You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Strength before endurance: should you push the boundary?

SPB looks at new research on rowers, showing how the strength training in a mixed ‘strength plus endurance’ training session impacts subsequent endurance performance

As we have explained in numerous SPB articles, the benefits of regular strength training for endurance athletes are immense. Adding strength training to an endurance program can dramatically improve levels of muscular power and strength, providing an advantage in sprint situations or where good levels of strength and power are also needed in that sport – for example rowing(1).

Even more importantly perhaps, studies on runners and cyclists have shown that the use of lower-body, heavy-weight strength training can improve muscle economy(2). This means that muscles become more efficient, thereby requiring less energy and oxygen to perform, which in turn equates to less fatigue for a given pace. Yet another benefit of strength training is increased muscle and tendon resilience, and a reduced risk of injury(3).

Structuring a strength program

Strength training takes time and energy so it makes sense to strength train in a way that produces the greatest benefits for the lowest reasonable amount of time and effort. In particular, endurance athletes who are training hard for their sport do not have the luxury of performing strength sessions, only to find themselves exhausted and making inconsequential gains!

Many endurance athletes are also time limited; rather than performing separate and additional strength sessions, they will need or prefer to do some strength training as part of a mixed training session that also includes endurance work. This explains why in more recent years, researchers have devoted much attention to investigating the best and most efficient approaches to strength training structure.

What kind of strength training?

In this article, we are going to focus on mixed strength-endurance sessions, but first of all, we need to talk about strength training type. The ‘traditional’ resistance training approach for athletes uses a structure based on a fixed number of repetitions per sets performed at a percentage of the athlete’s ‘1-rep max’ (the highest weight that can be lifted using excellent form and technique for that exercise). – for example, 8 reps per set with the loading set at 80% of 1-rep max. This traditional approach has stood the test of time because it works, even when different percentages of 1RM loadings and reps per set are used(4).

However, an alternative and increasingly popular approach to structuring strength sessions is ‘velocity based training’(5). With a velocity-loss approach, training sets are not performed with a pre-determined number of repetitions. Instead, the velocity loss (ie slowing of the exercise movement during the lifting phase) over the course of a set will determine when the set is finished. Once a certain percentage of the initial speed is lost, the set is over. For example, if the initial reps are performed at 1.0 meters/second and the goal is to limit velocity loss to 20%, the set will continue until the athlete can no longer maintain a minimum velocity of 0.8 meters/second.

Velocity loss is essentially a measure of how much fatigue has been generated over the course of the set. Limiting velocity loss means limiting fatigue during strength training sessions, which enables the quality and the speed of the movement to be maintained. This should in theory have benefits for athletes where the power and speed of the movement is important. For an in-depth discussion on velocity loss training and its potential benefits, readers are directed to this excellent article by Andrew Sheaff.

Strength-endurance workout recipes

Rather than performing a totally separate workout, many endurance athletes who are tight for time perform strength training in a combined session with their endurance training. As for whether strength or endurance training should come first in the session, this was another topic covered by Andrew Sheaff in a recent SPB article. In a nutshell, the research clearly indicates that when improving aerobic endurance is the primary goal, athletes can perform endurance training prior to strength training, or strength training prior to endurance training, without any negative impact on performance(6). However, where strength maximization is also required, performing strength training prior to endurance training gives the best outcome.

High-intensity endurance training

The research above suggesting that prior strength training has no negative effects on endurance performance drew its conclusions by looking at long-term gains in aerobic capacity (maximum oxygen uptake, or VO2max). However, there’s more to endurance performance than just VO2max. What also matters is what % of your VO2max you can sustain for long periods of time (ie when racing), and also how efficiently your muscle can process oxygen to produce movement – so-called ‘muscle economy’(7-9). To develop these aspects of endurance performance requires more intense training, which in turn requires greater muscle strength. So a valid question to ask is whether prior strength training negatively impacts a high-intensity endurance training session? If so, this would mean that athletes might have to rethink how they structure mixed sessions.

New research on rowers

To try and answer this question, a joint team of Chilean and Spanish researchers decided to investigate the prior effects of a prior strength session on 2,000m rowing performance in elite athletes(10). Why 2,000m rowing performance? This is a good event to study because it requires high levels of aerobic and anaerobic power, along with high levels of muscular power/force(11). Just published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, the clever part of this study was that the researchers also looked at the intensity of the prior strength training by having them train at different velocity thresholds (ie different levels of accumulated fatigue. The resistance loading used was also varied to see what impact that had.

Fifteen male competitive rowers aged 15-22 years undertook separate 2,000m rowing time trials under identical conditions on five separate occasions. However, each trial used a different strength training protocols beforehand:

· A set of prone bench pulls (see figure 1) using 60% of 1-repetition maximum (1RM) with a velocity loss in the set of only 10%.

· A set of prone bench pulls using 60% of 1-repetition maximum (1RM) with a velocity loss in the set of 30%.

