You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Boost your performance: go play in the peaks!

Altitude training doesn’t have to be costly or complicated. As Rick Lovett explains, just a few days at relatively modest elevations can significantly boost your fitness and race performance…

Before I was a runner, I was a backpacker. So when I talked a friend from my running club into a trek into Utah’s Uintas mountains, keeping in racing shape wasn’t my priority. I made one abortive attempt at trail running then abandoned it in the face of ankle-breaking rocks. In ten days, I ran only twice. When I returned from the mountains (which were around 3000m elevation) to my sea-level home, I initially felt a bit flat. Ten days without much running is a long time. But then an amazing thing happened. In a tempo run, I blew the doors off my 3-mile personal best. Four days later, I destroyed my 10-mile PB in a race, running the 16.1 km distance at nearly as fast a pace as I’d ever managed a 10K. It was an enormous breakthrough.At the time, I simply shrugged and enjoyed the results. Then, twenty years later, I was training to attempt an age graded PB in the 10K. As the race loomed, I developed a sore Achilles tendon and, looking for a way to crosstrain, took a 3-day trek into a nearby wilderness. This time I never got above 1,600 meters. But three days after I came down, I not only met my race goal but beat it by more than a minute.

A few years after that, I again had the same experience, this time in a 5km-run, which I ran immediately after returning from yet another hiking holiday (this one at elevations between 1300 meters and 3400 meters). What I’d discovered anecdotally was that a short stay at even modest elevations seemed to be able to produce a performance boost – a quite different altitude-training formula to the multi-week high-elevation camps favoured by the pros!

More than counting corpuscles

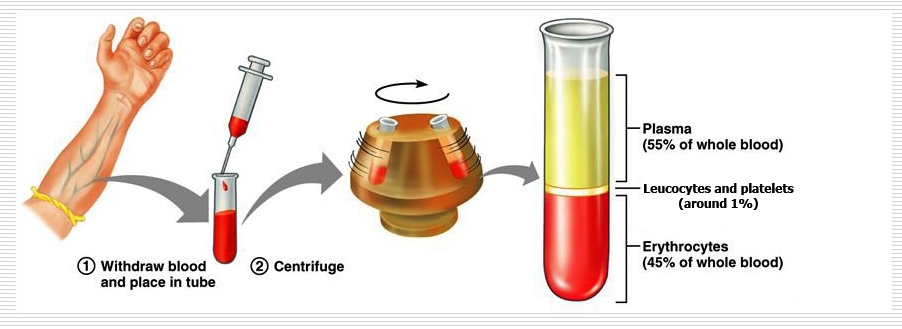

Endurance athletes tend to automatically equate altitude training with improvements in hematocrit: the fraction of the blood made up by red blood cells (see figure 1). But while altitude does indeed stimulate the production of new red blood cells, these cells don’t appear immediately. From start to finish, it takes the body a couple of weeks to produce new blood cells. However, hikers and mountaineers often notice significant adaptations overnight—wheezing when they drive to at 2,500 meters one day, then packing over 3,500-meter passes the next.Figure 1: Blood and haemocrit

CASE STUDY: Ulyana Horodyskyj

Ulyana Horodyskyj (above) is a former research associate and US geophysicist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado. As part of her extensive research on glaciers, Ulyana has spent several years in the Himalayan Mountains. She has also reported improvements on moving to altitude that are too rapid to be explained purely by changes in red blood cell count. As she recalls, “On one occasion after a vacation in Thailand, I recall going from sea level to nearly 16,000 feet (4900 meters) in the Himalaya in 3.5 days. The first day at Lukla (around 9,400 feet), I suffered the effects, and felt quite weak and wobbly. But in just two days I was able to go up to 11,500 feet, and then to 14,000 feet without feeling much at all."

