You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Interval training: watch your form if you make it intense!

Can interval training session adversely affect stride patterns and biomechanics, and if so, how can these effects be minimized? SPB looks at new research

Over the past twenty years ago, dozens and dozens of studies – many of which we have reported in SPB - have demonstrated the very significant benefits of interval training for developing aerobic and anaerobic fitness in a wide range of athletes and sports [Follow this link for an overview of some of this research]. But while much has been written about the precise benefits of interval training sessions, how to construct effective interval sessions and how to integrate them into an existing training regime, relatively little research has been carried out on how interval session might affect an athlete’s movement patterns, either during interval efforts themselves, or in the longer term.

Running gait matters for economy

Good form when running is central not just to the sport of running, but so many other sports where running is a key part of that sport (eg soccer, rugby, basketball hockey etc). A runner’s movement patterns during running (known as form or more correctly ‘gait’, and which includes parameters such as stride length, pelvic tilt, vertical displacement, type of foot strike, ankle pronation etc) really do matter.

The first reason is that a biomechanically efficient running gait means that runners can move efficiently across the ground without wasting energy(1). This results in good running economy, which means that less energy is required to maintain a given submaximal speed compared to a runner with poorer economy. And that matters as studies have shown that having good running economy is an extremely important factor for determining performance, at both elite and recreational levels of competition(2-5).

As an example of this, running gait and stride patterns are known to significantly affect the peak impact forces experienced by runners during footstrike (see figure 1 below). It turns out that there’s a link between peak impact forces and running economy; lower peak impacts forces in runners have been strongly and significantly correlated with more efficient movement and improved running economy(6). This is likely as a result of the lower vertical displacements (bobbing up and down movements) that are observed with an efficient running gait, which will help reduce impact forces upon footstrike.

Running gait and injury

A second reason to think about running gait is injury – or more precisely, injury prevention. Although no two running gaits are identical, when running gaits deviate excessively from the norm, or become too asymmetrical, injury risk is increased, which also explains why gait retraining programs can be successful at reducing the risk of injury in runners(7).

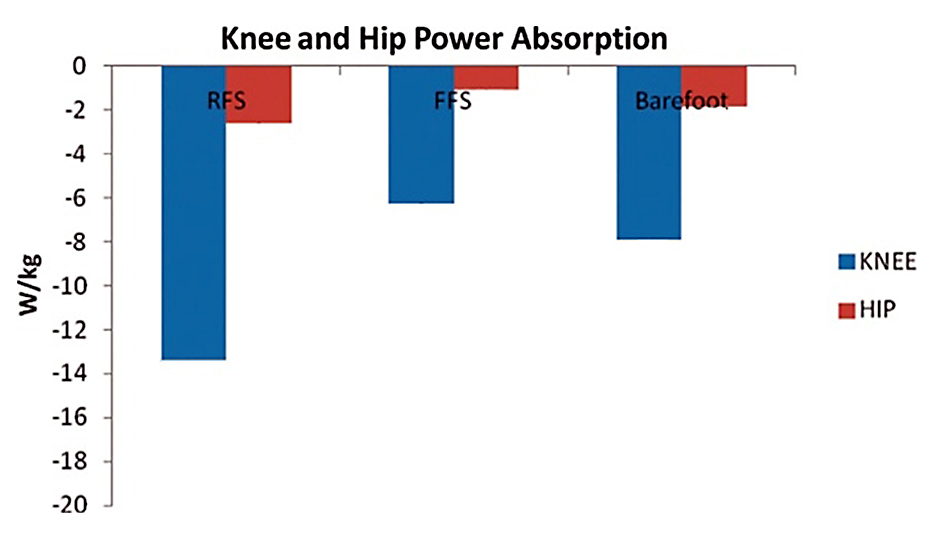

As an example of how running gait/style can influence the risk of injury, consider that peak impact forces during footstrike are known to be an important factor for the risk of lower-limb injuries in runners (higher impact forces are correlated with an increased risk of injury)(8). Now let’s look at data from a study that compared two quite different running gaits: forefoot and rearfoot striking(9). You can see in figure 1 that the impact forces that the knees and hips of runners had to absorb were much higher when a rearfoot strike pattern was used compared to a forefoot strike pattern (and also when barefoot running, which encourages a forefoot strike pattern). Of course, this doesn’t mean that all rearfoot strikers are injury prone and all forefoot strikers are not – far from it. But what it does show is that running gaits and styles can play a role in determining injury risk.

Figure 1: Power (impact) absorption differences between rear foot, forefoot and barefoot running

RFS = rear foot strike; FFS = forefoot strike; Barefoot = barefoot running. Barefoot and forefoot runners demonstrated increased plantarflexion (toes pointing downwards) at initial ground contact, which decreased the peak impact forces that were experienced at the knees and hips.

