training

How should novice/recreational athletes introduce safe and effective interval training into a program? SPB provides some fundamental guidelines

Studies have shown time and time again that interval training – bursts of harder effort with rest periods in between – is one of the most efficient tools at an athlete’s disposal for building cardiovascular fitness, enabling higher levels of performance to be sustained for longer before fatigue sets in. In the past however, ‘interval training’ has had a bit of an image problem, often being associated with long, grueling and monotonous efforts and only relevant to elite athletes. However, a large body of evidence also shows that novice and recreational athletes, and even completely untrained or metabolically compromised subjects, can also benefit from regular interval training(1-3).While the rationale for utilizing interval training is perfectly understood by many recreational and novice athletes, there’s often a reluctance to introduce it to a program(4). Sometimes this is because old habits (of continuous steady-state training) die hard, sometimes it’s due to concerns about being ‘ready’ to introduce a much more intense training mode, and sometimes it’s simply that athletes don’t know how or where to start. In this article therefore, we will focus on the key elements for a successful and safe introduction to interval training for those with no previous history of this training mode.

Safety first

Before discussing how to integrate interval training into an exercise program, the issue of safety needs to be discussed - particularly for those who are relatively new to vigorous training. By its very nature, interval training requires relatively intense efforts, which places a temporary, higher loading than usual on the cardiovascular system. It’s important therefore to understand the risks involved and how to minimize them to ensure safe and healthy training.Consider these two apparently conflicting truths:

- The best way of lowering your risk of premature death is engage in regular vigorous exercise.

- The risk of death during exercise is greater than the risk of death at rest.

So just how risky is exercise? In an effort to investigate the frequency of exercise-induced death, Dr. Thompson and colleagues collected data on all deaths during jogging in Rhode Island from 1975 to 1980(5). When victims with existing coronary artery disease were excluded, the annual death rate was estimated as 1 per every 15,240 previously healthy joggers. This figure is in agreement with a Seattle study where there was an estimated 1 death per year for every 18,000 physically active men(6).

This rarity of exercise-induced deaths does not justify complacency, however. Dr. Thompson also recommends that any person, whether young or old, who experiences any symptoms during exercise that might possibly be cardiac related, should undergo a full cardiac evaluation prior to returning to training or competition. These symptoms include:

- Chest pain or any other pain that could indicate a heart attack, including pain in the neck and jaw, pain travelling down the arm or pain between the shoulder blades

- Feelings of ‘tightness’ or heaviness in the chest, arm, or below the breastbone

- Extreme breathlessness unrelated to exercise intensity

- A rapid or irregular heartbeat during exercise

- Dizziness

- Fainting

- Nausea or vomiting

This has been confirmed by surveys of studies examining the risks of a cardiac event during exercise testing. For sedentary persons, the risk of suffering a cardiac event during maximal or sub-maximal exercise is 4 in 10,000. However, studies on athletes appear to demonstrate the protective effects of exercise. For example, the German researchers Scherer and Kaltenbach found that in over a third of a million exercise tests carried out on athletes, not a single cardiac event occurred(7)!

Assessing risk

If you’ve ever joined a gym, the first thing you were probably asked to complete was a Physical Readiness Activity Questionnaire (or PARQ for short). Typical questions include whether you suffer chest pains, fainting or dizziness, breathlessness after mild exertion and so on. The main purpose of a PARQ is to identify those with any signs or symptoms of coronary heart disease, because the risks of a cardiac event during exercise are greatly increased when coronary heart disease is present. Those who answer no to all of these questions are usually cleared for exercise.However, while this approach is quick and easy to implement for instructors and trainers, PARQs only give a yes/no answer to whether someone can begin exercise and as such tend to lack subtlety. There’s no indication of the degree of risk that someone faces when they start exercise or up the intensity of exercise. Neither do they provide any recommendations about how any risk affects the way a person should commence an exercise program.

