You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

High intensity training: reduce or maintain your base volume?

Should endurance athletes reduce or maintain their low-intensity training volume when introducing high-intensity work into a program? As Andrew Sheaff explains, new research on cyclists provides some answers

Since athletes first started competing, they’ve recognized that training must be comprised of several different types of training. You can’t simply repeat the same thing over and over again and expect to improve. There are a variety of different types of training that are effective in improving performance. For endurance athletes, there’s low intensity training, there’s threshold training, and there are all sorts of different high intensity interval training, from short distance repeats to long distance repeats to everything in between - not to mention supplementary training such as strength or flexibility work.

But just as athletes recognize that different types of training have value, they also know (or should know) that these different types of training are best used when organized in a specific manner. Simply performing many different types of training in a random manner doesn’t work nearly as well as when they are performed as part of plan designed to produce a specific performance gain.

Low-intensity volume comes first

One of the most common approaches to organizing endurance training is focused on accumulating a large amount of low intensity training volume at the beginning of a preparation period – ie the emphasis is very much on volume and not on intensity. Then as competitions approach, there is a gradual or sometimes abrupt shift towards more intense training, typically in the form of various types of interval training. At this point, the volume of low intensity training is often reduced to allow for better performance during high intensity training, as well as to allow for better recovery from that training.

However, just because something is traditional or common place, doesn’t mean it’s the most effective strategy. Indeed, quite a few coaches believe in maintaining a relatively consistent volume of low-intensity training when high-intensity work is introduced, which is at odds with the typical approach of dropping the volume of low intensity training during intensified training. The belief is that maintaining a fairly consistent volume of low-intensity training approach will better support the maintenance of certain endurance qualities, leading to more stable and sustainable performance in the longer term.

The evidence

While much research has repeatedly demonstrated that a focus on high intensity training, at the expense of low intensity, can lead to substantial improvements in performance, it is often pointed out that these studies are short-term in nature. It’s not that they don’t work - it’s just not clear what happens after these shorter training blocks, or how stable performance is in the longer term. This is one of the main reasons some coaches favor the maintenance of low intensity training because they believe it allows for more stable performance over longer periods of time.

The question is, do these coaches have a valid point? Are they right that maintaining low-intensity volume during higher-intensity training periods produces additional benefits in the longer term? To date, there is simply no research to examine what happens when low intensity training volume is maintained during high intensity training blocks so it’s been impossible to say whether the training adaptations might be greater or lead to potentially positive benefits. However, some new research has provided a valuable insight into this question and useful answers for coaches and athletes.

New research

In this study, a team of Danish researchers decided to compared these two approaches to see the results(1). Particularly interesting was the fact that this study tested competitive cyclists during their competitive training – ie it was the real deal! The researchers took 18 highly trained, elite cyclists and had them perform high-intensity interval training three times per week for six weeks, using both 4-minute intervals and 30-second intervals. All subjects performed the same interval training. What differed between groups was the amount of low intensity training that was performed:

- One group maintained their low intensity training volume.

- The other group reduced the amount of low intensity training by about 33% (which equated to about five hours less training per week).

Before and after the training period, the subjects were tested with ‘400-calorie’ time trials – ie how long it took them to expend 400 calories of energy. This time-trial test was performed in two different situations: 1) within a 2-hour ride, which included periodic sprints to mimic a road race, or 2) without the 2-hour ride. During these trials, subjects were evaluated for blood lactate and power output. Metabolic enzymes were also assessed before and after the intervention.

What they found

From a big picture perspective, the results demonstrated (no one’s surprise), that the intensified training period worked. Both groups improved performance in the 400-calorie trial, with no difference between the groups. However, neither group improved performance when time trial followed the 2-hour ride. While the end results where the same, there were however some interesting findings, demonstrating that the interventions were having different effects.

