You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Strengthening endurance: more class, less mass!

Can endurance athletes gain muscular strength and power without increasing muscle mass? Andrew Sheaff looks at new research

Over the past 50 years, strength training has become accepted as a critical component of the preparation of athletes of all types. This is true of endurance sports, as strength training has consistently been shown to improve endurance performance(1,2). Yet many endurance athletes still hesitate to include resistance exercise in their training programs. One of the main fears that endurance athletes still harbor is that strength training will ‘bulk them up’. This fear reflects an understanding of one of the critical determinants of endurance performance – an athlete’s power to weight ratio.Importance of power-to-weight

The concept of the power-to-weight ratio reflects a simple concept. As endurance racing requires athletes to move their body for long distances over long periods of time, it’s ideal to create as much power as possible, while moving as little bodyweight as possible. Simply put, the more power you can create over time, and the less weight you have to move, the faster you’ll be able to perform. While strength training can definitely enhance the power side of that equation, it can also lead to gains in muscle mass, which could potentially be problematic for the endurance athlete.This trade-off can make the question of whether to include strength training poses a mental roadblock for many endurance athletes. As a result, large numbers of endurance athletes choose to forgo formal strength training, in spite of the documented benefits it brings. Wouldn’t it be nice if endurance athletes could get all of the strength and power benefits of strength training without the potential negative consequences of increased muscle mass? Well, according to new research, it turns out they can!

New findings

The relationship between strength and muscle mass is often thought to be a simple one: an increase in one leads to an increase in the other. However, this is actually quite a contentious point, and the research is far from conclusive. Part of the uncertainty arises due to the impact of nutrition. Several studies have shown that nutritional status – particularly whether or not one is in caloric balance - can impact this relationship. At the same time, these findings are not universal. Depending on whether or not one is in a caloric deficit, it may be possible to improve strength without added muscle mass.To provide some clarity, a group of researchers decided to conduct a meta-analysis (taking a group of studies on this topic and analyzing the accumulated data to look for trends) of studies where strength training was conducted with a caloric deficit(3). These studies were then separated into two groups: a group of studies that also included a control group training without a caloric deficit, and a group of studies that did not include a control group.

The benefit of performing a meta-analysis is that it allows the researchers to pool the subjects across several studies, and then seek to answer the research question with a much larger group of subjects. As the studies were not carried out with the same caloric deficit, the researcher performed a meta-regression, which allowed for conclusions to be drawn about the degree of caloric deficit that impacted the outcomes.

The findings

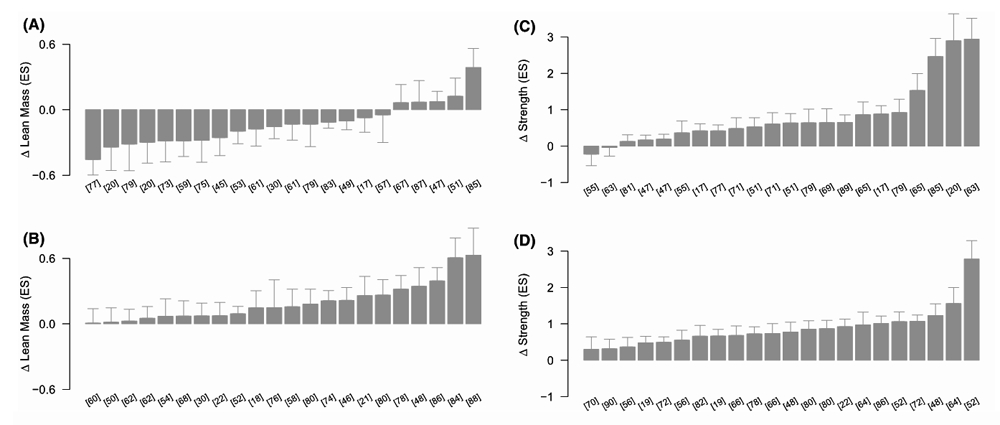

What did they find? Regardless of which studies were used in the analysis, with or without a control group, it was found that a caloric deficit impaired the development of muscle mass in individuals undergoing strength training. Interestingly enough, a mild caloric deficit was not found to impact strength improvements (see figure 1). Furthermore, the researchers found that the caloric deficit large enough to impair strength gains was approximately 500 calories per day.Figure 1: Comparison of strength-training studies with/without a calorie deficit

A and C (top) show lean mass and strength gains when training was conducted with a calorie deficit. B and D (bottom) show lean mass and strength gains when training was conducted without a calorie deficit – ie with ample calorie intake. Note that strength gains were observed in both conditions but that mass gain (B) was much more prevalent when ample calories were consumed.

In plain English, endurance athletes looking to positively impact their power to weight ratio can increase their strength without the negative impact of added muscle mass, provided they maintain a modest calorie deficit of around 500 calories per day (but no more). That’s big news as it provides a strategy that allows for a more nuanced approach to strength training and manipulating the power to weight ratio. Rather than just strength training and hoping you don’t gain weight, or just reducing bodyweight and hoping you don’t lose strength, you can control both aspects at the same time!

Practical applications

Strength training is one of the most powerful tools available to improve your power-to-weight ratio. It universally impacts the power component of the ratio in a positive manner. However, it can negatively impact the weight component when using inappropriately. When aiming to influence the amount of muscle that is gained, it turns out the key dial to manipulate is nutrition, not training.If you need to improve strength, but can’t afford to or don’t want to increase your muscle mass, reducing your calorie intake can help to ensure that you gain the required strength without the accompanying muscle mass. Fortunately, the calorie deficit only needs to be approximately 500 calories per day. Considering that much of this research is performed in individuals who are not carrying out regular endurance training, it’s likely that even smaller calorie deficits would be sufficient to limit muscle mass gains in endurance athletes. When performing the strength training itself, it’s important to note that you should aim to and expect to get stronger, as the evidence clearly shows that it’s possible to gain strength even while in a caloric deficit.

A note of caution

While these strategies can be effective from a performance standpoint, please be aware that long-term, sustained energy deficits can be detrimental to both health and performance(4). Therefore, this should be considered a short-term strategy to accomplish a short-term goal - not a permanent training approach. Likewise, there is no indication that larger caloric deficits will work better. In fact, it’s likely that larger deficits will impair strength gains as well, completely defeating the purpose of implementing strength training in the first place. In addition, a larger sustained deficit could increase the risk of injury and illness. Strive to use the smallest caloric deficit possible.In summary, strength training should be a critical component of the endurance athlete’s training regimen, and is a powerful tool in enhancing power outputs and the power-to-weight ratio. While it is often assumed that strength and muscle mass come as a package deal, this research suggests it doesn’t have to be the case. By manipulating your nutritional approach, as an endurance athlete, you can have your cake and eat it, too!

References

- Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2019 Oct 30;1-13. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2019-0329

- Sports Med. 2014 Jun;44(6):845-65. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0157-y

- Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2022 Jan;32(1):125-137. doi: 10.1111/sms.14075

- Br J Sports Med. 2014 Apr;48(7):491-7. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093502

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.