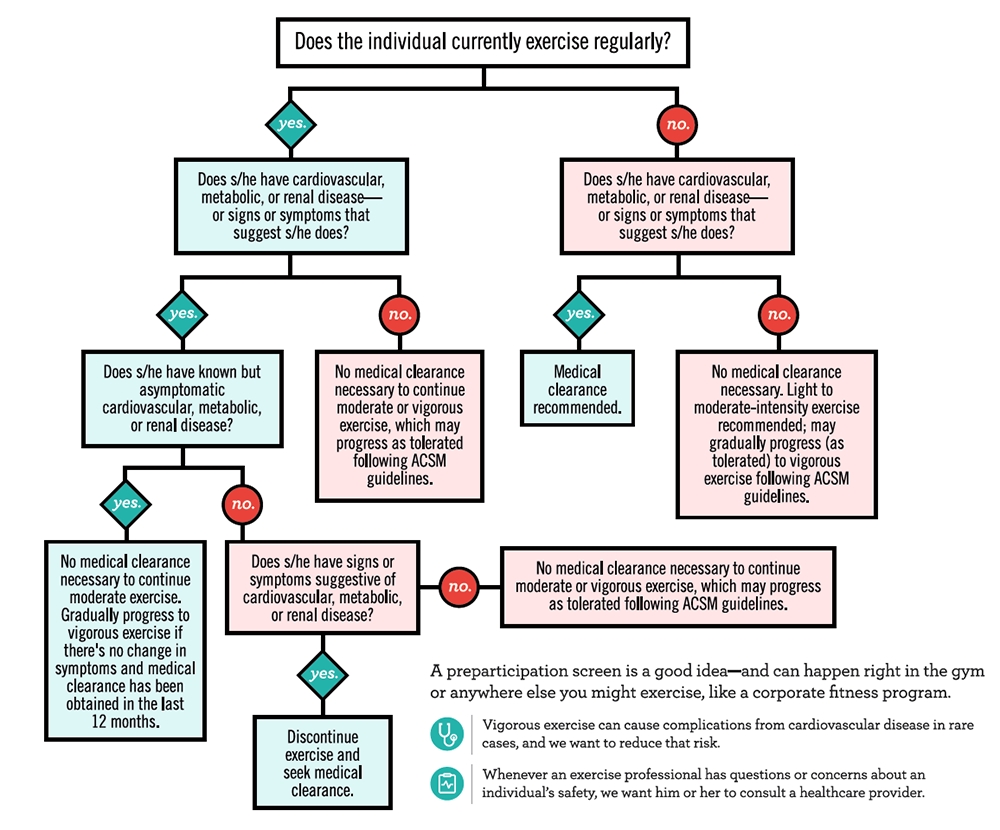

A more subtle, informative and flexible approach is to carry out what’s known as ‘risk stratification’ (in addition to a PARQ). This technique is more nuanced in that instead making blanket recommendations on the basis of yes/no questions, it uses a more systematic evaluation to estimate degree of risk, and therefore if and how a beginner/novice can proceed with intense training. This approach of risk stratification was pioneered by the American College of Sports Medicine and has evolved over time into its current form, which is summed up in the flow chart shown in figure 1 below(8,9).

Figure 1: ACSM Flow chart to establish pathway towards safe introduction of new/more intense exercise

Although the evidence for the benefits of vigorous exercise is overwhelming, novice athletes (especially those over 40) who have never undertaken interval training before or have not been exercising vigorously recently years are strongly recommended to assess their own risk and to determine whether they need to seek medical advice before commencing high-intensity training.

Getting started

Many novice athletes who are relatively new to using intervals are confused about how best to incorporate intervals into their training routine. Questions like ‘How many times per week’’ and ‘Should I use intervals in addition to or instead of my normal routine’? are commonly asked by novice athletes. One thing that’s important to understand is that any interval training you perform has to be seen in the context of any overall training program, rather than in isolation.Without doubt, the biggest risk for those who are already training and who want to add intervals to their program is overtraining and/or injury. That’s because intervals, by their very nature, are relatively high intensity and high-intensity training imposes a higher loading on the body, even when that higher-intensity training is only of short duration. So for example, supposing an athlete wants to increase running performance and is already running three times per week. Adding an extra session in the form of intervals will certainly help performance; however, the increased total training load will require increased recovery while at the same time, there’s less time for recovery - a potential problem.

Overtraining

Building maximum cardiovascular fitness is like walking a tightrope; one the one hand, there’s a need to load the body with enough training stimulus to produce the training adaptations and fitness gains required. On the other hand, athletes need to allow the body enough time to recover in between training sessions – it is after all during recovery that this adaptation occurs. Without enough recovery after a session, athletes are likely to feel tired and even perhaps sore when they next train. Not the end of the world perhaps, but it could mean that the next session is lower quality than intended.A much more serious problem however is when there’s insufficient recovery over a period of many sessions lasting weeks or months. Not only does this increase the risk of injury, it can also lead to ‘overtraining syndrome’, which is characterized by a number of symptoms including(10):

- Feeling washed-out feeling, tired, drained, lack of energy

- Mild leg soreness, general aches and pains

- Pain in muscles and joints

- A noticeable drop in performance

- Insomnia

- Headaches

- Lowered immunity – evidenced by an increased number of coughs, colds and sore throats

- A decrease in your desire and ability to train either long or intensely

- Moodiness and irritability and even depression

- Loss of enthusiasm for the sport

- Decreased appetite

Panel 1: Monitoring recovery

The relatively intense nature of interval training can impose a significant extra loading on the body, which demands sufficient recovery. Fortunately, there are some simple checks to monitor recovery and look for any early signs that you might need to back off a bit in terms of training volume, training intensity or both.- Record your resting heart rate (in beats per minute - bpm) each morning before you get out of bed. You should find that it is fairly constant from day to day. However, if you record any marked increase from the norm, this may indicate that you aren't fully recovered.

- Use a heart rate monitor to record your heart rate bpm during a steady state session at a specific speed or power output. In the short-term, it should remain fairly constant and in the longer term (as your fitness improves), your heart rate should drop. If you notice an increase at any time, this may indicate that you are not getting adequate rest and recovery.