World’s highest ski resort

How is it that many climbers and athletes report such rapid adjustments to and benefits from being at altitude? To find out what might be going on, Robert Roach, a lead investigator at University of Colorado’s Altitude Research Center, organized a study called ‘AltitudeOmics’ —the first ever to look closely at the blood of people trekking up and down mountainsPLoS ONE 2014. 9: e108788.One of the participants was Lauren Earthman, a sophomore at the University of Oregon, Eugene. When she volunteered in 2011, she thought she knew what to expect. Yes, it would be tough, but she was a 1500-meter runner with a 5:03 best, good enough to run for a club that competed against local colleges. But when she climbed out of the bus that carried her to a mountaintop research station in a one-time ski resort in the Bolivian Andes, 5,260 meters above sea level, she got one of the biggest shocks of her life. The bus had been equipped with supplemental oxygen to prevent her and her fellow volunteers from acclimating on the way up. Briefly she felt “sort of okay,” but then she had to walk up a flight of stairs. All of a sudden, her reaction was “Wow, it was so hard – immensely more difficult than I anticipated.” However, less than two weeks later, she and the twenty other study participants were able to run (slowly) up a two-mile hill.

Persistent changes

Since 2011, Roach’s study has produced a dozen publications, including a 2016 report in the Journal of Proteome Research that could revolutionise the way the average runner uses altitude trainingJ. Proteome Res., 2016, 15 (10), pp 3883–3895. This paper seems to confirm that it’s not necessary to wait for the body to produce new red blood cells before you start feeling the benefits of altitude training. Instead, even a few hours in a reduced-oxygen environment is enough to begin unleashing a cascade of changes within existing red blood cells, without the need for the body to make new ones. These changes make it easier for blood cells to carry oxygen to the muscles that need it, and are linked to how haemoglobin in the red blood cells binds oxygen. Moreover, these biochemical changes appear to be permanent for the life of the blood cells.The higher you go and the longer you spend there, the greater these changes are likely to be, but the fact is that a few days hiking or skiing in the Alps, Spain, Morocco, or Central Europe may be all it takes to give you an explosive race performance soon after you return home.

Furthermore, there are strong indications that return visits to altitude are cumulative – so long as they aren’t so far apart that all of the altitude-adapted cells have died off and been replaced. In other words, several short high-elevation holidays might be as effective as one longer one.

Support for this theory comes from veterans of the US Army’s 10th Mountain Division, which earned fame in Italy during World War II. Years ago, many soldiers reported that their bodies had seemed to retain adaptations from repeated trips to high elevation—a finding that tracks the experience of backpackers who return weekend after weekend to the high country.

Legendary coach Bill Bowerman, one of the founders of Nike, appears to have had the same idea. In preparation for the 1967 NCAA Track and Field Championships in Provo, Utah, (elevation 1400 meters) Bowerman took his team to 1700 meters for a total of nine nights’ altitude preparation, says Portland, Oregon, coach Bob Williams, who had been the team’s steeplechaser. But instead of doing it in one stint, Bowerman broke the stay into three separate weekends. And, Williams notes, “Bowerman was 10th Mountain Division!”