Interval and running gait

Getting back to our original question, can interval training sessions affect running gait and if so, what are the implications for runners? To date, there’s been little research on this topic and the research that has been carried out has been contradictory - most likely because of the very large number of variables in interval training sessions (interval number, length, intensity, rest type and length etc). Also, these studies typically only looked at gait patterns during interval training as a additional parameter rather than as the main focus of the study itself(10).

However, a brand new study by Spanish researchers has attempted to definitively answer this question(11). Published in the journal ‘Gait & Posture’, this study consisted of a systematic review, drawing together all the previous research on this topic, followed by analysis to look for robust evidence on if and how interval training affects running gait. A systematic search on various scientific databases was carried out for studies on running gait and interval training. After analyzing 655 possible studies for inclusion, these were whittled down to nine studies that met all the inclusion criteria:

· Participants were experienced runners.

· The training sessions performed included interval training.

· The studies evaluated the acute (immediate/short-term) effects of the interval sessions.

· The studies evaluated kinematics (movement patterns) as one of the outcome measures.

Only two of these studies measured kinematics changes during interval bouts, while the other seven measured how the kinematics of the runners changed from pre to post-interval session. However, all of the nine studies were scored as ‘good quality’, allowing the researchers to draw robust conclusions.

What they found

The key findings were as follows:

· The type of interval session performed affected the outcome.

· During shorter, high-intensity interval training sessions (intervals of 200m to 1,000m), running kinematics changed over time with an increase in stride frequency, contact time and vertical displacement of the runners’ center of mass (ie more bobbing up and down).

· During longer intervals (1,000m or more), there were no significant changes in running kinematics.

· High levels of muscle fatigue were induced in the shorter intervals and (perhaps unsurprisingly) this was thought to be the main driver of altered kinematics.

When summing up their findings, the authors suggested that when performing anaerobic and short aerobic interval sessions (200-1000m), runners should include long recovery periods (in the region of 2-3 minutes) to help maintain good form and avoid the increase of stride frequency, contact time and vertical oscillation of the center of mass that inevitably results from muscle fatigue. However, when performing long aerobic interval sessions (over 1000m), a shorter recovery time of 1-2 minutes between bouts is sufficient to maintain form.

Implications for runners

What do these findings mean for runners? The main conclusion we can draw is that when performing higher intensity (faster) intervals, you are much more likely to suffer a loss of form as the interval session progresses compared to performing longer, slower intervals. These findings of form loss over sub-1000m distance intervals are also consistent with recent research on masters runners performing 800m intervals with a 1:1 work to rest ratio (ie not quite meeting the rest requirements outlined above)(12). When moderate-intensity, steady-state running gaits were analyzed before and after a set of 6 x 800m intervals, hip kinematics, coordination, muscle strength, and neuromuscular function were all negatively impacted due to fatigue after the intervals were performed. Moreover, these negative impacts were still present after 24 hours of rest and recovery, potentially placing them at an increased risk of injury.

A loss of running form/gait is undesirable; not only does it reduce your running efficiency during higher-intensity efforts (possibly setting up ingrained patterns in the longer term), the increases in vertical displacement may indicate an increased risk of injury in runners who perform these interval types regularly. To counteract this tendency (of form loss), taking longer rest intervals of at least two and perhaps nearer three minutes is definitely advised. For longer interval lengths at lower intensities, form and gait patterns seem to remain much more consistent, even with short rest intervals of only one to two minutes.

How will you know if your running gait is adversely affected and you begin to lose form during an interval session? The simple answer is fatigue. As soon as you begin to feel muscular (rather than just cardiovascular) fatigue, you can assume that your running form is suffering, even if it seems unaffected to you. If or when that happens, it’s time to extend your rest periods in between your efforts or call it quits for the session. Be aware too that after strenuous interval workouts, your running form might not be quite up to scratch the next day, so try to take it easy!

References

1. J Strength Cond Res. 2019 Jul;33(7):1921-1928

2. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1991 Sep; 31(3):345-50

3. J Physiol. 2008 Jan 1; 586(1):35-44

4. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006 Oct;31(5):530-40

5. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2017; 57(9), 1111–1118

6. J Strength Cond Res. 2011 Jan;25(1):117-23

7. J Clin Med. 2022 Nov 1;11(21):6497

8. Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2015 Nov;105(6):532-40

9. Int J Sports Phys Therapy 2012; Vol 7(5) 525-532

10. J Strength Cond Res. 2016 Apr;30(4):1059-66

11. Gait Posture. 2023 Apr 13;103:19-26. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2023.04.009. Online ahead of print

12. Front Sports Act Living. 2022 Jun 2;4:830278

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.