- Another way to monitor recovery to use something called the ‘orthostatic heart rate test’. To perform this, lie down and rest comfortably for 10 minutes the same time each day (morning is best). At the end of 10 minutes, record your heart rate bpm. Then stand up and after 15 seconds, take a second heart rate in beats per minute. After 90 seconds, take a third heart rate in beats per minute and then after 120 seconds, take a fourth heart rate in beats per minute. If you’re well rested, you will have a consistent heart rate between measurements. However, a marked increase (10 beats per minute or more) in the 120 second-post-standing measurement indicates that you have not recovered from previous workouts and that it may be helpful to reduce training or rest an extra day or two before performing another workout.

- Finally, a technique known as ‘heart rate variability’ (HRV) can be extremely useful (see this article for a deeper discussion of HRV). HRV relies on the fact that in a well-recovered person at rest, there’s quite a bit of natural variability in the time interval between each heart beat. However, when recovery is insufficient and fatigue sets in, that natural variability is diminished. Fortunately, modern technology now means that many heart rate monitors can record your HRV and alert you when your recovery is not up to scratch!

Guiding principles

Looking at the essentials of incorporating intervals into a novice/recreational athlete’s training program, we can make a number of practical recommendations using two key guiding principles:- Firstly, it’s essential to allow sufficient recovery when adding intervals to a program – for example by reducing the training load elsewhere. Failure to do so could result in an increased risk of overtraining and/or injury.

- Secondly, because interval training is fairly intense, it’s important to structure the training routine so that athletes are fresh before each session of intervals. If athletes are fatigued or poorly recovered, they might be tempted to skip the interval session or perform them half-heartedly. Let’s see how these work in practice:

For novice athletes new to intervals

- Athletes new to intervals should start by adding no more than one interval session per week and cutting back on an existing non-specific workout elsewhere. For example, an athlete training to complete his/her first half-marathon by building up the mileage on one long run each week should not replace that workout with intervals - but instead replace a less specific session.

- Take a measured approach by starting easy and working gradually into sessions. For example, instead of aiming for 10 x 1 minutes at 90% of maximum effort from the outset, a novice athlete should start with 4 or 5 intervals at 80% effort. Gradually build the number of intervals then build the effort level to 90%.

- Athletes should ensure they schedule a rest day after each interval session, or at the very least, a day where any training load is very light.

- Athletes should also ensure they go into an interval session fresh by scheduling a rest day (or a very light training day) the day before. Never do intervals tired.

- Once a novice athlete has adjusted to performing intervals and is finding them more manageable, he/she should add back in the training session that was initially removed. However, they must continue to apply principles 3 and 4 above.

- Quality is king; rather than try and add a second interval session too soon and becoming fatigued, athletes should ensure they concentrate on performing a really high-quality interval session once a week.

- Monitor recovery. If an athlete feels or monitoring shows fatigue accumulating, he/she should take a week off from intervals completely.

- Complete beginners to exercise should avoid high-intensity intervals completely until they have built at least six month’s worth of base aerobic fitness training.

For athletes already accustomed to some interval training

- Aim for one or two interval sessions per week. However, athletes should adhere to principles #3 and #4 in the section above and space the two sessions as far apart as possible.

- If performing two sessions per week, it is recommended to use two different interval sessions to prevent boredom - while bearing in mind the overall goals (eg targeting the relevant energy systems in the athlete’s particular sport/event).

- Athletes should use a training diary to gauge how different interval sessions are impacting performance – ie to spot positive (or negative) changes in performance 2-3 weeks down the line as a result of implementing a particular type of interval session.

- If athletes are strength training, they should try to ensure that resistance sessions are kept as far apart from intervals as possible (to help ensure maximum recovery). For example, if interval training on a Monday and Thursday, he/she should resistance train on the Saturday.

- Try periodizing interval sessions. For example, the athlete could perform two weeks of 2 x sessions per week followed by two weeks of 1 x session per week. Another option is to block periodize – eg perform intervals two or even three times per week for four weeks then have a complete break for four weeks. The key point is that by varying total workload, the athlete allows the body periods where full recovery and adaptation can take place.

- Athletes should never perform interval sessions into the few days run up to a race or match. This will just sap race-day performance.

- Athletes should always monitor recovery and check for signs of overtraining when undergoing an extended period of interval training, especially if also performing a high load of steady-state training (eg distance cycling, triathlon, swimming, rowing etc).

References

- Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2013;76:51-60

- Front Sports Act Living. 2020 Jun 16;2:68

- Diabetologia. 2020 Aug;63(8):1491-1499

- Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2015 Nov;10(8):1023-8

- JAMA. 1982;247:2535-8.

- N Engl J Med. 1984;311:874-877

- Eur Heart J. 1982 Jun;3(3):199-202

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015 Nov;47(11):2473-9

- www.acsm.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/read-research/acsm-risk-stratification-chart.pdf

- J Athl Train. 2019 Aug; 54(8): 906–914

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.