Seeking the heights

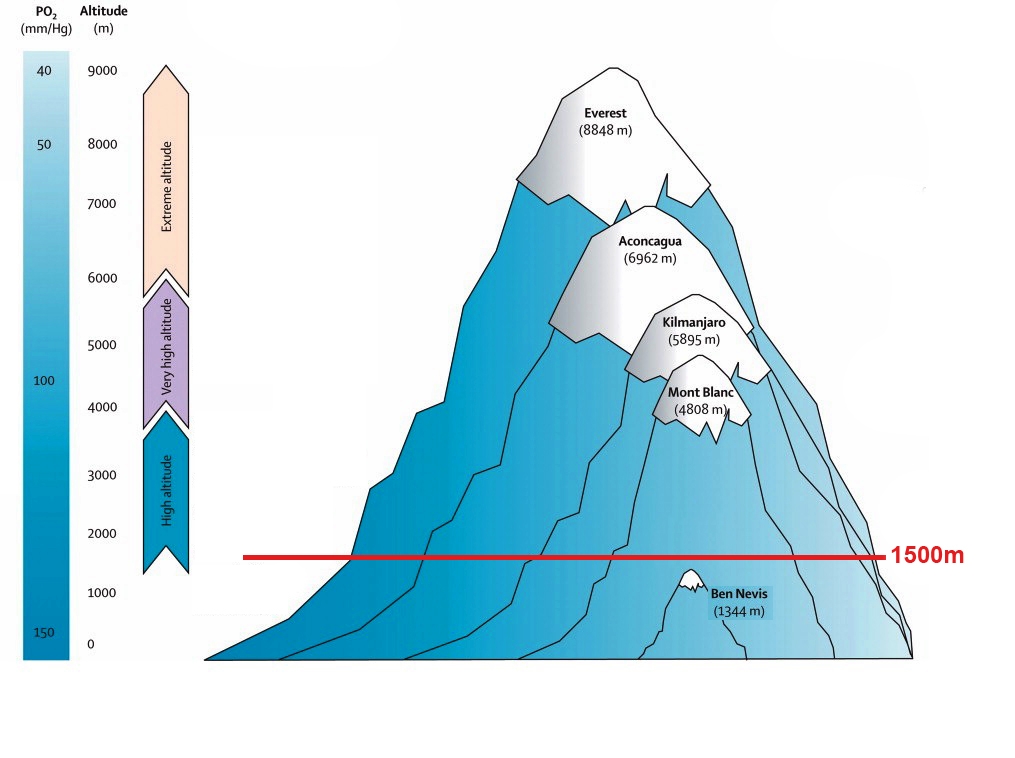

For those living in the UK, taking advantage of this for training does have some practical problems. Unless you want to camp on top of Ben Nevis, it’s difficult to go high enough for long enough to get much of an altitude boost (see figure 2). You’ll probably have to go to the Continent to find a place high enough to suit the purpose. But all that means is that you need to synchronise your holiday schedule to your race plans. So long as the holiday gives you a few nights above 1,500 meters, you’ll probably see a benefit when you return.Figure 2: relative altitudes of different mountains

That said, you still need to keep fit and undertake some training while you’re on holiday. Not that this means you have to obsess over training; if you have the opportunity to practice your primary sport a few times, that’s great. If you can’t, whatever type of cross-training you get from an active vacation will suffice (though if you aren’t practicing your primary sport, you may need to give yourself a week or so to get your body reaccustomed to it when you return). As rule of thumb, this readjustment will probably take about the same length of time as you spent crosstraining at altitude – eg ten days for a ten-day holiday, a week for a shorter one, etc.

CASE STUDY: Lyndy Davis

The first time Oiselle-sponsored marathoner Lyndy Davis (PB 2:42:41) attempted short-term altitude training, it wasn’t intentional. She’d been training for a half-marathon when, four weeks before the race, a friend got married in Park City, Utah, elevation 2,000 meters. Park City is a ski-resort town nearly as far from Davis’s home in Portland, Oregon, as Vienna is from London. She flew out for a long weekend, spent three nights, and ran as much as she could, exploring the local trails.Then, a week before her half-marathon, she took another holiday, this time doing a three-day circuit of Oregon’s Mt. Hood, with much of the time at elevations above 1800 meters. “I wasn’t running,” she says. “I was backpacking.” She came back down on Monday, did four days of easy, taper-style workouts, and came within 6 seconds of breaking her half-marathon PR on a hot day on a hilly, partially gravel, course that was probably about 150 meters over distance.

Three weeks later, she was again at altitude, this time for a three-day family vacation at a lake, 1500 meters above sea level. But this time she ran. “I went on the trip knowing I could keep in training,” she says. When she came back to sea level, she felt tired for the first couple of days. Then, all of a sudden, she was running the best track workouts she’d ever done. “I was faster than I was used to and recovering really, really fast between sets,” she says.

Unfortunately, that time she hadn’t planned a race in which to cash in on the benefits of her altitude training. But come this spring, she intends to spend a few days at a ski lodge, working remotely and training, a week before taking a shot at a fast time in a spring track meet. Lyndy’s advice to others attempting to find a similar formula that might work for them is to read their bodies and learn to feel the timing that works best for them. The first time she went high, she says, “I was frustrated because you come back thinking immediately you’ll feel great. But it was more like recovering, and you get the benefits later.”

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.