· A set of prone bench pulls using 80% of 1-repetition maximum (1RM) with a velocity loss in the set of only 10%.

· A set of prone bench pulls using 80% of 1-repetition maximum (1RM) with a velocity loss in the set of 30%.

· No prior strength training (the control condition).

The main outcome was to see what impact prior strength training had on subsequent 2,000m rowing performance, and if there was an impact, whether loading or velocity loss threshold (ie amount of fatigue produced) was the most important factor.

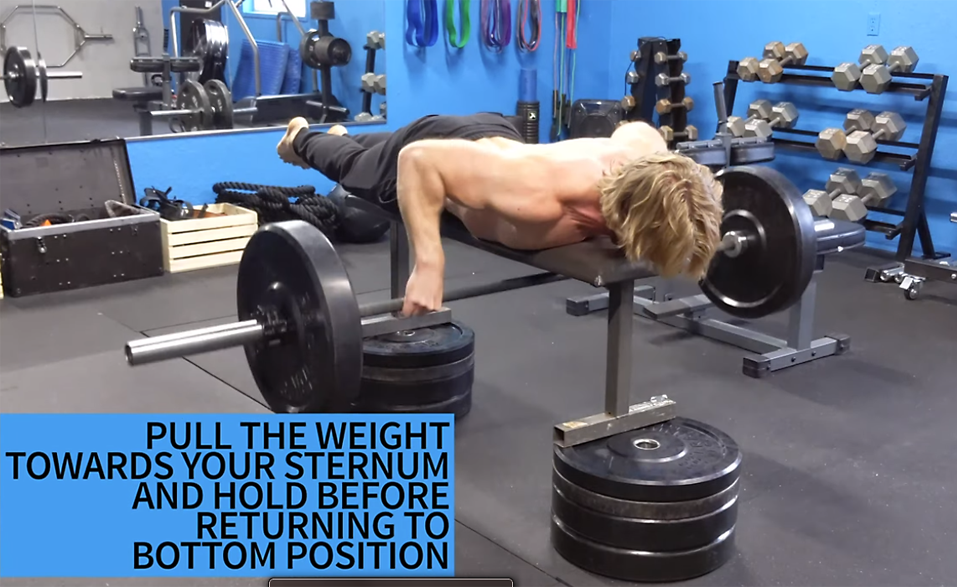

Figure 1: Prone bench pull*

Related Files

While lying face down (prone) on the bench, the barbell is pulled upwards toward the chest, where the movement is paused before slowly returning the barbell to start position. The prone barbell pull targets the rear deltoids of the shoulder along with the biceps and the latimus and upper back muscles. This provides an excellent overlap with the upper body muscles used during the drive phase of rowing. *NB: image courtesy of Buff Dudes Workouts (see their excellent range of exercise tutorials here).

The key findings

The main finding was clear cut: When the rowers performed their 2000m time trials after performing prone bench pulls with 30% velocity loss, their times declined significantly compared to performing no prior strength training. This was the case regardless of whether the rowers had trained at 60% or 80% of their 1-rep max. However, when the velocity loss was limited to only 10% - ie the the set was terminated once the barbell speed dropped below 90% of the speed at the beginning of the set – there was no negative impact on 2,000m performances – again, regardless of rep max loading.

Implications for athletes

What this study shows is that if you are planning a high-intensity endurance session combined with some prior strength training, you need to be cautious about that prior strength training. It seems likely that the loads you lift are not that important, but the level of fatigue you generate within each set is. Terminate your sets with just a small amount of velocity loss and the likelihood is that there will be no negative impact on your subsequent endurance session. Generate too much fatigue by working to higher velocity loss thresholds and you may find your ability to perform an intense endurance session afterwards is compromised.

In practical terms, probably the best recommendation is that when intending to follow up with a high-intensity endurance session (eg intervals), any prior strength training should not be too fatiguing. A velocity loss of 10% is only a slight decline in rep speed; this means you should terminate your sets as soon as you notice any drop in rep speed. It might mean fewer reps but so long as you are achieving 6+ per set, that is enough. Of course, if your subsequent endurance session is a steady-state, relatively low-intensity one, you will have a lot more latitude in how far you push the reps in a set. Having said that, it’s still not recommended to push all the way to failure - but that’s another story!

References

1. Sports Med 2016. 46, 1419–1449

2. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2021 Mar 17;6(1):29

3. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Dec;52(24):1557-15

4. J Strength Cond Res. 2013 Jul;27(7):1791-7

5. Velocity-based training: From theory to application. Strength Cond. J. 2021 43, 31–49

6. Front Physiol. 2023 Jan 26;14:1072679

7. J Physiol. 2008 Jan 1; 586(1):35-44

8. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006 Oct;31(5):530-40

9. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2017; 57(9), 1111–1118

10. J Strength Cond Res. 2024 Jan 1;38(1):e8-e15

11. Front Physiol. 2023 May 30:14:1195641. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2023.1195641. eCollection 2023

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.