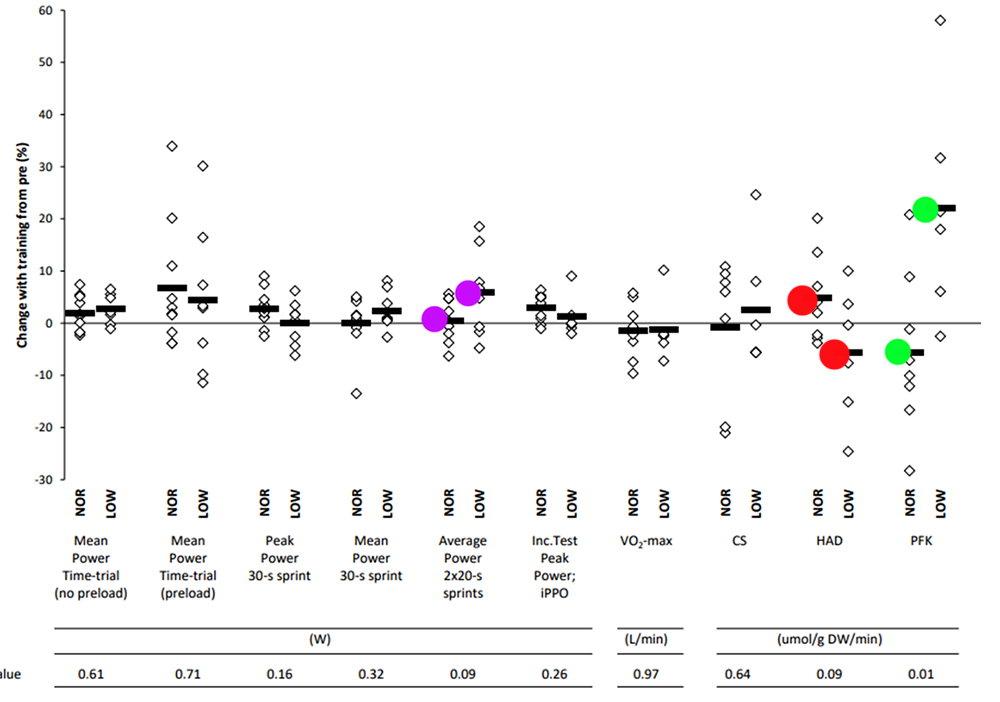

The average power in the repeated sprints during the 2-hour ride improved in the lower volume group, but not in the higher volume group (see figure 1). However, the ability to maintain power throughout the 2-hour ride during the sprints was improved in both groups. Interestingly, the lower volume group demonstrated a significantly higher activity of PFK, a key enzyme involved in anaerobic metabolism. In contrast, blood lactate levels were lower in the group that maintained low intensity volume during the 2-hour ride (indicating a superior aerobic profile).

Thus, it appears that lowering the volume of low intensity work when introducing high-intensity work may shift metabolic fitness towards a more ‘anaerobic’ profile, whereas maintaining the volume of low intensity work may shift metabolic fitness towards a more ‘aerobic’ profile. Over time, and with repeated interventions, this could lead to differences in performances, and larger differences in performance profiles. This shift isn’t good or bad, it would just depend on the athletes goals.

Figure 1: Changes in power output and enzyme levels

NOR = maintained low-intensity training; LOW = reduced intensity training. Each column refers to a different outcome measured. In the purple dot column, the reduced low-intensity training volume group performed better in the average power sprint tests. The also had better levels of an anaerobic enzyme (PFK – green dots). Meanwhile, the maintained low-intensity training volume group had better levels of enzyme markers associated with aerobic performance (red dots).

Practical applications for endurance athletes

So what should you do? Well, that depends! It depends on what your goals are and what you want to accomplish. Fortunately, once you’re clear on your goals determining what to do is pretty straightforward. Lowering the volume of low intensity training when performing high-intensity training seemed to favor improvements in power-based traits, as evidenced by the increases in power during the sprints, as well as elevated anaerobic enzymes. In contrast, maintaining low intensity volume resulted in lower lactate levels, which may signify enhanced aerobic metabolism.

The biggest point is that while there may not have been obvious differences in performance between the two groups there may be long-term consequences of the different approaches that accumulate over a period of time. If your goals are more speed and power based, it probably makes sense to drop the low intensity volume during intensified training. However, if your long-term goals are continued maximization of aerobic fitness, it may make sense to continue to maintain low intensity volume. It’s not right or wrong, just what suits you best!

It’s also a powerful tool to make adjustments in your training. If you need to improve your power more than your aerobic endurance, drop the low intensity training. If the opposite is true, keep the low intensity training up. Rather than a ‘right or wrong’ approach, consider these options as one more strategy that can provide you with a way to fine tune your performance!

Reference

1. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2023 Apr 1. doi: 10.1111/sms.14362. Online ahead of print

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.